Montana’s expansion of Medicaid to adults with incomes less than 138% of the federal poverty level has provided health care coverage to 95,000 Montanans. Proposals to take health care coverage away from people who do not meet strict requirements to work a specific number of hours each month (and then report on that work) could hinder access to health care for thousands of these newly-covered individuals, many of whom are working or are unable to work. Arkansas is the first state to take coverage away from people who do not meet a work and reporting requirement, and it has already seen thousands of people lose their health care. While these burdensome requirements especially endanger coverage for those with significant barriers to work, they also can harm young children, rural Montanans, individuals with disabilities, many American Indians, and penalize people who are already working.

Instead of putting measures in place that take away health insurance at a time when someone most needs it, Montana has the opportunity to bolster its successful HELP-Link workforce training program, which has reached over 25,000 Montanans and helped to improve access to targeted workforce assistance.

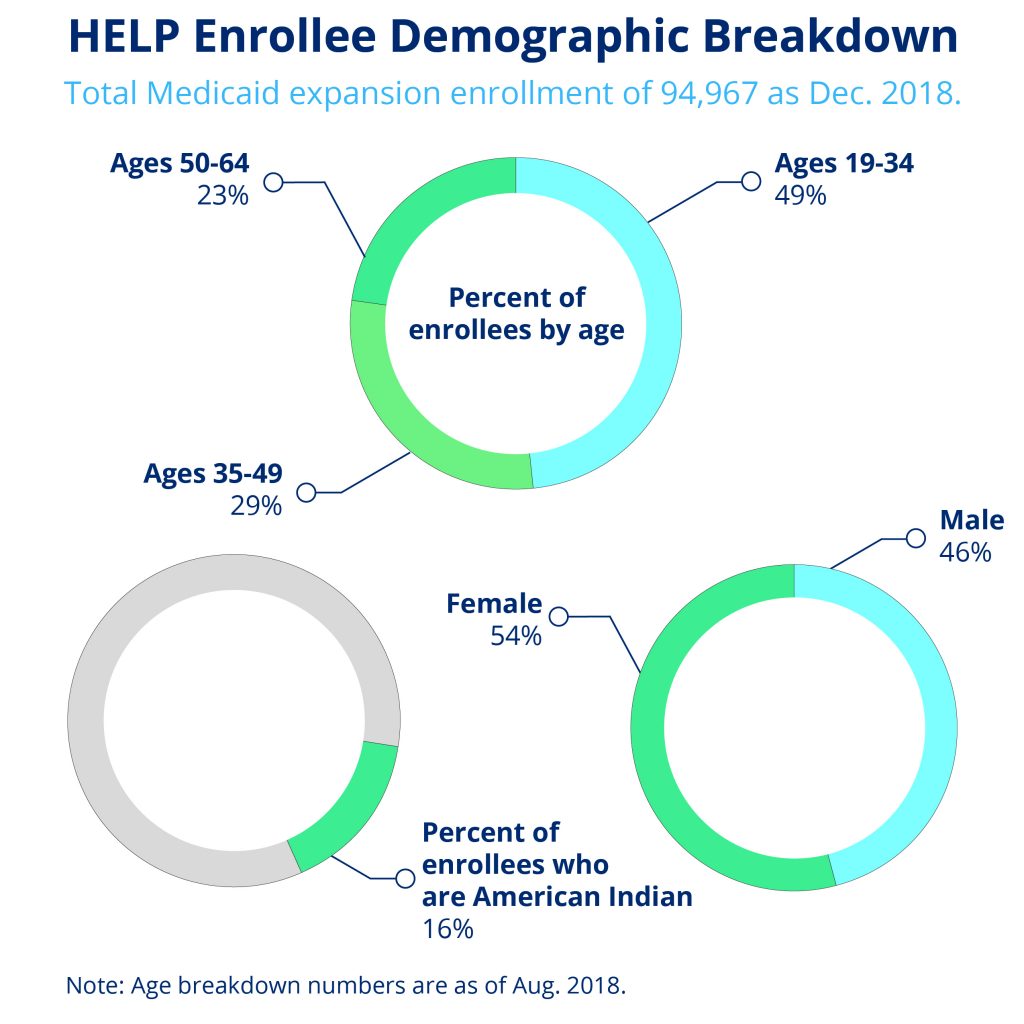

Montana’s expansion of Medicaid, the Health and Economic Livelihood Partnership (HELP) program, has had many economic, health, and employment benefits for the state and its participants. While expansion covers individuals with incomes under 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL), nine out of ten enrollees are living below poverty. As of December 2018, 95,000 adults were enrolled in the HELP program and, to date, 90,000 enrolled Montanans have accessed preventative health care services.[1]

In addition to improving access to health care for Montanans living with low-incomes, HELP has brought the state significant economic benefits, including $58 million in state budget savings and $47 million in new tax revenue.[2] Additionally, the program created 5,000 new jobs and generated $270 million in new personal income for Montanans across the state. The HELP-Link program has helped thousands of Montanans secure employment, and workforce participation has increased among Montanans living on low-incomes. HELP has also transformed access to health care for many American Indians. Medicaid supports Indian Health Service (IHS) and tribal facilities by paying 100 percent of the costs of care for American Indians who are enrolled in Medicaid and receive care at these facilities. That helps ensure that IHS and tribal facilities have the resources needed to maintain and increase their capacity to provide care.

Montana already has an innovative solution to help people on Medicaid gain access to stable employment. The HELP-Link program has connected 25,244 people who are enrolled in Medicaid to Department of Labor and Industry (DLI) employment services.[3] HELP-Link provides intensive one-on-one support that has helped over 3,000 receive employment training services.[4]

Unlike work requirements, which mostly monitor the hours of people who are already working and take coverage away from those who do not, HELP-Link is a workforce promotion program focused on those that need training and assistance. These services include job seeker workshops, assistance for training in high-demand sectors, credit history counseling, and on-the-job-training programs. The program also connects people to other services such as home health aides, childcare, and housing. By addressing actual barriers to work, HELP-Link has been effective at raising employment as well as earnings.

The results for participants have been significant. Of the 3,150 Medicaid clients that completed the DLI workforce training programs in 2016, 70 percent were employed after finishing their training.

Over half of those employed had higher wages after completing the program, with an $8,057 wage gain over the previous year.[5]

Medicaid expansion and the HELP-Link program may have significantly raised employment rates among Montanans living on low-incomes, according to the Bureau of Business and Economic Research at the University of Montana.[6] For Montanans with disabilities living below poverty, there was a 6 percentage-point increase in labor force participation between 2015 and 2016. For Montanans without disabilities, there was a 9 percentage-point increase. Other states did not see similar employment gains during the same period, nor did Montana see similar employment gains among those with higher income levels.[7]

Because Montana has already been able to significantly increase labor force participation among Montanans living on low-incomes, enacting burdensome and expensive work requirements would only distract from Medicaid’s goal of providing health care coverage to individuals who need it. Work requirements ignore the reasons people are not in the labor force, whereas the HELP-Link program helps them overcome these barriers and is a national model for other states looking at ways to help Medicaid enrollees improve employment opportunities.

Proposals to take health care coverage away from people who do not meet stringent work and reporting requirements jeopardize the successes of Medicaid expansion. This could be especially true in rural Montana and Indian Country, where Medicaid has been an important source of health care coverage to communities facing high barriers to care and unemployment rates. As of 2017, almost half (48 percent) of Medicaid expansion enrollees resided outside of Montana’s seven largest urban areas.[8]

Arkansas was the first state to implement a federal Medicaid waiver requiring enrollees meet monthly work and reporting requirements. To date, nearly 17,000 Arkansans have lost health insurance, and the state continues to face serious difficulties administering the burdensome requirements (see case study).[9]

Acknowledging the detrimental impacts these harsh requirements have on access to health care coverage, courts have stepped in to block some states from implementing work requirements. In June, a federal judge stopped a Kentucky plan to introduce requirements that would have caused 95,000 individuals to lose Medicaid coverage.[10] Further, in recognition of the significant loss of coverage in Arkansas, the Medicaid and CHIP Payment Access Commission (MACPAC) sent an unprecedented letter to the Trump administration to reconsider approving any other states’ requirements until the federal Department of Health and Human Services can adequately evaluate and monitor the effects.[11]

Withholding health care from people with significant barriers to work exacerbates the issues that Medicaid expansion has been successful in addressing. As has been the case in Arkansas, many individuals who are trying to work are often kicked off health insurance at a time when they most need it. In many instances, individuals are unaware of the requirements, whether an exemption applies, or how to maneuver the complex filing requirements to verify work or an exemption.[12] Losing Medicaid coverage could lead to gaps in health care for individuals, then making it increasingly difficult to gain or maintain steady employment for those with chronic health conditions. With the gains that Montana has made in expanding coverage to more residents, harmful penalties would move us in the wrong direction.

As work requirements push people off of Medicaid coverage, health care providers – especially rural hospitals and IHS and tribal facilities – likewise suffer. Medicaid expansion has brought $11.7 million in Medicaid revenue for community health centers, and providers have seen a 49% decrease in uncompensated care.[13] With fewer Montanans enrolled in Medicaid, providers would once again be forced to pick up the tab for uncompensated care. This shift would endanger rural hospitals already facing declining populations, high poverty rates, and low levels of private insurance.[14] The same is true for IHS and tribal facilities. Making it harder for American Indians to enroll in and maintain Medicaid coverage would reduce federal funds for the IHS and tribal facilities that provide care to American Indians. That could force them to cut their capacity to treat patients, even as the share of American Indians lacking health insurance and other options for care remains high. The head of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Tribal Technical Advisory committee has warned that “without supplemental Medicaid resources, the Indian health system will not survive.”[15]

Arkansas became the first state in the nation to impose work requirements on Medicaid beneficiaries. While Arkansas’s work requirements have not yet been fully implemented, nearly 17,000 people have already lost their health insurance since the state began applying the policy to adults aged 30-49 in June 2018. Even more beneficiaries are likely to lose coverage when the policy is extended to those aged 19 to 29 in January 2019. Arkansas requires individuals subject to the requirements to report on their work activities monthly through a complex online portal. While the state put in place a series of exemptions, many enrollees struggle to understand how to apply for an exemption or how often to report their exemption (each exemption varies). Nearly 22 percent of all beneficiaries subject to the new policy have lost coverage so far - significantly higher than the 6 to 17 percent coverage loss that Kaiser Family Foundation researchers forecasted could result from implementing work requirements nationwide. Confusion over the new system, a lack of awareness, or difficulty accessing internet caused difficulty in complying with the reporting requirements. Without health insurance, many Arkansans face unmet physical and mental health care needs, and providers are again left with uncompensated care costs.

In October, 10,768 Arkansas Works beneficiaries were required to report that they work, engage in job training or volunteer for at least 80 hours a month to comply with the new work requirement policy. Among those who needed to document their work activities in October, only 1,428 people were able to report satisfying this requirement. An additional 914 enrollees newly filed for exemptions.

Out of the remaining 8,426 beneficiaries, only 118 people reported some activities but not enough to satisfy the 80 hours per month requirement. This could mean that many people who did not report and satisfy the requirement did not know about the new regulations or were unable to create accounts and navigate the online portal.

For people who are looking for work but unable to find any, the new requirement is especially difficult. Beneficiaries can only count 39 hours of combined job search and job search training towards their 80-hour requirement. The exemption for attending school is also limited, putting many people striving to improve their workforce readiness at risk of losing health care coverage.

Even if work requirements could somehow avoid unintended consequences, they would still do harm. Specifically among those who are not working and do not qualify for exemptions, as many face major barriers to work and have serious health needs.

Source: Arkansas Department of Human Services

Not only do work requirements hinder Medicaid’s goal of expanding health care access, they are also unsuccessful at achieving the stated goals of increasing work or decreasing poverty. When work requirements have been imposed, research shows that employment increases were modest and faded over time. Stable employment among beneficiaries subject to requirements was the exception, not the norm, and most enrollees with significant barriers to employment never found work.[16]

The vast majority of Medicaid beneficiaries who can work, do work. Out of those who are not employed, virtually all are facing either health-related barriers to employment or labor-force barriers.[17] In fact, in recognition of insufficient employment opportunities, the Department of Public Health and Human Services waived certain work requirements for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program for 33 counties and six of the seven reservations in Montana.[18]

A Brookings Institute analysis of 2013-2014 Census Bureau survey data found that for Medicaid enrollees aged 18-49 with no dependents under age six, only 1.1 percent do not work because they are not interested in working. For those aged 50-64, only 1.4 percent are not interested in working for pay. For those who are actively participating in the labor force yet not working for pay, the most common reasons cited are work-related (e.g. cannot find a job, recently laid off). For those who are not actively participating in the labor force, the most common reasons cited are health or disability related. Health or disability reasons are cited significantly more among Americans aged 50-64.[19]

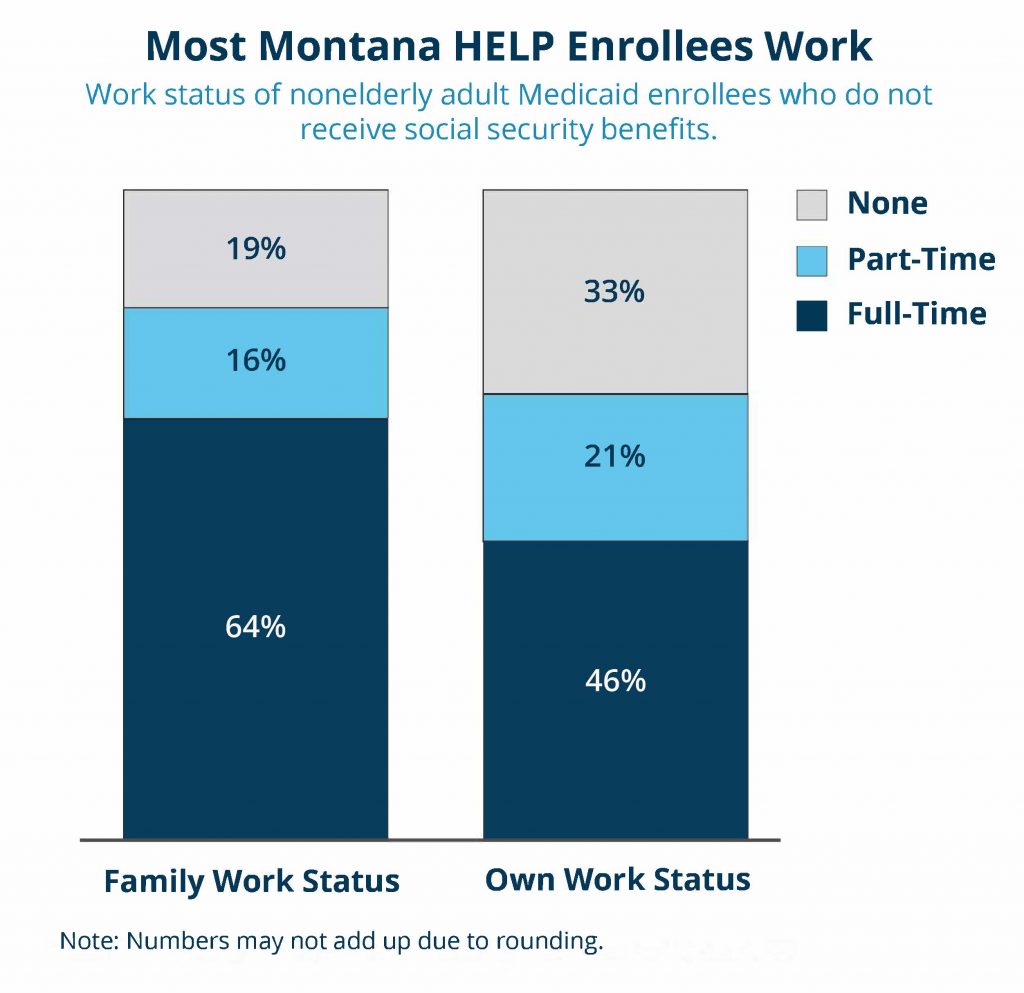

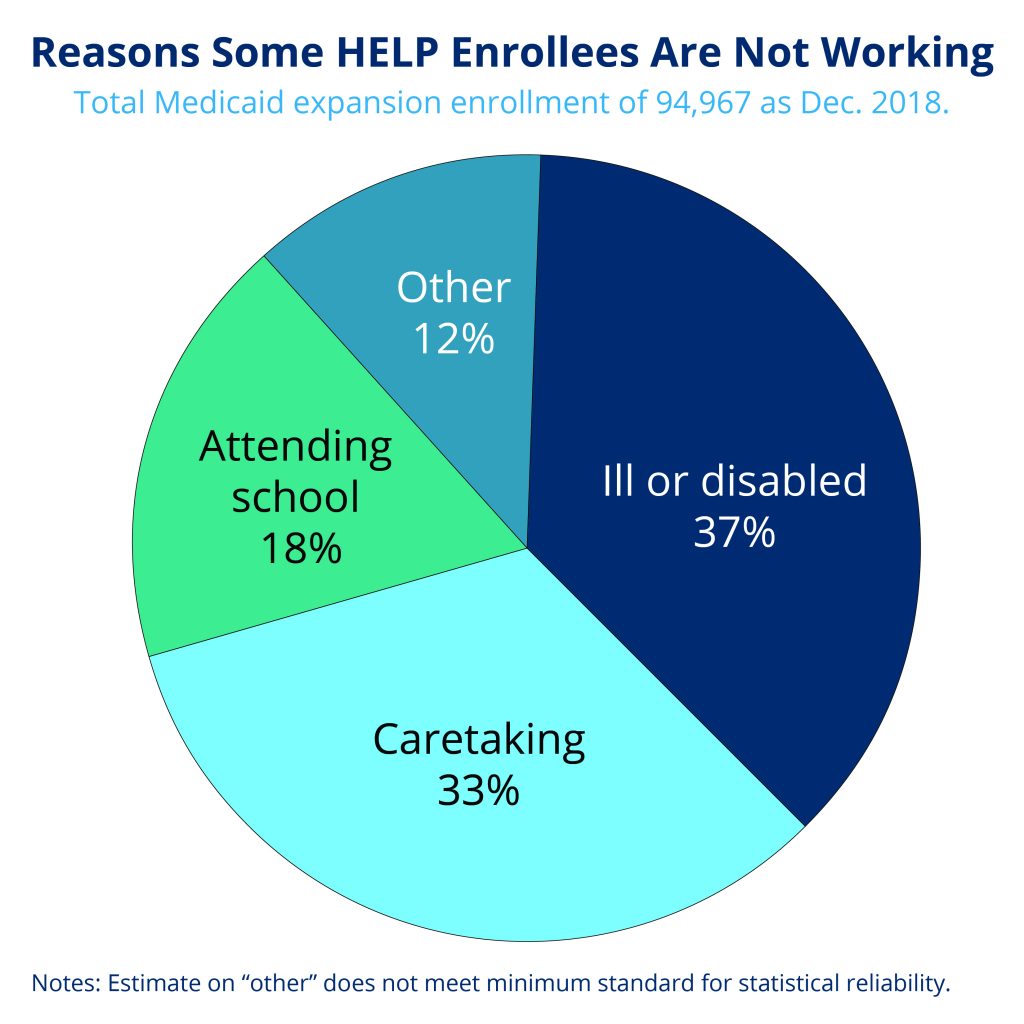

In Montana, the vast majority of Medicaid enrollees already work. Two-thirds of all non-elderly adult Medicaid enrollees work.[20] Only one in five live in a household with no worker present. Of those not working in Montana, 37 percent are ill or disabled, 33 percent are caretaking, and 18 percent are attending school.[21]

Montana HELP Plan participants fill out a survey upon enrollment about their employment situation and barriers to employment. The most common reasons for not working cited were personal finances/credit history and felony/misdemeanor convictions (see Table 1). Proposals to push people off of health care who are unable to meet monthly requirements do nothing to address these barriers to work.

Rather than using state resources to help people access work, these requirements waste taxpayer money tracking hours people are already working. Montana allocated just $885,500 for HELP-Link’s outreach, trainings, and linkages to other services in FY19. In contrast, Kentucky planned to spend $187 million in FY19 to implement its reporting program.[22]

Frequent reporting is also more difficult for rural program beneficiaries. Montana ranks 50th in the nation for access to broadband internet.[23] A lack of internet connection could mean working individuals lose their health care coverage if they are unable to report their hours worked on time even if they have worked enough to qualify for coverage. With two-thirds of non-elderly adult Medicaid enrollees in Montana already working, for the majority of enrollees, work requirements would only create additional demands without increasing their employment.

| Barriers to Employment | ||||

| Help-Link Participants | Help-Link Survey Completers | |||

| Total | % of Total Identifying Barriers | Total | % of Total Identifying Barriers | |

| Personal finances/credit history | 226 | 16.9 | 1471 | 26.3 |

| Felony/misdemeanor conviction | 168 | 12.6 | 1265 | 22.6 |

| Lack of transportation | 130 | 9.7 | 1139 | 20.4 |

| Poor physical health | 113 | 8.4 | 778 | 13.9 |

| mental illness | 88 | 6.6 | 655 | 11.7 |

| physical disability | 85 | 6.4 | 532 | 9.5 |

| lack of childcare | 75 | 5.6 | 810 | 14.5 |

| lack of housing | 69 | 5.2 | 585 | 10.5 |

| lack of telephone | 57 | 4.3 | 554 | 9.9 |

| caring for a family member with health issues | 51 | 3.8 | 483 | 8.6 |

| learning disability | 47 | 3.5 | 320 | 5.7 |

| probation | 37 | 2.8 | 346 | 6.2 |

| drug or alcohol addiction | 35 | 2.6 | 264 | 4.7 |

| domestic violence | 26 | 1.9 | 193 | 3.5 |

| court mandated programs or classes | 16 | 1.2 | 150 | 2.7 |

| pending felony/misdemeanor | 8 | 0.6 | 139 | 2.5 |

| Number Identifying at Least One Barrier | 1,338 | 45.1 | 5,593 | 45.6 |

| Total | 2,968 | 12,270 | ||

Source: Montana Department of Labor and Industry

Not only do monthly reporting requirements fail to increase workforce participation, they also create additional challenges for those who cannot work and those who are already working but in part-time jobs with volatile work schedules.

Monthly reporting requirements fail to accurately reflect workforce participation. In a one-month snapshot of the general population, 20 percent of the population is either out of the labor force or unemployed, according to research by the Hamilton Project. But over a two-year period, 90 percent of the population has been employed at some point. Many workers regularly cycle in and out of employment, and this is especially true for people who are working in low-income jobs. In a given month, 39 percent of Medicaid enrollees are not working. Over two years, however, that number drops by ten percentage points, to 29 percent of Medicaid beneficiaries who are not working.[24] A single month with an unexpected illness, reduced hours, or loss of a job could mean a worker in a low-wage job loses their health care coverage as well.

Workers with low-incomes are especially subject to the volatility of the labor market.[25] Out of those employed, 22 percent of Medicaid participants worked over 20 hours in at least one month within a two-year time span but did not do so in other months, the research showed. This volatility is especially common in rural areas where jobs like farming, manufacturing, and retail commonly feature variable hours, involuntary part-time work, and irregular scheduling.[26] Nearly half (48 percent) of Medicaid expansion enrollees reside outside of Montana’s seven largest urban areas, making it more difficult for them to find work.[27]

Many hardworking Montanans who work in vital Montana industries like agriculture, construction, and health care could lose their health care coverage if they fail to meet the set hourly requirements one month. One in five Montana Medicaid enrollees work part-time and could be subject to losing coverage.[28] Nearly half (48 percent) of Medicaid enrollees in Montana work in the agriculture or service industry, namely construction. Twenty percent work in education or health, fields with many part-time and variable hours.[29]

Older Montanans will encounter additional obstacles. Older workers often face barriers maintaining steady employment due to health conditions that make it difficult to consistently meet hourly work requirements. Age discrimination also makes it more difficult for older people to find new employment or maintain their current position.

Taking away health care would only make it more difficult for people who want to increase the number of hours they work. A survey of Medicaid beneficiaries in Ohio and Michigan found that one-half to two-thirds of respondents said that having health care coverage made it easier for them to look for work, made it easier to work, or made them better at their jobs.[30] Rural Montanans who are often facing greater physical and mental health challenges would be especially hard hit.[31]

Montana’s HELP-Link is already successful at connecting people with health care and jobs. Instituting new, harsh requirements would only serve to jeopardize this success.

Because most people on Medicaid who can work do work, proposals to take health care away from people not working a set number of hours each month do not encourage workforce participation. Instead, they only serve to increase barriers to health care, and in turn, make it more difficult for program participants to maintain steady employment.

MBPC is a nonprofit organization focused on providing credible and timely research and analysis on budget, tax, and economic issues that impact low- and moderate-income Montana families.