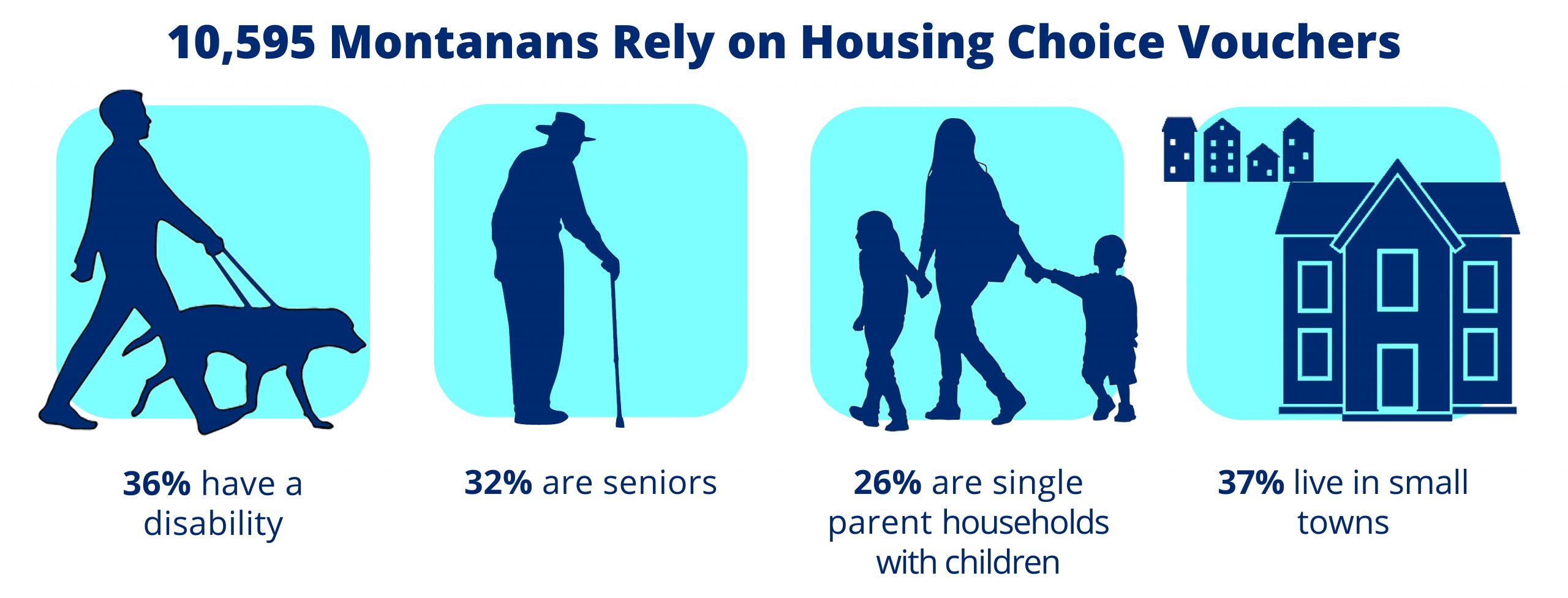

Living in a safe, stable, and affordable home— defined as costing no more than 30 percent of a household’s income— is foundational to individual and public health. The Housing Choice Voucher (HCV) program is the nation’s major housing rental assistance program helping families living on poverty-level incomes, seniors, and those living with disabilities afford their homes. Housing vouchers are shown to lift people out of poverty, improve long-term outcomes for families and children, and reduce racial inequality. Today, housing vouchers support 10,595 Montanans—equivalent to the entire population of Carbon County— in households across the state.[1]

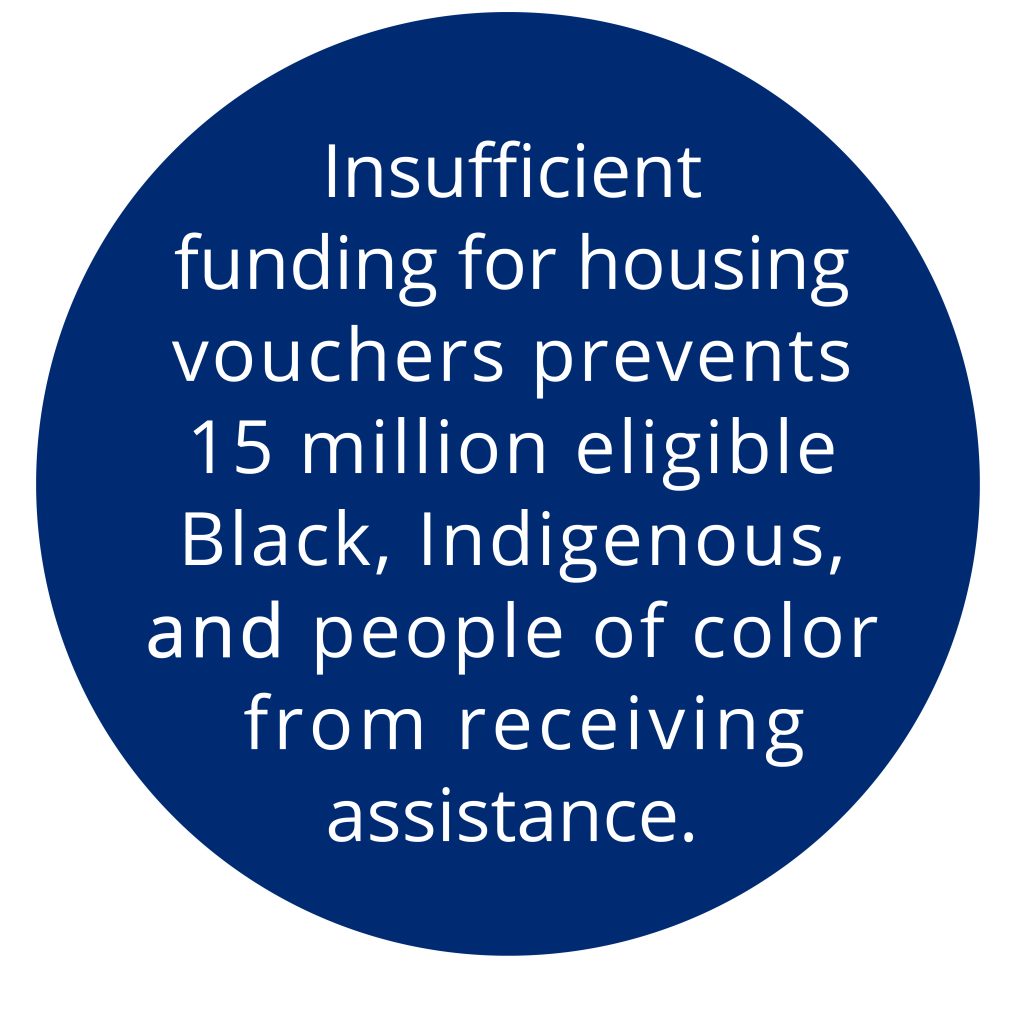

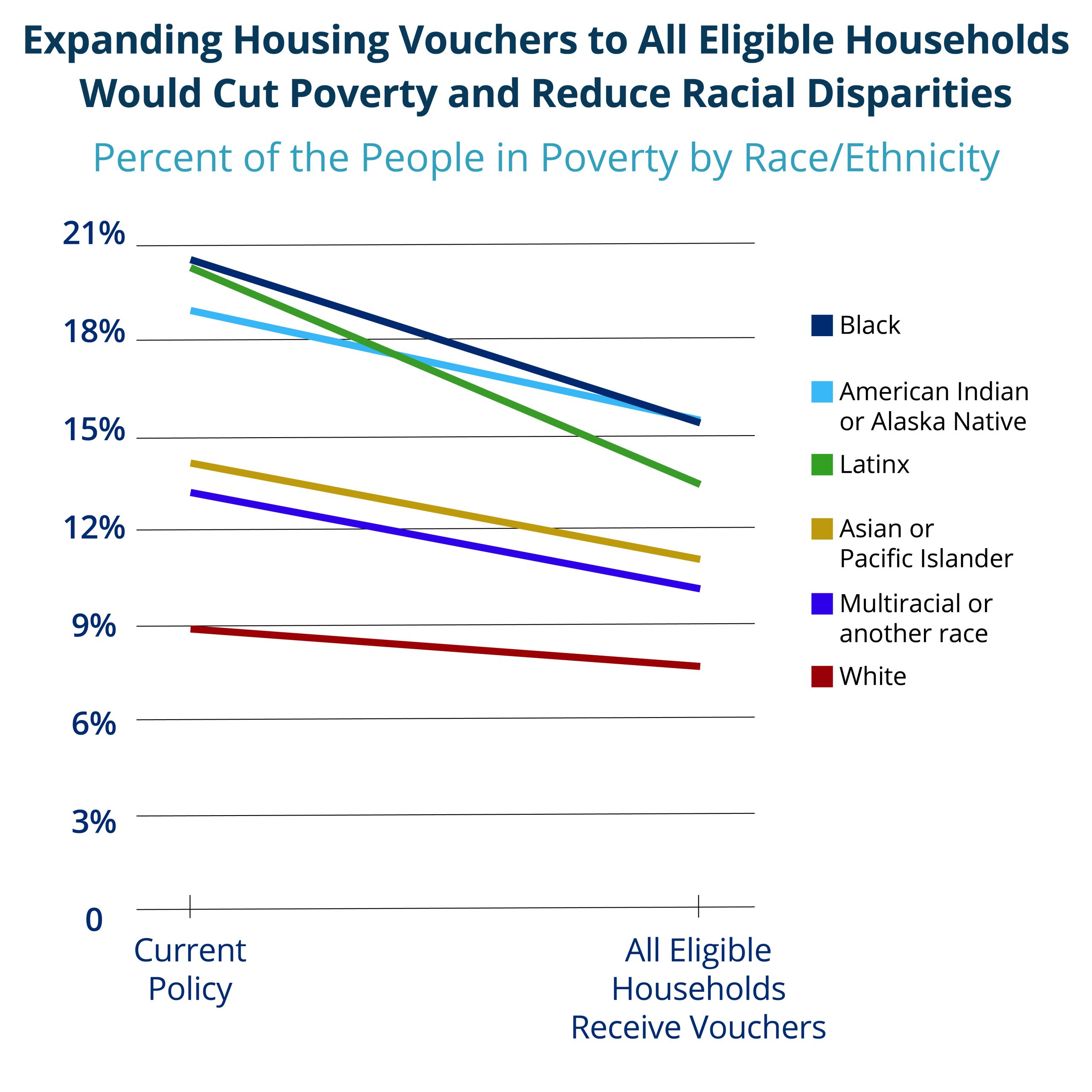

Due to insufficient funding, only one in four eligible households receives housing voucher assistance.[2] Chronic underinvestment in federal rental assistance programs prevents 15 million Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) eligible for assistance from receiving it.[3] Expanding the HCV program would be an essential step towards reducing housing instability for households living on the lowest incomes and correcting our nation’s deep racial inequities.

Background

Millions of households living on low incomes must pay too high shares of that income on housing costs. Of the total 10.8 million renter households nationwide with extremely low-incomes, 70 percent— 7.6 million households— face severe housing cost burden, paying more than half of their incomes for housing.[4] Due to a long history and ongoing practice of racism and discrimination that limits economic and housing opportunities for communities of color, housing challenges, such as severe housing cost burdens, overcrowding, evictions, and the experience of homelessness, disproportionately fall on BIPOC households.[5]

This racial disparity reflects the impacts of historical and ongoing racial injustice and discrimination in housing, employment, and educational opportunities that have systematically disadvantaged people of color. A primary driver of our nation’s racial wealth gap is decades of racial discrimination of real estate agents, banks and insurers, and the federal government prevented people of color from purchasing homes. This took the form of federal housing policy denying borrowers access to credit in Black communities, physical violence, and covenants banning home sales to Black people trying to live in predominately white neighborhoods.[6] Even as our nation ended many of these overtly racist practices, including through the passage of the 1968 Fair Housing Act, insidious forms of discrimination persist and lock communities of color out of building wealth through homeownership, educational attainment, and opportunities to make equitable wages.

Program Summary

The Housing Choice Voucher program was established in 1974 in Section 8 of the repeatedly amended United States Housing Act of 1937. The Section 8 low-income housing program is two programs: the Housing Choice Voucher program, which are portable subsidies that families can use to rent housing of their choice in the private market, and the project-based Section 8 program, which is rental assistance that is attached to a unit of privately owned housing. The Section 8 program began primarily as a project-based rental assistance program.[7] By the mid-1980s, project-based rental assistance came under criticism for being too expensive and not equitably serving Black households living on low incomes by segregating them in high-poverty areas. Due to these concerns, Congress shifted to providing direct rental subsidies so that people could decide for themselves where they want to live.

Today, the Housing Choice Voucher program under Section 8 is the largest federal low-income housing assistance program, providing over 2.3 million households tenant-based rental assistance.[8] The program has three primary goals:

The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and a network of about 2,170 state and local public housing agencies (PHAs) administer the HCV program.[10] PHAs distribute vouchers to qualified households who then conduct their own housing search. An individual must find an available rental that meets quality program requirements and whose landlord accepts vouchers as payment. The household pays 30 percent of its adjusted gross income towards housing costs. The value of the voucher covers the remaining rent balance up to a limit (called a payment standard) set by the local PHA that is based on HUD’s Fair Market Rent estimates.[11] When a household receives a voucher, it usually has 60-120 days to find an apartment, though extensions are sometimes possible, or it loses the voucher.

Unlike public housing agencies, tribal nations are not eligible to apply for housing choice vouchers since the passage of the Native American Housing Assistance and Self-Determination Act (NAHASDA) of 1996. NAHASDA provides block grant funds directly to tribal nations to provide affordable housing-related opportunities for eligible households living on reservations and in other tribal areas but restricts tribal nations from accessing many other HUD programs.

Funding

The Housing Choice Voucher program receives discretionary funding in annual appropriation bills in an amount determined by Congress. Unlike other federal anti-poverty programs, like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, the HCV program is not an entitlement program, meaning that not everyone who qualifies and applies for assistance receives it.

Most PHAs receive voucher renewal funding each year, adjusted for inflation. That amount is capped at the total number of vouchers an agency has been awarded since the start of the program and the cost of the authorized vouchers in use during the prior year— not based on need.[12] Congress also funds incremental vouchers, which are new vouchers that specifically address the housing needs of a particular group, as opposed to vouchers that add to a community’s overall voucher pool.[13] Examples include the Veteran Affairs Supportive Housing program for homeless veterans and the Family Unification Program for families for whom inadequate housing has caused or threatens to cause a child to be removed from their family or prevents family reunification.[14]

Eligibility

Housing Choice Vouchers serve households living in deep poverty. HUD sets income limits to determine eligibility for housing vouchers based on estimates of median income and fair market rents in an area. By law, 75 percent of all new vouchers each year must go to households living on extremely low incomes, defined incomes no more than 30 percent of the Area Median Income or the federal poverty line, whichever is higher.[15] In addition, state and local PHAs have the flexibility to set admission preferences for households that meet specific criteria such as veterans, working families, families fleeing domestic violence, or on an applicant’s housing needs such as those experiencing homelessness.

Attributes of Voucher Assisted Montana Households

In Montana, a two-person household can make no more than $17,300 to be considered extremely low income.[16] To put into context, someone making minimum wage in Montana at 40 hours a week earns only $18,200.[17] Even so, the average yearly income of a voucher-supported Montana household falls below this standard at $12,360.[18]

Among households that would most benefit from rental assistance would be the one in four Montanans living on extremely low incomes or incomes at or below the poverty level. Understandably, these households must pay very high shares of their income on rent— 68 percent pay more than half of their limited incomes to afford their homes.[19] Severely cost burdened households in this situation are more likely than others who pay affordable levels of rent, including those living on poverty level incomes, to sacrifice meeting other essential needs like healthy food and medicine in order to pay the monthly rent.

Today, 5,728 Montana households, which include tenants living with disabilities, families raising children, and senior citizens who live in these households, use a voucher. When disaggregated by race, voucher assisted households reflect the state’s demographics, with white and American Indian or Alaska Native (AI/AN) individuals and families making up the largest share. The most recent data shows that 79 percent households receiving HCVs are white, and 14 are AI/AN.[20]

Value of Housing Vouchers

Housing vouchers can be a powerful tool to address persistent poverty and longstanding racial inequity by directly redressing affordability problems. When properly implemented, vouchers can stabilize families and give them greater choices about where they live, access to higher-opportunity neighborhoods, and meet their legal obligation to reduce the housing segregation of Black households and concentrated residential poverty. Multiple studies have found that the voucher program can deliver important, tangible outcomes.

Barriers to Program Success

There is evidence that the HCV program has fallen short of achieving its intended goals. The way the program is designed and administered contributes to the housing choice and mobility challenges that vouchers are meant to redress. Inadequate funding, an area’s rental market and availability of affordable housing stock, and quality of landlord relations all factor into current usage barriers.

Voucher Availability

Housing vouchers are not an entitlement benefit and Congress does not appropriate the level of funds needed for housing assistance. The number of households that qualify for housing vouchers far exceed the number of vouchers available. Due to a shortage of resources, most public housing agencies maintain long wait lists or use a lottery to determine which households can join the waitlist. Many PHAs have closed their waitlists because applications far exceed the number of vouchers they can administer. Households placed on a waiting list typically wait years before receiving a voucher. In Montana, the average wait times for people on a waitlist for an HCV is 25 months.[25] There are more than 5,000 people on a waitlist in Montana, as of January 2020.[26] Many other families cannot get on a waitlist. According to one 2016 survey, over half of agencies were not allowing any additional applicants on their waitlists. Thus, the number of people on voucher waitlists and the length of time to receive a voucher are incomplete measures of the unmet need for assistance because many eligible households do not make it onto a waitlist in the first place.

Source of Income Discrimination

The “choice” component of the Housing Choice Voucher program is not fully realized. Even when a household receives a housing voucher, they still must find landlords that are willing to accept a voucher as rent payment before the voucher expires and goes to someone else. Federal law does not prohibit landlords from discriminating against renters based on their source of payment. In the absence of federal protections against voucher holders, landlords routinely discriminate against renters with housing vouchers, particularly landlords in higher-rent areas with high-quality schools, jobs, and transportation.[27] Explicit or implicit bias continue to undermine housing options for BIPOC households. Only 12 states and 87 local governments have passed source-of-income laws prohibiting landlords from discriminating against voucher holders; Montana is not among them.[28]

Rent remains unaffordable

Another problem is that voucher amounts can be too low to move a family out of high-poverty, racially segregated neighborhoods. Housing Choice Voucher rental subsidies are capped by a payment standard based on the Fair Market Rent of an area. Payment standards based on area Fair Market Rents are often too low to cover rent in neighborhoods with low poverty, low crime, and strong schools, which perpetuates the racial and social segregation vouchers are intended to mitigate.[29] In Montana, for example, Missoula County’s payment standards mean that someone looking for a one-bedroom rental needs to find one for $849 or less, a two-bedroom rental needs to be $1,076 or less.[30] The rental market in the city of Missoula is one of the most expensive in the state, as well as having very low vacancy rates, and it is challenging for someone living on a very low income to find a place where they do not pay more than 30 percent of their income on rent.

Federal Policy Interventions

All Montanans deserve a safe, affordable, and stable place to call home. The federal Housing Choice Voucher program is an important tool that we can use to achieve that ideal. There are several actions Congress, HUD, and public housing authorities should take to improve implementation of the HCV program. Making these comprehensive reforms will be a critical step towards achieving true housing choice and mobility.

MBPC is a nonprofit organization focused on providing credible and timely research and analysis on budget, tax, and economic issues that impact low- and moderate-income Montana families.