All Montanans should have full and easy access to exercise their right to vote. Indigenous people disproportionately face barriers to voting access. Denying Indigenous Montanan’s full participation in the democratic process and limiting their ability to influence policy affects their communities and families. Throughout history, federal voting policy brought contradictory and often volatile actions toward Indigenous people. Montana is no exception to the same long history of voter suppression tactics. Despite landmark legislation and major court decisions intending to protect voter rights, Indigenous people continue to face barriers that impact voter participation.

From unfair redistricting plans to discriminatory voter registration procedures, these policies continue to deny Indigenous people their constitutional right to vote. Long after the re-affirmed protections from the 1965 Voting Rights Act, Montana continues to place legal barriers preventing Indigenous people from voting.[1] To ensure every citizen has an equal opportunity to take part in all elections and uphold the voting rights of American Indians, Montana should:

U.S. Barriers to Indigenous Voting

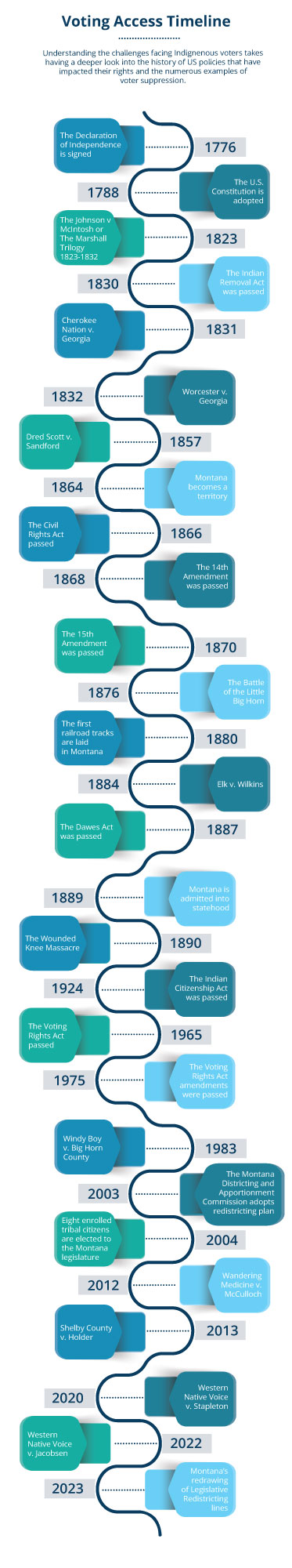

Voting power for Indigenous people is critical to improving their socioeconomic status, self-determination, land rights, water rights, housing, education, and health care.[2] Restrictions and barriers to this type of political power make it harder to secure access to representation and the federal and state resources that flow from it. Knowing why voting matters involves understanding and recognizing previous historical barriers and legislative actions impacting the Indigenous vote. The long history of voting rights policies in the United States and Montana gives insight into why we continue to see legislation that hinders the right to vote for Indigenous people.

Late 1700's

History reveals obstacles at every turn regarding voting rights for Indigenous people. At the time of the Declaration of Independence in 1776, only people who owned land could vote – most of whom were white landowning males. Some states even administered religious tests to ensure only Christian men voted.[3] Interactions with American Indians in 1778 began taking the form of treaty negotiations – the first treaty was signed with the Delaware Indians.[4] Treaty-making continued until about 1871, but tribal nations remained sovereign and considered independent from U.S citizenship. The U.S. Constitution was adopted on June 21, 1788, granting states the power to establish standards for voting rights but voting remained mostly only for white landowning males.[5]

Early 1800’s

From 1823 to 1832, more legal definitions of tribal nations’ relationship to the United States started to form. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall authored the Marshall Trilogy – Johnson v. McIntosh, Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, and Worcester v. Georgia.[4] These laid the foundation for federal Indian law and the roots of the federal-tribal trust relationship. It also established the treatment of tribal property and resources. These cases determined that:

Under intense pressure from eastern politicians and President Andrew Jackson, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act of 1830 calling for the removal of all eastern tribal nations to lands west of the Mississippi.[6] This massive removal forced over 80,000 American Indians to surrender their homelands and move west. The Act required the government to negotiate treaties of removal with all the eastern tribal nations. Few American Indian people were interested in moving away from their homelands. In early attempts, the government offered individual Indian families the opportunity to stay on their land, gain citizenship, and avoid removal. However, citizenship did not necessarily include the right to vote.[7] That privilege was generally left up to the impulse of local officials.

Dred Scott v. Sandford

The mid-to-late 1800s continued to see policies toward Indian removal, assimilation, and the denial of voting. One of the most overtly race-based U.S. Supreme Court decisions of 1857, Dred Scott v. Sandford, explicitly denied those of African descent the rights and privileges that the Constitution bestows upon American citizens, but the decision also allowed for a tribal citizen to deny their tribal identity to become a U.S. citizen. However, as was the case before, citizenship did not necessarily include the right to vote.

“They [the Indian tribes] may without doubt, like the subjects of any foreign government, be naturalized by the authority of Congress and become citizens of a state and of the United States, and if an individual should leave his nation or tribe, and take up his abode among the white population, he would be entitled to all the rights and privileges which would belong to an emigrant from any other foreign people.”[8]

Civil Rights Act of 1866

After the American Civil War, in 1866, when the Senate started debating the Civil Rights Act, concerns arose about the bill’s broad language conferring citizenship to all American Indians. The Civil Rights Act declared all persons born in the United States to be citizens "without distinction of race or color, or previous condition of slavery or involuntary servitude.” Although President Andrew Johnson vetoed the legislation, the 39th United States Congress overturned that veto, and it became law.[9] The final bill granted citizenship to American Indians “who are domesticated and pay taxes and live in civilized society” and was “incorporated into the United States.”[10]

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments

In 1868, Congress ratified the Fourteenth amendment giving this a broad definition of citizenship:

"All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” (U.S. Constitution, amend. 14, sec. 1)

While this amendment nullified the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott v. Sandford decision denying those of African descent the rights and privileges of the Constitution, citizenship for American Indians still depended on the authority of Congress and the states.

By 1870, the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment ensured that the right to vote could not be denied based on race. This drastically expanded the right to vote, at least in the Constitution’s text.[11] However, in the decades that followed, many states, particularly in the South, used a range of barriers, such as poll taxes and literacy tests, to deliberately reduce voting by people of color.[3] Though the Fifteenth Amendment granted all U.S. citizens the right to vote regardless of race, American Indians (not taxed or naturalized) still could not enjoy the rights granted by this amendment.[12]

Elk v. Wilkins

In 1884, the Supreme Court issued one of its most contentious decisions, stating that American Indians were not citizens by birth under the Fourteenth Amendment and could be denied the right to vote. The case of Elk v. Wilkins dealt with a birthright citizenship claim and ruled against Elk. John Elk was an English-speaking American Indian who gave up his tribal affiliation, moved off-reservation, paid taxes, and then tried to vote.[10] Wilkins was an election officer who denied Elk from submitting a ballot because Elk was an “Indian” and therefore not a citizen. Even though Elk had severed his tribal relation and “adopted the ways of the white man,” the court claimed it did not make him a citizen. Elk had never been “naturalized” or “had not become a citizen through any statute or treaty.” Not all Supreme Court Justices agreed on this. Justice John Harlan wrote a dissenting opinion.[7] Harlan maintained that Elk was an “Indian taxed” and entitled to all the same privileges under the Constitution and the Fourteenth Amendment as other citizens, including the right to vote. Harlan also pointed out that Elk was counted in every apportionment of representation in the Legislature. No one attempted to exclude him from Nebraska citizenship for those purposes.

The Dawes Act of 1887

When the devastating impacts of the Dawes Act of 1887 struck, it forced assimilation and divided tribal nations’ communal landholdings into allotments leading to multiple owners, including millions of acres passing out of trust into non-Indian homesteading.[4] The act also legally granted citizenship to American Indian men who completely disassociated themselves from their tribal nation, making those men technically eligible to vote. Among other things in this era, the U.S. government forced Indigenous children off to boarding schools to receive instruction not only in reading and writing but also in social and domestic customs of white America.[1][2]

It is important to remember that violent encounters between the U.S government and tribal nations continued well into the late 1800s. To provide context, the defeating of General George Armstrong Custer in 1876, occurred at the Battle of the Little Big Horn. In 1890, only a year after Montana became a state, the U.S. Army arrived on Lakota reservations leading to the Wounded Knee Massacre. These violent encounters, fueled by the expansion of the railroad, improved weaponry resulting from the Civil War, and a larger and better-trained army, rendered Congress unwilling to negotiate further with the tribal nations as independent nations.[7] American Indians no longer found themselves able to protect their rights through treaties with the United States and, not being citizens, unable to rectify grievances through the courts or ballot box.

Undermining the Indigenous Vote in Montana

Limitations on voting access for Indigenous people have existed since Montana became a state in 1889. The original Montana Constitution restricted service in the state militia and the holding of office to U.S. citizens only, which restricted American Indians who were not classified as citizens.[1] By 1897, the Montana attorney general determined that American Indians were only eligible to vote if they owned property and lived outside reservation boundaries.[1] In 1919, a further codification of the law prohibited the creation of electoral districts on American Indian lands or the location of precincts at trading posts that might be accessible to American Indians.[1]

Following the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, American Indian candidates ran for office in Montana without success in the 1924, 1928, 1932, and 1934 elections.[1] Two pieces of state legislation in 1937 further disenfranchised American Indians. The first canceled all voter registration as of June 1, 1937, and the second required that registered voters be tax-paying residents of their precincts. This second law remained on the books until 1975, ten years after the 1965 enactment of the Voting Rights Act.[1]

Racial discrimination by vote dilution or vote denial strategically reduced large populations of people of color from voting. These tactics remained largely in effect even after the Indian Citizenship Act up until Congress passed the Voting Rights Act (VRA) of 1965.[11] The VRA gained greater relevance to Indian Country after the 1975 amendments added Section 203 protections for language minorities.[2] The following decades brought many legal challenges to racial discrimination in states’ voting practices.

Windy Boy v. Big Horn County

Relying upon the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments and the various sections of the VRA, lawsuits against discriminatory voting practices were filed in Montana. One of the most notable lawsuits was Windy Boy vs. Big Horn County, also known as the “Second Battle of the Big Horn.”[1] No American Indian had been elected to the County Commission in Big Horn, Montana, under the at-large electoral system, despite American Indians making up 41 percent of the county’s voting-age population at the time. The Windy Boy vs. Big Horn lawsuit of 1986, led to the U.S. District Court adopting single-member districts for the Board of County Commissioners and the school board in Big Horn County. The next election resulted in the successful candidacy of the first American Indian County Commissioner in Big Horn County.

The year 2003 brought an appointment of a new Montana Districting and Apportionment Commission which included Janine Windy Boy, a citizen of the Crow Nation and lead plaintiff in the Windy Boy litigation. This commission submitted a redistricting plan to have American Indian majorities in six of Montana’s 100 House Districts and one of the 50 Senate Districts.[1] The Legislature countered by enacting House Bill 309 to invalidate the redistricting plan and amend the Montana Constitution. Governor Judy Martz signed HB 309 into law on February 4, 2003. However, by July 2003, the Montana First Judicial District Court held that HB 309 was unconstitutional and ruled that the Secretary of State must accept the redistricting plan as originally submitted. Following the updated redistricting plan, voters elected eight tribal citizens to the Montana Legislature.

Modern Litigation

Even though Congress designed the Voting Rights Act to ensure state and local governments could not pass laws or policies denying citizens the right to vote based on race, laws continue to disproportionately affect the Indigenous vote.

2012 Wandering Medicine vs. McCulloch Tribal Nations wanted equal access to in-person voting through permanent satellite voting offices. Ultimately, the state and county election officials settled the case out of court with the tribal plaintiffs, agreeing to establish satellite offices on the reservations twice a week through Election Day.[13] Ideally, these offices should offer more days in the week and hours in the day.

2013 Shelby County vs. Holder At issue was whether a provision in Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act was unconstitutional by requiring jurisdictions with a history of discrimination to submit proposed changes in voting procedures to the U.S. Department of Justice.[11] The decision, upholding what was current law, paved the way for states and jurisdictions with a history of voter suppression to enact restrictive voter identification laws. Following the ruling, 23 states created new obstacles to voting in the decade leading up to the 2018 elections.[3]

2020 Western Native Voice vs. Stapleton The courts permanently struck down the Montana Ballot Interference Prevention Act (BIPA) passed by the 2019 Legislature, which set an arbitrary limit on the number of ballots an individual could collect and restricted the categories of individuals who were permitted to collect ballots.[14] These limitations can suppress turnout on rural reservations, where geographic and socioeconomic barriers to voting make ballot collection even more critical.

2022 Western Native Voice vs. Jacobsen On January 12, 2022, Western Native Voice, Montana Native Vote, and several tribal nations filed an injunction to prevent discriminatory voting laws passed by the Montana Legislature, including House Bill 176, which ends same-day registration, and House Bill 530 which attempts to block organized ballot collection on rural reservations.[15] The case remains active at the time of this report.

Indigenous Voter Turnout

Despite ongoing efforts that undermine Indigenous people’s ability to cast their ballot, Indigenous populations in Montana celebrated a record-breaking turnout in reservation areas with a 5 percent increase from the 2016 election to the 2020 election.[16] Roughly 89 percent of voters received an absentee ballot for the 2020 election. Because 45 of 56 counties moved to an all-mail election due to the COVID-19 pandemic, this number is higher than in years past. Of voters who received an absentee ballot, 90.2 percent of ballots were returned.[16] Nationwide, we see that work for increasing voter registration in Indian Country is needed. Only 66 percent of American Indians are registered, and over 1 million eligible voters are not registered.[2]

Factors discouraging political participation

Despite the protections offered by the Voting Rights Act and other legal protections, field hearings in 2017 and 2018 conducted by the Native American Voting Rights Coalition revealed many barriers still exist.[2]

Barriers exist across the social, economic, digital, and geographic landscapes of Indian Country. Due to race-based policies and systemic barriers, the poverty rate for Indigenous people reported in 2017 was estimated to be 26.8%, compared to 14.6% for the nation as a whole.[17] Economic barriers coupled with long distances and poor road conditions to election services make engaging with the election system difficult as it requires resources to drive a vehicle, pay for car insurance, gas, etc.[18] When then adding limited hours and locations to election offices and post offices, it makes voting far more challenging. Compounding barriers also include a lack of access to cellular service, computers, and broadband resources, which is profoundly felt in Indian Country.[2]

Additionally, Indigenous candidates face difficulty getting on a ballot to represent themselves because of discrimination and the lack of resources in their campaigns.[2] Along with these barriers, there is also the ever-so-relevant issue of redistricting and the potential for gerrymandering.

Redistricting and Gerrymandering

Redistricting is the constitutionally required redrawing of the geographic lines that divide districts for the U.S. House of Representatives, state legislatures, county boards of commissioners, city councils, school boards, and other local bodies.[19] It takes place every ten years after the United States conducts a census to determine how many people live in the United States and its territories. Redistricting matters because it controls access to political representation. It influences who runs for office and who is elected. Elected representatives make many decisions that impact the daily lives of citizens. Elected officials make decisions about acknowledging tribal sovereignty, honoring treaties, and protecting the land. The maps created in 2023 will be in use for ten years. The abuse of redistricting is called gerrymandering – when boundary lines are drawn with the intention of influencing who gets elected.[20] In 2022, the Montana Districting and Apportionment Commission will draw legislative districts and submit their plan for review to the 2023 Legislature. The commission can then choose to follow or pass on recommendations submitted by the Legislature. Public commenting periods will occur during the 2022 calendar year.

Conclusion

All Montanans should have equitable access to participate fully within our democracy. A long history of voting rights policies gives insight into where current oppressive policies stem. There must be ongoing education and partnering between tribal nations and policymakers to address these barriers.

To ensure every citizen has an equal opportunity to take part in all elections and uphold the voting rights of American Indians, Montana should:

Special Acknowledgement and More Information

Knowing your rights, participating in the legislative session, and engaging in the political activities are fundamental to increasing voter participation and protecting the right to vote. MBPC partners with community-based organizations like Western Native Voice, Indigenous Vote, and Montana Women Vote to help activate communities. Citizens can learn how to register to vote at Western Native Voice’s page here https://westernnativevoice.org/voter-registration/.

MPBC would like to give special thanks to Western Native Voice for their collaboration on this report.

For a more in-depth report on voting access in Indian Country, check out Obstacles at Every Turn – Barriers to Political Participation Faced by Native American Voters.

MBPC is a nonprofit organization focused on providing credible and timely research and analysis on budget, tax, and economic issues that impact low- and moderate-income Montana families.