Montana is the only state constitutionally requiring American Indian cultural heritage and history to be taught in classrooms. This provision is known as Indian Education for All (IEFA). The constitution states that every Montanan, whether native or non-native, be encouraged to learn about the distinct and unique heritage of American Indians in a culturally responsive manner. While the legislature has taken steps over the years to support the continuation of IEFA, tribal nations are advocating for improvements in regulation and funding requirements. For years, the program had little funding to make the constitutional mandate a reality in classrooms. But in 2005, a lawsuit was able to change that and secure funding to both local districts and the Office of Public Instruction (OPI). Since then, IEFA has received about $3.5M annually over the last decade. However, new issues have been brought to the surface, including a lack of reporting requirements that have caused many tribal nations and concerned parents to question whether the funding is being spent in the correct places. Tribal nations in Montana are rallying again to ensure educational environments never become a place of harm and instead counter past colonial violence with education.

IEFA: 1970s to 2023

In 1972, American Indian people from across the state traveled to Helena to testify at the Montana Constitutional Convention. Before this point, there were no regulations for teaching the history and culture of American Indians in classrooms. This made it difficult to know if children were being taught consistent and accurate information. Many American Indian students came to testify to advocate for the right to see their culture and identity represented in schools. Legislators listened and came to echo their sentiments, and Montana became the first and only state to have this provision in their constitution. The creation of Article X came at the end of the boarding school era, which upheld colonial policies in classrooms geared towards cultural erasure and forced assimilation. American Indian children were often forcibly removed from their families and made to attend schools where they were met with conditions that caused lasting physical and emotional trauma, and many did not return home.

However, it would be 25 years before IEFA would become a constitutional mandate for state agencies to uphold. Throughout the years, funding for the program has been a major issue, and in 2005 a lawsuit confirmed that the lack of funding was unconstitutional. Since then, IEFA has maintained a $3.5 million budget annually, but the implementation of IEFA still needs to be consistent. According to state records, nearly half of the funding goes unaccounted for per year. Without proper reporting systems, it is difficult to know if funding is correctly spent on Indian Education materials or elsewhere.

The lack of reporting requirements for IEFA funding is a significant concern for many tribal nations in protecting the well-being of American Indian children. A class action lawsuit was filed in July 2021, Yellow Kidney et al. v. Montana Office of Public Instruction. This landmark case represents all tribal nations located in Montana and concerned parents and students affected by the improper management and implementation of IEFA. It is a giant step forward and has already caused important legislative changes, including HB 338, which enforces reporting IEFA funds by school district and increases communication between tribal nations and public schools.

Indian Education for All in the Classrooms

With so many conversations around standards of implementation and funding, it is essential to review what Indian Education looks like in classrooms. According to the OPI IEFA staff, implementation of IEFA is broader than adding a unit on Indian history or tradition. Instead, it is the intention that IEFA addresses broader issues of multicultural education, that it occurs through authentic integration throughout all curricula, and that it is based in best educational practices. OPI has come out with over 400 crucial resources for educators that are responsive to the unique factors for schools and educators, such as school size and classroom demographics.

Teachers are provided with lists of resources, such as books and lesson plans, that have been reviewed and could be implemented in their classrooms. For example, one option for implementing IEFA while teaching Language Arts to Kindergarteners is a children’s book that retells an American Indian child’s experience attending a powwow. The lesson plan touches on several key principles called “essential understandings,” such as the importance of tribal diversity and the different beliefs and oral histories that tribal nations have across the United States.

As children grow and develop other critical thinking skills, so too do the resources and level of understanding they are taught. Another example is taking the same subject, Language Arts, but looking at the resources available to 11th and 12th graders. One of the books available for their curriculum is about The Battle of the Little Bighorn, in which they build on all the foundational points they have gone over in past years but add historical events that open classroom discussion to different topics like tribal sovereignty and Federal Indian Policy.

Studies show that multicultural learning environments benefit all students. Despite this, funding for the program have shown few increases in the last decade. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the allocation to OPI for the IEFA program had only seen a 7 percent inflationary increase in the last decade. But during the same time frame, total spending on education has increased by 23 percent and enrollment in public schools increased by 15 percent.

Why Indian Education for All is Necessary

IEFA protects American Indian children and works to counter and remedy past harmful environments created by colonial policies in classrooms. In Montana public schools, about 14 percent or 20,535 of children are American Indian/Alaskan Native, with that number steadily increasing each year. Many American Indian children face barriers in and outside of the classroom that affect their likelihood to graduate, standardized test scores, and grades, known as the achievement gap. An example of one of these indicators is graduation rates. In 2021, the graduation rate for American Indian students was about 68%, and 18% lower than the state average.

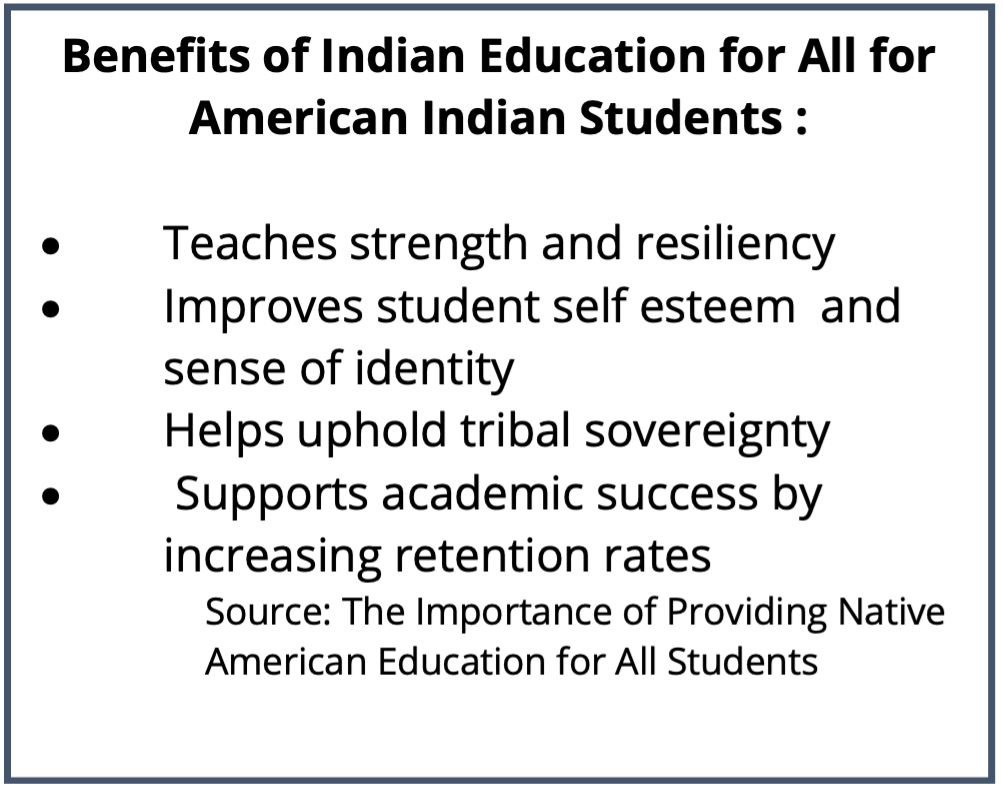

However, research shows that cultural representation in the classroom positively affects children whose culture is accurately incorporated into the curriculum; including an increased feeling of belonging, more confidence in their abilities, and accelerated academic achievements.

Policy Recommendations for the Legislature:

MBPC is a nonprofit organization focused on providing credible and timely research and analysis on budget, tax, and economic issues that impact low- and moderate-income Montana families.