Every 10 years, states engage in redistricting - a process to redraw the geographic lines that divide districts for the U.S. House of Representatives, state legislatures, county commissioners, city councils, school boards, and other local bodies. Redistricting follows the census, which attempts to count each resident in the country and is used to adjust the boundaries to accommodate for population increases or decreases within districts. According to the 2020 census, “American Indians alone or in combination” make up 9.3% of Montana’s population.[1] Montana districts must be drawn fairly to reflect the communities. Fair representation is a fundamental principle of democracy. Deciding where to draw these lines significantly affects the political actions taken for the next ten years.

This upcoming fall, Montana’s five-member, independent Districting and Apportionment Commission will decide on a map for legislative districts, which they will then submit to the 2023 Legislature for review before the Commission makes the ultimate decision on the map’s adoption. As part of the process, the Commission will take critical public comments on the impact that these districts have on communities in Montana. Times and locations for hearings are available online, along with agendas for each meeting.

Voting Rights

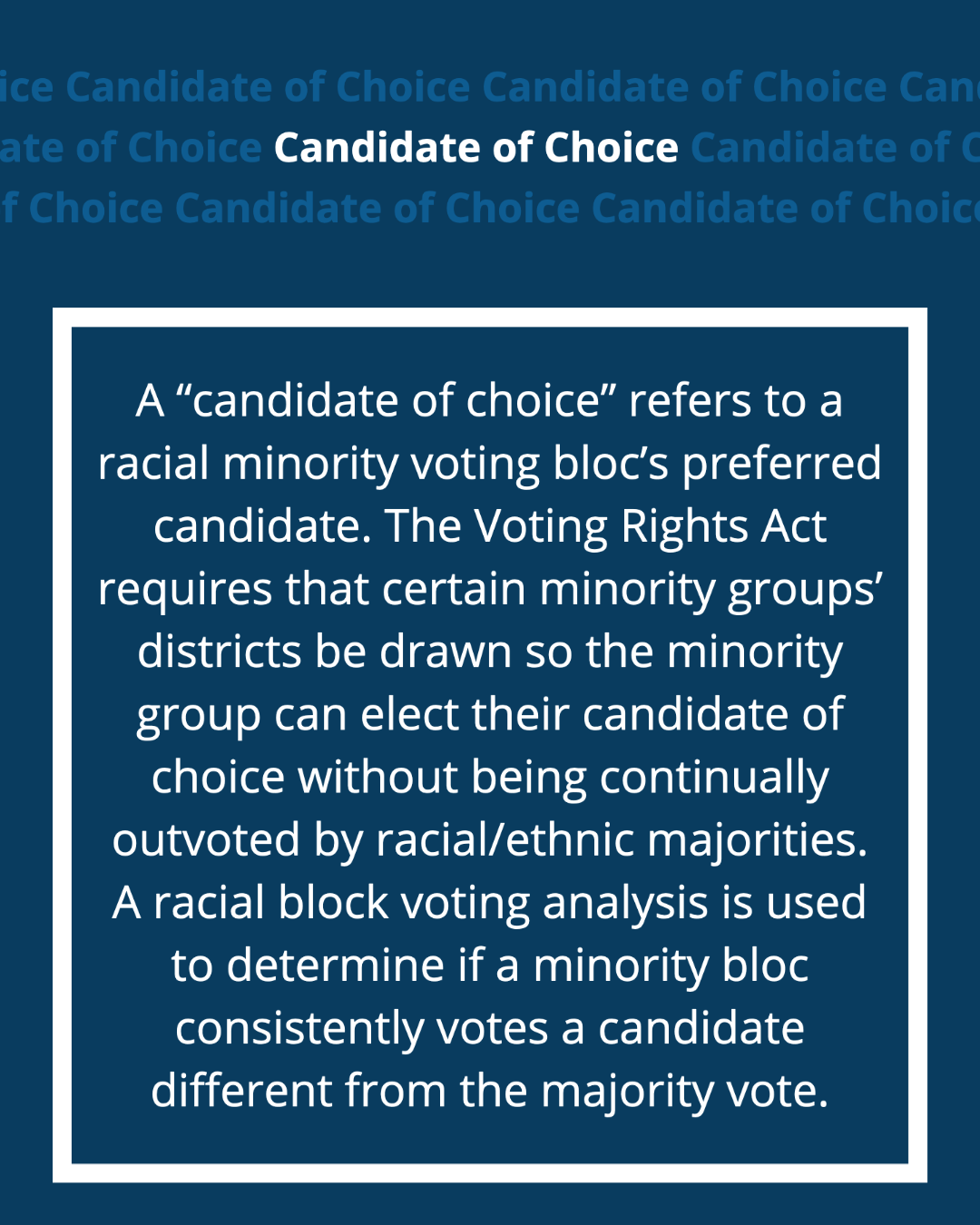

Article I, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution mandates redistricting to determine how to apportion the House of Representatives among the states. As states redraw their state legislative districts, states must comply with the federal Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) to protect the voting rights of minority voters. The Voting Rights Act (VRA) of 1965 prohibits voting processes that result in the restriction of voting rights based on a voter’s race, color, or language minority status.[2] One common tactic that violates the VRA is minority voter dilution. Vote dilution refers to separating minorities into several districts, creating an ineffective minority voting group, or arranging minorities into a small number of districts, creating a disproportionate majority.

In a most recent voter dilution case in Alabama, Merrill v. Milligan, a unanimous three-judge court blocked Alabama’s newly drawn congressional map based on its violation of the Voting Rights Act.[3] The Court ordered the Alabama State Legislature to draft a new map to include two districts where Black voters could elect candidates of their choice. (The case currently is pending appeal.) Other recent similar litigations include Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians et al.[4] v. Alvin Jaeger et al. and Walen et al. v. Burgum et al.[5]

Historical Impacts

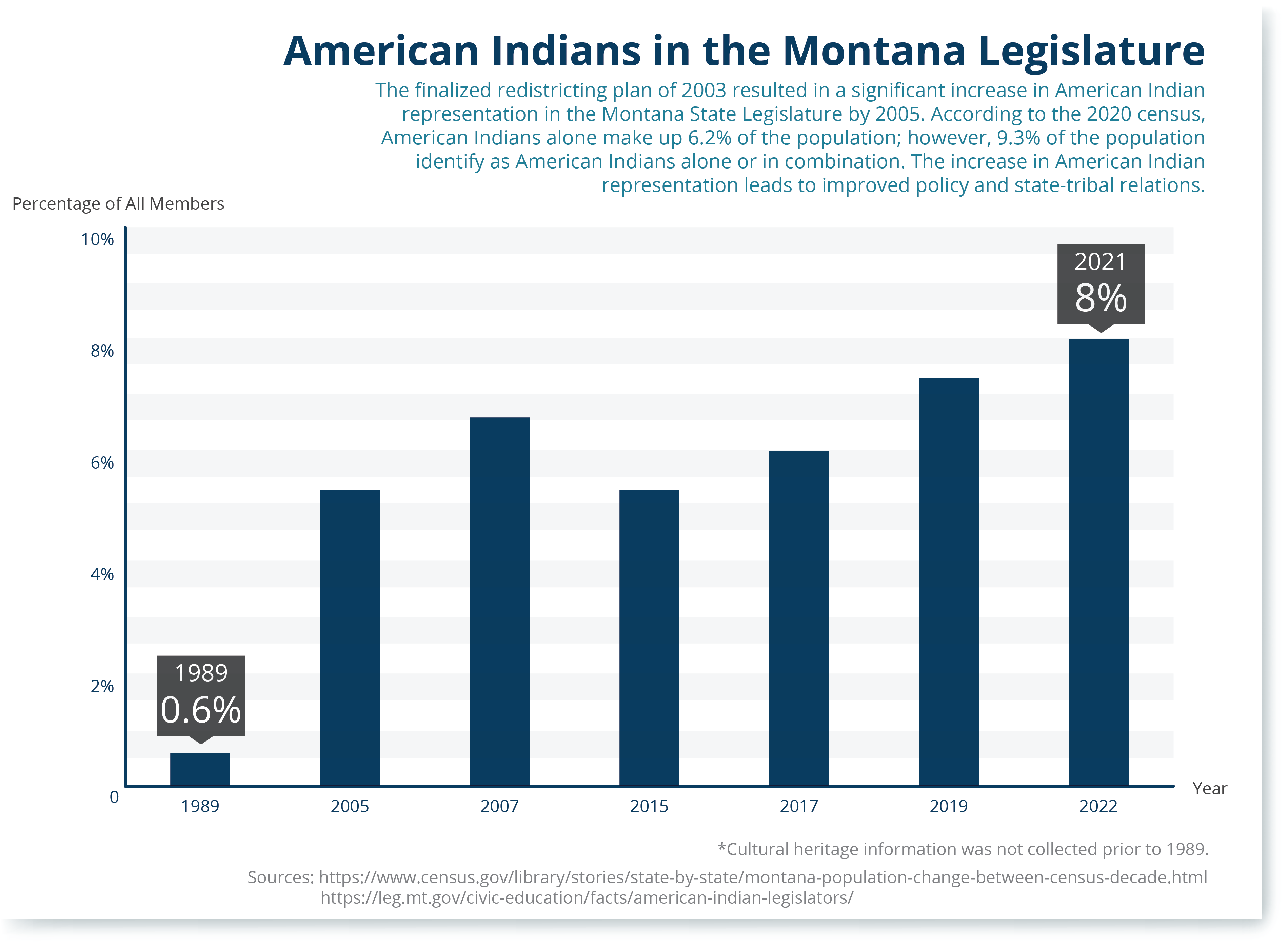

Despite a history of attempts to block fair districting in the courts and the Legislature, Montana’s independent redistricting Commission has led the nation in establishing equitable and fair districts to ensure native representation in the Legislature. In 2003, based on 2000 census data, the districting Commission established six Indian-majority house districts and three Indian-majority senate districts.[6] The map created districts of over 50 percent American Indian voting age population where the population was geographically compact and sufficient in number. While the Montana legislature attempted to block the independent Commission’s map, the court ultimately upheld the map and ruled that the Secretary of State must accept the redistricting plan as originally submitted. Following the updated redistricting plan, voters elected eight tribal citizens to serve in the Montana Legislature in 2005.[7] Today, Montana is viewed as a leader in electing an American Indian legislative caucus proportionate to the state population, but that could all be put at risk with newly drawn maps.

Why It Matters

Redistricting matters for Indian Country because it controls access to political representation. It influences who runs for office and who is elected. Elected representatives make many decisions that affect our daily lives and must be checked. Because redistricting can dictate political power, it must be subject to political scrutiny as it risks becoming a weapon to neutralize minority voting power. Equal access to resources and representation for everyone results from fair districting.

State-Tribal Relations Timeline

As noted previously, legislatures play an influential role in defining a state’s relationship with tribal nations. Through the efforts of American Indians and receptive non-Indian legislators and citizens, the Montana Legislature recognizes that tribal citizens are also Montana citizens who contribute to the state's well-being. What follows is a timeline of meaningful advancements resulting from fairer redistricting practices and improved state-tribal relationships.

1951 - Montana Legislature creates the Coordinator of Indian Affairs position to recognize the need for American Indians to communicate with the state government.[8]

1972 – Montana Constitution is revised in its entirety and includes the addition of Article 10, Section 1(2), which states that “the state recognizes the distinct and unique cultural heritage of the American Indians and is committed in its educational goals to the preservation of their cultural integrity.”[9]

1981 - Montana Legislature enacts the State-Tribal Cooperative Agreements Act, authorizing public agencies to enter cooperative agreements with tribal governments.[10] As of 2017, public agencies and tribal nations entered more than 550 agreements.[11]

1989 - Montana Legislature establishes the Committee on Indian Affairs, now called the State-Tribal Relations Committee, as a permanent, interim committee. The Committee acts as a liaison with tribal governments, encourages state-tribal and local-tribal cooperation, proposes legislation, conducts interim studies, reports its findings, and makes recommendations to the Legislature.6

1993 – Montana Legislature amends the State-Tribal Cooperative Agreements Act to allow for state-tribal revenue-sharing agreements specifically.[12] In 2016, state-tribal revenue-sharing agreements enabled tribal nations to collect almost $11 million in shared tax revenue from the on-reservation sale of tobacco, alcohol, and gasoline.[13]

1995 – Montana Legislative Council’s Committee on Indian Affairs, the predecessor to the State-Tribal Relations Committee, publishes Tribal Nations in Montana: A Handbook for Legislators to educate legislators about tribal culture, sovereignty, and government policies related to American Indians in Montana. The handbook was among the first resources of its kind in the United States.6

1995 – Montana Legislature passes House Bill 544, sponsored by Representative Carley Tuss and codified as MCA 20-25-428, to appropriate $1.4 million to reimburse tribal colleges for providing educational services provided to resident non-Indian students. This funding is now known as the Tribal College Assistance Program.[14]

1997 – Montana Legislature passes Senate Bill 84, sponsored by Senator Greg Jergeson, to make the funding formula for the Tribal College Assistance Program permanent. However, the funding distribution remains contingent upon a line-item appropriation.[15]

1999 - Montana Legislature passes House Bill 528, sponsored by Representative Carol Juneau and codified as MCA 20-1-501, to implement Article 10, Section 1(2), of the state Constitution, creating what is today known as Indian Education for All.[16]

1999 – Montana Legislature passes the Native American Economic Development Act, creating the State Tribal Economic Development (STED) Commission. The STED Commission comprises 11 representatives, including one from each of the eight tribal governments in Montana. Itis responsible for assisting, promoting, developing, and proposing recommendations for accelerating on-reservation economic development.[17]

2003 – Montana Legislature passes House Bill 608, sponsored by Representative Jonathan Windy Boy and codified as MCA 2-15-142, 143. HB 608 creates mechanisms for holding the state accountable to tribal nations. The bill does this by providing for tribal consultation in the development of state agency policies that directly impact tribal nations, authorizing annual training for state employees, providing for annual meetings between state and tribal government officials, and requiring the state to produce an annual report on its work and investments in Indian Country. HB 608 also defined the principles to guide the state-tribal relationship. The National Conference of State Legislatures and the National Congress of American Indians developed these principles.[18]

2005 – Through his first executive order, Governor Brian Schweitzer creates the Governor’s American Indian Nations (GAIN) Council to ensure that all activities between tribal nations and the state are conducted in a government-to-government manner, and that state agency activity with tribal nations includes tribal consultation.[19]

2005 - Governor Brian Schweitzer’s administration creates the GAIN database to track the extent of the state’s involvement with tribal governments.18

2005 – Governor Brian Schweitzer convenes the first-ever state-sponsored meeting of tribal leaders, regional directors of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and Indian Health Service, and key members of his staff and state agencies to begin creating innovative solutions to some of the issues identified as priorities by tribal nations in Montana.18

2005 – Montana Legislature approves Governor Brian Schweitzer’s executive budget request for $3.2 million for fulfilling the state constitutional “Indian Education for All” mandate, articulated in Article 10, Section 1(2).18

2005 – Montana Legislature approves Governor Brian Schweitzer’s executive budget request of $1 million for Indian Country economic development to support tribal nations in taking advantage of existing and potential economic opportunities on their reservations. The program is now called the Indian Country Economic Development (ICED) program and remains contingent upon a line-item appropriation.[20]

2006 – Governor Brian Schweitzer grants official state recognition to the Little Shell Tribe,[21] a Declaration that honored the 2003 landmark Montana Supreme Court ruling in Koke v. Little Shell Tribe.[22]

2007 – Montana Legislature passes Senate Bill 173, sponsored by Senator Carol Juneau, to make the State Tribal Economic Development (STED) Commission permanent.[23]

2009 – Montana Legislature passes House Bill 158, sponsored by Representative Shannon Augare, to allow tribal governments to access all economic development grants and loans available under the Big Sky Economic Development Trust Fund, created in 2005.[24]

2009 – Montana Legislature passes House Bill 193, sponsored by Representative Shannon Augare, to change the Coordinator of Indian Affairs title to Director of Indian Affairs, making the position commensurate with other positions in the Governor’s cabinet.[25]

2011 - Montana Legislature passes Senate Bill 412, sponsored by Senator Shannon Augare, to put in place a five-year property tax exemption for tribally owned fee land with pending trust status.[26]

2013 – Montana Legislature passes Senate Bill 342, sponsored by Senator Jonathan Windy Boy and codified as MCA 20-9-537, to provide $2 million for the Montana Indian Language Preservation Pilot Program, to preserve and protect tribal languages for current and future generations.[27]

2014 – Governor Steve Bullock launches the Main Street Montana in Indian Country initiative to work with tribal governments to increase educational and workforce development opportunities, develop reservation infrastructure, increase access to capital, and promote economic growth on reservations.[28]

2015 – Montana Legislature passes House Bill 559, sponsored by Representative George Kipp III, to appropriate an additional $1.5 million to continue the accomplishments of the Montana Indian Language Program into the 2017 biennium.[29]

2015 – Montana Legislature passes Senate Bill 307, sponsored by Senator Sharon Stewart-Peregoy, to require the state to recognize tribal business entities organized under the laws of a federally recognized tribal nation in Montana.[30]

2015 - Governor Steve Bullock creates the Office of American Indian Health to collaborate closely with tribal nations to address health disparities among the American Indian population in Montana and bring about health equity.[31]

2017 - Montana Legislature passes Senate Bill 319, sponsored by Senator Jen Gross, to prevent a state agency or local government from prohibiting an individual from wearing traditional tribal regalia or objects of cultural significance at certain public events, including graduation ceremonies.[32]

2019 - Montana Legislature passes House Bill 21, sponsored by Representative Rae Peppers, to authorize the Department of Justice to assist with the investigation of all missing persons cases and to require the employment of a missing persons specialist within the department.[33]

2019 - Montana Legislature passes House Bill 632, sponsored by Representative Jade Bahr, to require the Department of Commerce to publish an updated decennial report on the economic contributions and impacts to Montana of reservations.[34]

2021 – Montana Legislature passes House Bill 35, sponsored by Representative Sharon Peregoy, to establish a missing indigenous persons review commission.[35]

Conclusion

Although contentious at times, the relationship between the state of Montana and tribal nations has improved significantly over the years. The presence of American Indians in key positions in state government and both chambers of the state Legislature has led to these improvements, along with the continued engagement of American Indians in educating state government officials about tribal communities, cultures, and history. To ensure good relationships with tribal nations and fair representation in the Montana state legislature, the Districting and Apportionment Commission must choose maps that follow what is outlined in the Voting Rights Act and uphold the Montana Constitution in protecting a citizen’s political rights to representation.

MBPC is a nonprofit organization focused on providing credible and timely research and analysis on budget, tax, and economic issues that impact low- and moderate-income Montana families.