This report is part of an ongoing project that introduces readers to foundational topics in Indian Country. Other policy basics in this series cover Tribal sovereignty, citizenship, jurisdiction, and taxation. This report focuses on land.

Approximately 56 million acres of land are held in trust by the United States for various Tribes and individuals.[1] Just like a state has different types of lands within its boundaries — including federal, state trust, and private — the same is true for Indian Country. This report discusses multiple land types, the harmful consequences of past policies, and solutions to past wrongs.

What Is Indian Country?

The term Indian Country holds two meanings. First, it refers generally to Tribal governments, communities, cultures, and peoples. The second meaning is the focus of this report. Indian Country is a legal term for the area over which the federal government and Tribal Nations exercise primary jurisdiction.[2] It includes:

The “rights-of-way” term refers to highways, railroads, power lines, and pipelines that run through a reservation. All land within a reservation is under the jurisdiction of the federal government. Reservation land can be held by the U.S. Government in trust for an Indian Tribe, owned outright by the Tribe, privately owned by a nonmember of the relevant Tribe, or have other ownership. All such land is reservation land and thus “Indian Country.” Land owned by non-Indians and towns incorporated by non-Indians when located within the boundaries of a reservation is Indian Country. Indian Country is where Tribal sovereignty is strongest and state authority is most limited.[3]

A reservation is an area of land reserved for a Tribal Nation as permanent homelands under a treaty or other agreement with the United States, executive order, or federal statute or administrative action. The federal government holds title to the land in trust on behalf of the Tribal Nation. Reservations are generally exempt from state jurisdiction except when Congress expressly authorizes such jurisdiction.[4]

Dependent Indian communities, such as New Mexico Pueblos, are neither reservations nor allotments; however, they are similar in concept.[5] Dependent Indian communities must meet two basic requirements. First, the federal government must have set aside the land for the use of American Indians as Indian land. Second, the federal government must exercise some control or oversight of these lands for Indian purposes.[6]

Allotted trust lands are held in trust by the federal government for American Indians. For example, a 1904 Congressional act resulted in allotments of formerly public lands in Montana to individual citizens of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa.[7]

The Policy of Allotment

Before European settlers arrived in what is today the United States, Indigenous peoples and nations inhabited these lands. When European settlers arrived on the East Coast and expanded westward, Tribal Nations, as sovereigns, entered treaties with the federal government to cede control of vast territories in exchange for the continued inherent right of self-governance, reservations as permanent homelands and federal assistance and provisions, such as health care and education, in perpetuity.

However, the federal government reneged on its obligations. In response to growing settler demand for reservation lands and the assimilation of American Indians into non-Indian society, Congress passed the General Allotment Act of 1887, beginning the allotment and assimilation period.[8] Allotment involved Congress dividing communally held reservation lands into individual parcels without Tribal consent. The federal government then allocated to each Tribal citizen or household an allotment and sold “surplus” parcels to non-Indian settlers, most often without the consent of or compensating Tribal nations. During the Allotment and Assimilation Era, the federal government sought to eliminate Tribal sovereignty, abolish reservations, and assimilate American Indians into non-Indian society.[9]

Between 1887 and 1934, allotment took from Tribal Nations more than 90 million acres, or nearly two-thirds, of all reservation lands — an amount roughly the size of present-day Montana.

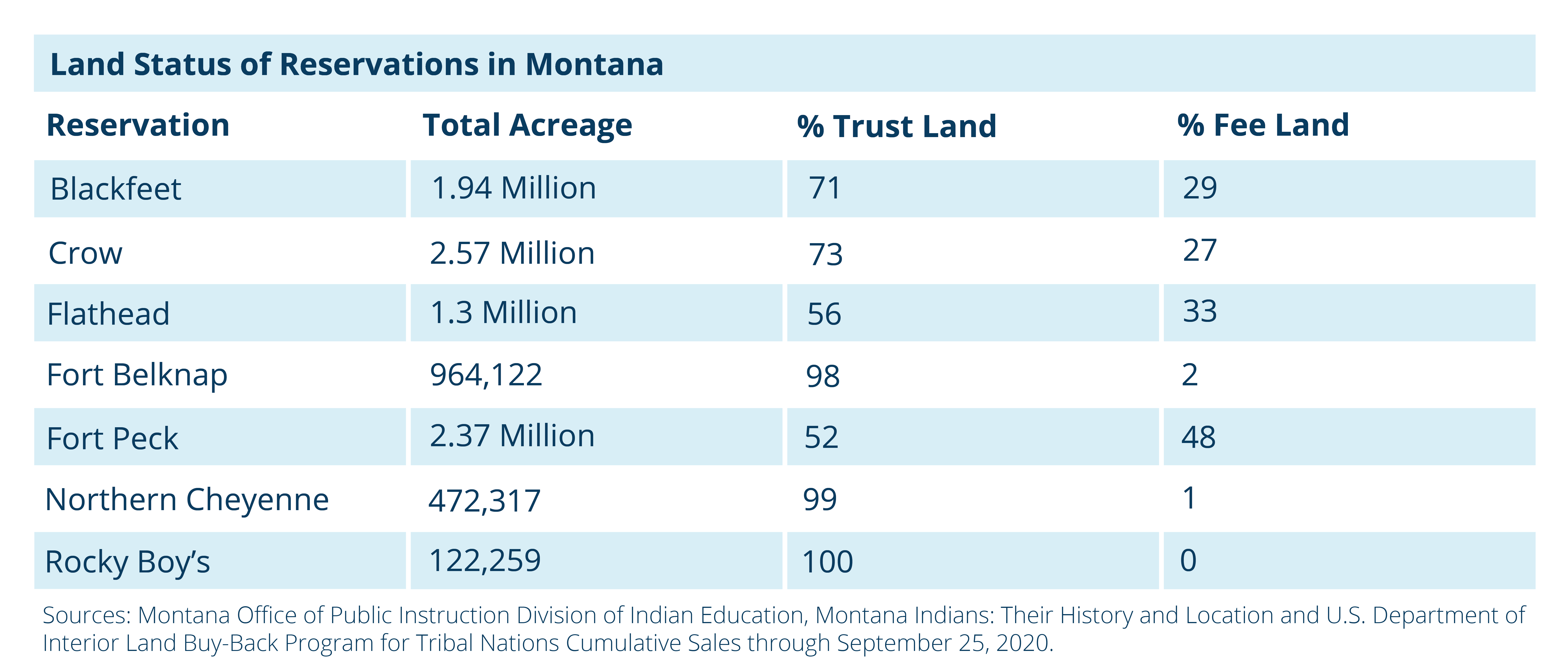

Reservation lands are now a patchwork pattern of ownership and land status, with reservation lands in Montana generally falling into one of two types of status: trust or fee.

Trust land is held in trust by the federal government and includes land collectively owned by a Tribal Nation and allotments to Tribal citizens. Trust land is exempt from property taxes.[10] To help offset the loss of property taxes that support local public schools, the federal Impact Aid Program, also known as Title VII Funds, assists school districts located on or near reservations.[11]

Fee land is generally private property and can be owned by American Indians and non-Indians. State and local taxing jurisdictions may assess property taxes on Tribal-owned fee land.[12] Tribes cannot assess property taxes on reservation fee land and for reservations such as Fort Peck, where more than half the reservation is fee land, this inability equates to a sizable loss of potential revenue for Tribes.

The amount of fee and trust lands varies by reservation. The Rocky Boy’s Reservation is the only reservation in Montana that did not undergo allotment. Of the allotted reservations, much of the allotted lands passed out of Tribal control.[13]

Contemporary Issues of Allotment

As intended, allotment hurt Tribal governments, economies, cultures, and the overall well-being of American Indians. Although the allotment period ended in 1934, its legacy lives on today. The following sections discuss several issues related to that legacy.

Checkerboarding refers to the checkerboard-like pattern of various land types and ownerships, including by non-Indians, of reservation lands. This pattern of scattered, fractionated, and intermixed land ownership often makes reservation land bases less usable for agriculture and other forms of economic development that require adjoining tracts of land.[14]

Checkerboarding also creates jurisdictional challenges, as different governing authorities, including state, county, federal, and Tribal, claim authority to regulate, tax, or carry out various activities within reservation boundaries. Jurisdictional matters on checkerboard lands demand a high level of coordination and the development of cooperative agreements between different jurisdictions.

Hunting and fishing regulations within the exterior boundaries of a reservation often become a topic of contention between Tribes and some non-Indian fee-land owners in Montana. The Fish & Wildlife Commission “has, by rule, closed all lands within the exterior boundaries of Montana’s Indian Reservations to the hunting of game animals with the use of state licenses unless provided for in a cooperative agreement between the Tribal Government and the State of Montana. Currently, no cooperative agreements exist between Fish Wildlife and Parks (FWP) and any of the Tribal Governments in Montana, and as such, the season for the hunting of game animals by nonmembers with a state license is closed.”[15] Some reservations may offer Tribal licenses to non-members looking for game animal hunting opportunities. Court rulings have held that the state's big game hunting closure to non-Tribal members on Indian reservations does not violate constitutional guarantees of equal protection and that the state's big game hunting closure to non-Tribal members on Indian reservations is not an unlawful exercise of the powers of the Commission.[16],[17]

Tribal leaders view the rule as recognizing treaty rights meant to protect big game populations on reservation lands, lands that were never meant to be opened to ownership by non-Indians, to begin with.[18] Tribes as a group have a hunting right, protected by treaties and implicitly retained when they were not addressed by treaties.[19] Each Tribe’s governance process determines who is allowed to exercise it.

Authority over Tribal lands is critical to Tribal Nations to exercise self-governance and self-determination, or Tribal sovereignty.[20] Because allotment has opened reservation lands to non-Tribal jurisdictions, said jurisdictions often conflict with Tribal interests and sovereignty, making it difficult for Tribal Nations to assert their regulatory and legal control. Tribal taxation authority provides one example. In court, state and local governments have successfully challenged Tribal governments’ once-exclusive right to levy taxes within their reservation boundaries to the point that Tribal taxation authority is greatly diminished today.[21]

Due to forced allotment of many reservations, fee land represents a significant share of land on four of the seven reservations. As established, even when Tribal-owned, fee land is subject to state and local property taxes. This is an inconsistent treatment of government-owned property. In Montana, property that is owned by federal, state, and local governments receives an automatic property tax exemption,[22] as consistent with the Montana Constitution.[23] However, the Montana Constitution also declares that all lands owned or held by an American Indian or Tribal Nation remain under the jurisdiction and control of the U.S. Congress.[24]

Righting the Wrongs of Allotment

In 1934, Congress ended the policy of allotment when it passed the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA). Under the IRA, Tribal Nations and the federal government can return fee land to trust status.[25] These fee-to-trust transfers benefit Tribal communities. First, trust acquisitions serve to promote Tribal sovereignty and self-determination. These acquisitions also provide Tribal Nations with the ability to enhance housing options for their citizens, more flexibly negotiate leases, develop Tribal economies, and identify natural resource development and commerce opportunities.

In 2011, the Montana Legislature passed Senate Bill (SB) 412 to create a five-year property tax exemption for Tribal-owned fee lands when those lands have a trust application pending with the federal government.[26] SB 412 facilitates trust acquisitions by allowing Tribal Nations to exclusively direct resources to the process. Although, as recently as the 2019 legislative session, the Legislature attempted and failed to repeal this exemption.[27] In 2021 the Montana Legislature passed SB 214 allowing counties to recapture property taxes if the fee-to-trust application did not go through within five years.[28]

The fee-to-trust application process is often a lengthy (and costly) multi-step federal process for Tribes, sometimes taking longer than the SB 412 five-year property tax exemption law allows for. By comparison, trust-to-fee transfers take just 30 days.[29] Unfortunately, many local governments oppose Tribal Land into Trust applications, in part, on the argument for losses in property taxes due to the existence of newly nontaxable Federal lands within their counties.[30] For other federal lands the Dept. of Interior (DOI) holds title to, Congress provides Payments in Lieu of Taxes (PILT) to offset these losses. However, DOI does not provide PILT payments for Tribal lands it holds title to. The federal government should eliminate this discriminatory practice that holds back the progress of Tribal governments and, ultimately, results in less access to federal programs designed to improve the lives of Indian Country when Tribal land is held in trust.

Also, despite the time and resources that Tribal communities put into the fee-to-trust process, state and local governments and interested parties are still each given 30 days to appeal the transfer once the Bureau of Indian Affairs makes its decision available to those parties.[31]

The Montana legislature initiated a step towards honoring Tribal sovereignty with SB 412 but took a step back with SB 214. Montana could further promote the government-to-government relationship and the process by which Tribal Nations can restore Tribal lands. For example, the 2013 Idaho Legislature overwhelmingly voted in favor of all Tribal-owned property within reservation boundaries being exempted from property taxes.[32] The stated purpose of the Idaho law is to treat all government properties in the state consistently.[33] The fiscal note projected no fiscal impact to state and local governments.

Tribal communities play an essential role in moving Montana forward by growing our shared economies for our shared communities and by providing essential government programs, services, and functions that benefit Montanans. Land issues in Indian Country today are a legacy of anti-Indian policies of the past that sought to undermine Tribal sovereignty and terminate reservations. Montana legislators must keep in mind how land impacts other policy issues.

MBPC is a nonprofit organization focused on providing credible and timely research and analysis on budget, tax, and economic issues that impact low- and moderate-income Montana families.