Finding and affording child care is challenging across Montana. Many families face severely limited options for child care and ultimately pay high costs when they do find care. These challenges are not unique to Montana. Families across the country grapple with finding and affording child care. In 2023, Montana policymakers committed additional state resources to support child care providers and families. Ongoing support and improvements are still needed to build a child care system that works for families, providers, early childhood educators, and Montana’s broader economy.

Current Child Care Supply Falls Short of the Demand from Working Families

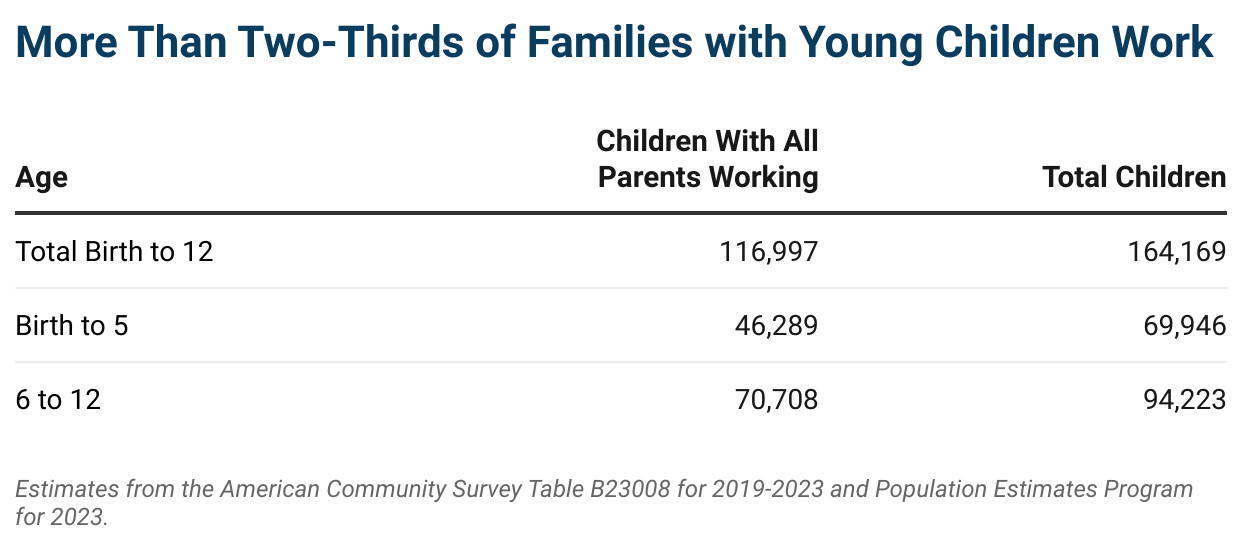

In 2024, 1,230 programs were licensed or registered with the state, providing slots for 26,012 children. [1], [2] Child care capacity has increased by about 3,500 slots or 15 percent in the last five years. However, the current capacity still only meets roughly half of the estimated demand from working families.[3] Four counties still had no regulated child care programs, and 25 of 56 counties were classified as child care deserts (meeting less than a third of the estimated demand from working families).

Finding an infant or toddler slot is incredibly difficult, with only 6,085 slots set aside statewide for this age group, meeting only 41 percent of the demand. [4],[5] For older, school-age youth, care is also limited. The state does not regulate most school-age programs due to the lack of a licensing framework for out-of-school time programs. For every school-age youth in an afterschool program, four more are waiting to get in.[6] Child care for children during the evening, overnight, or on weekends is also scarce. In a survey of over half of regulated providers, less than 7 percent of home-based providers and only 2 percent of centers were open on weekends.[7]

Child care supply and demand is typically reflected as a simple equation – the number of slots should equal the number of children needing care. The reality of finding child care for families is much more nuanced and complicated. Simply having enough child care slots does not factor in other needs and preferences. For example, families often desire a program that reflects their culture and values. In a survey of regulated programs, the majority reported having a waiting list (50 percent of home-based providers and 65 percent of centers), another indication that the demand for programs remains high.[7]

Limited child care availability is significant for working families and Montana businesses. Without enough child care options, parents must make difficult decisions about how and whether to pursue work or education opportunities. Across the state, 40 percent of businesses report difficulty recruiting or retaining qualified workers due to the lack of child care.[8] The lack of child care results in $55 million in lost business revenue annually, showing how child care shortages impact us all in Montana.[8]

Child Care Makes Up a Big Expense for Families, Yet Child Care Workers Earn Low Wages

For families that do find child care, the cost can still keep the care out of reach. The cost for full-time child care varies based on age, the type of facility, and geographic location within Montana. Parents pay, on average, $11,700 per year for center-based care and $9,100 per year for family-based child care.[9] This means child care costs more than in-state tuition at Montana State University ($8,460 per year).[10] Data from the most recent market rate survey captures the variation in cost across the state, with the median annual cost for infant care at a center ranging from $13,800 in Region 4 (Broadwater, Gallatin, Jefferson, Lewis & Clark, Meagher, and Park counties) to $9,000 in Region 3 (Beaverhead, Deer Lodge, Granite, Madison, Powell, and Silver Bow counties).[7],[11]

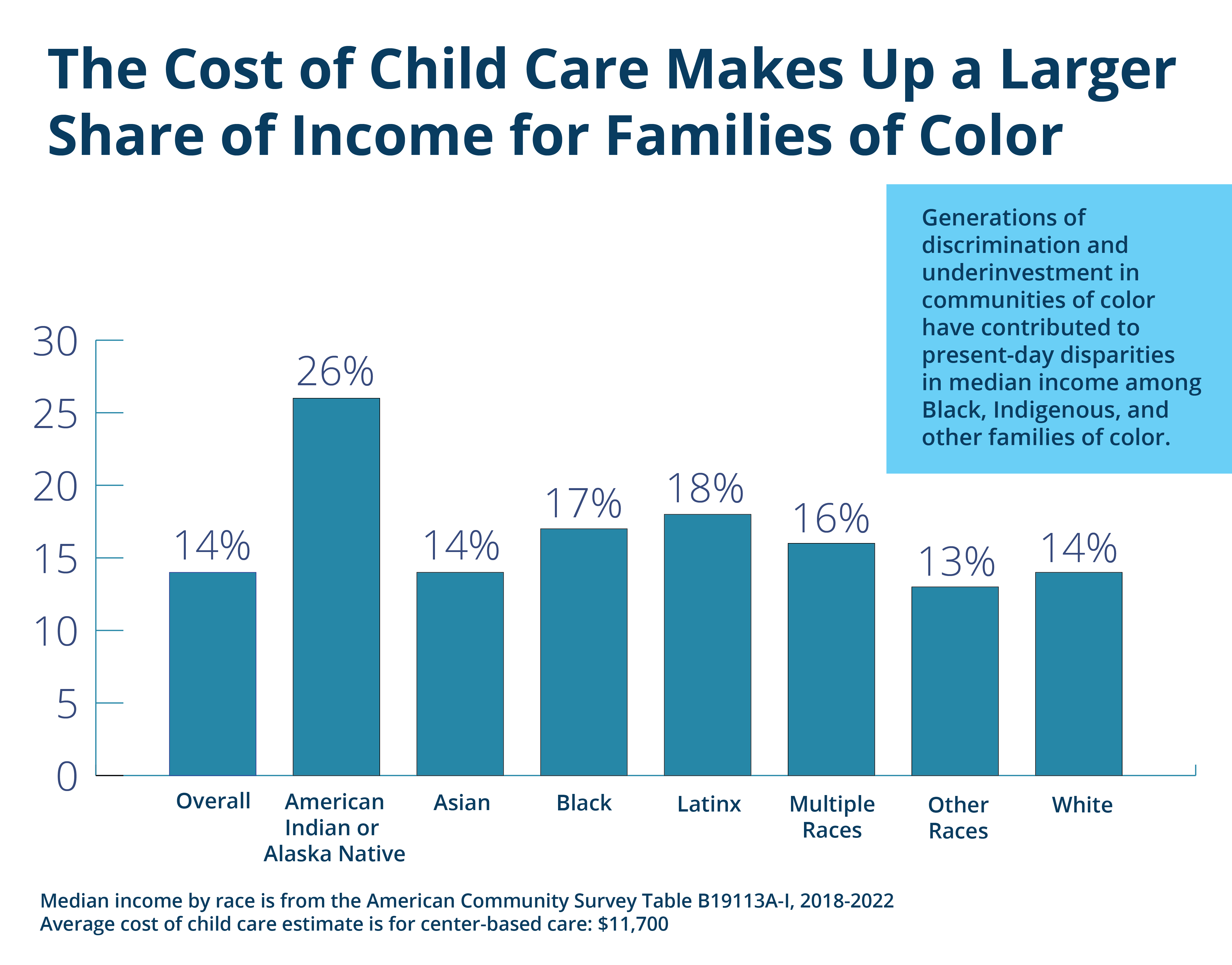

Affordable child care is essential for advancing racial and economic equity and empowering families to pursue education, training, and careers. Despite generations of systemic barriers, Black, Indigenous, and other communities of color have shown resilience, though income disparities persist. As a result, child care is disproportionately more unaffordable for families of color. The average cost estimate for center-based care ($11,700) makes up 14 percent of a typical family’s income.[12] The cost of child care for Black, Indigenous, and multiracial families makes up a larger share of their income, putting child care further out of reach for these families. When child care is less accessible for families of color, it perpetuates the cycle of having limited opportunities to work or continue their education.

Affordable child care is essential for advancing racial and economic equity and empowering families to pursue education, training, and careers. Despite generations of systemic barriers, Black, Indigenous, and other communities of color have shown resilience, though income disparities persist. As a result, child care is disproportionately more unaffordable for families of color. The average cost estimate for center-based care ($11,700) makes up 14 percent of a typical family’s income.[12] The cost of child care for Black, Indigenous, and multiracial families makes up a larger share of their income, putting child care further out of reach for these families. When child care is less accessible for families of color, it perpetuates the cycle of having limited opportunities to work or continue their education.

While child care makes up a big expense for families, child care workers make low wages despite the value of their essential work. The reality of today’s child care profession has been shaped by decades of policies and public perception that devalued the role of caring for young children. For example, the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 excluded domestic, agricultural, and service occupations.[13] This exclusion reflects a policy decision that overlooked the value of caregiving work, despite the expertise and contributions of women, particularly BIPOC women, who have long been leaders in domestic and caregiving roles. There are centuries of different examples of policies that set a precedent for undervaluing caregiving as a skilled and essential role. This legacy of policies shapes the present-day reality of an underpaid and undervalued child care workforce.

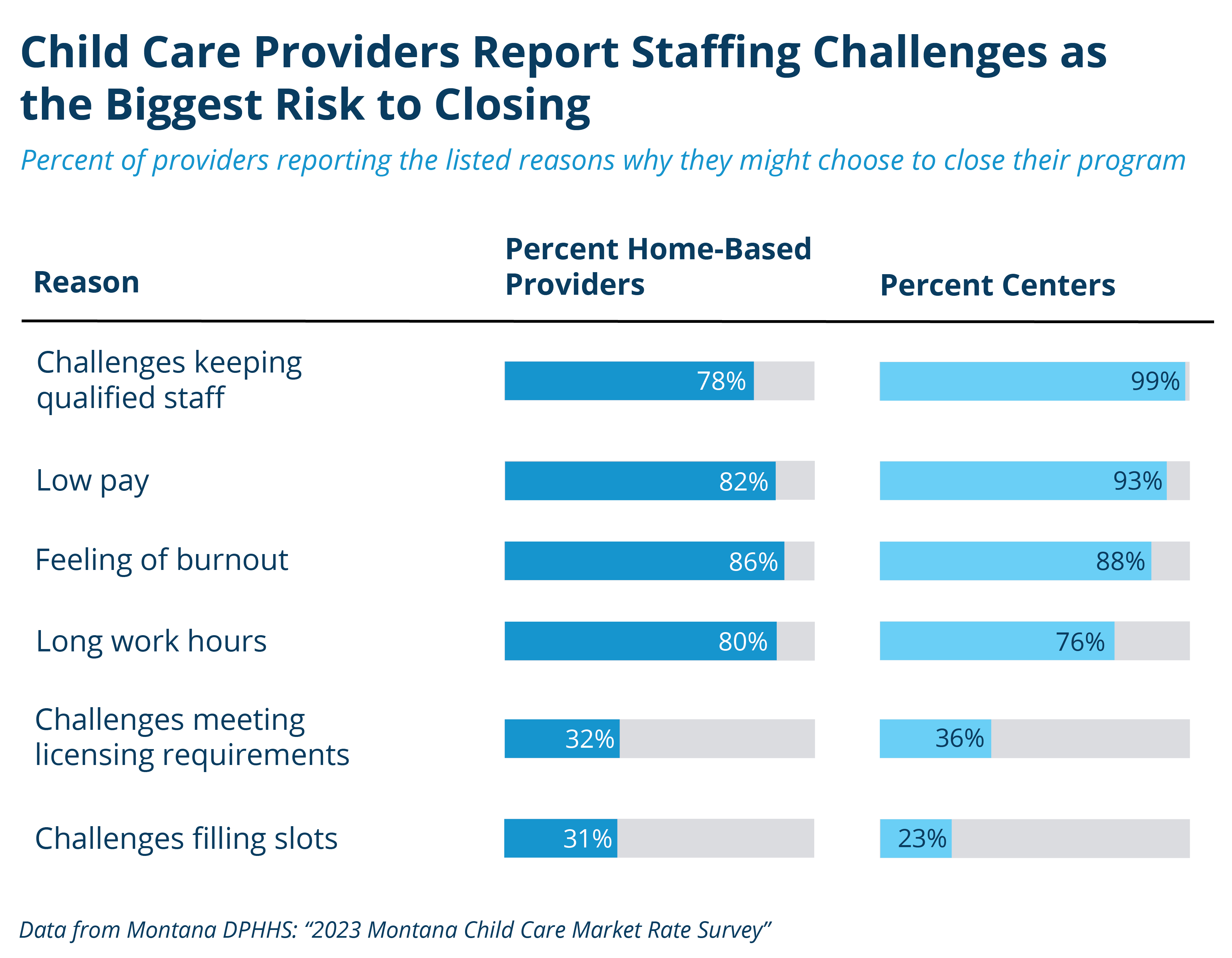

Child care programs are left to figure out how to balance the true cost of  providing high-quality care with what parents can afford. This often means providers struggle to offer competitive pay and benefits to their staff. In 2023, the median wage for a child care worker in Montana was $13.99 per hour, and 13 percent of early educators in Montana live below the poverty level. [14],[15] Low wages for child care workers lead to staff turnover and shortages, making it challenging for child care businesses to retain workers and remain open. In a survey of over half of regulated providers, the majority (75 percent) reported that staffing challenges might lead them to close their programs, including staff burnout, long work hours, low pay, and difficulty retaining staff.[7]

providing high-quality care with what parents can afford. This often means providers struggle to offer competitive pay and benefits to their staff. In 2023, the median wage for a child care worker in Montana was $13.99 per hour, and 13 percent of early educators in Montana live below the poverty level. [14],[15] Low wages for child care workers lead to staff turnover and shortages, making it challenging for child care businesses to retain workers and remain open. In a survey of over half of regulated providers, the majority (75 percent) reported that staffing challenges might lead them to close their programs, including staff burnout, long work hours, low pay, and difficulty retaining staff.[7]

Best Beginnings Is an Opportunity to Support Families and Providers

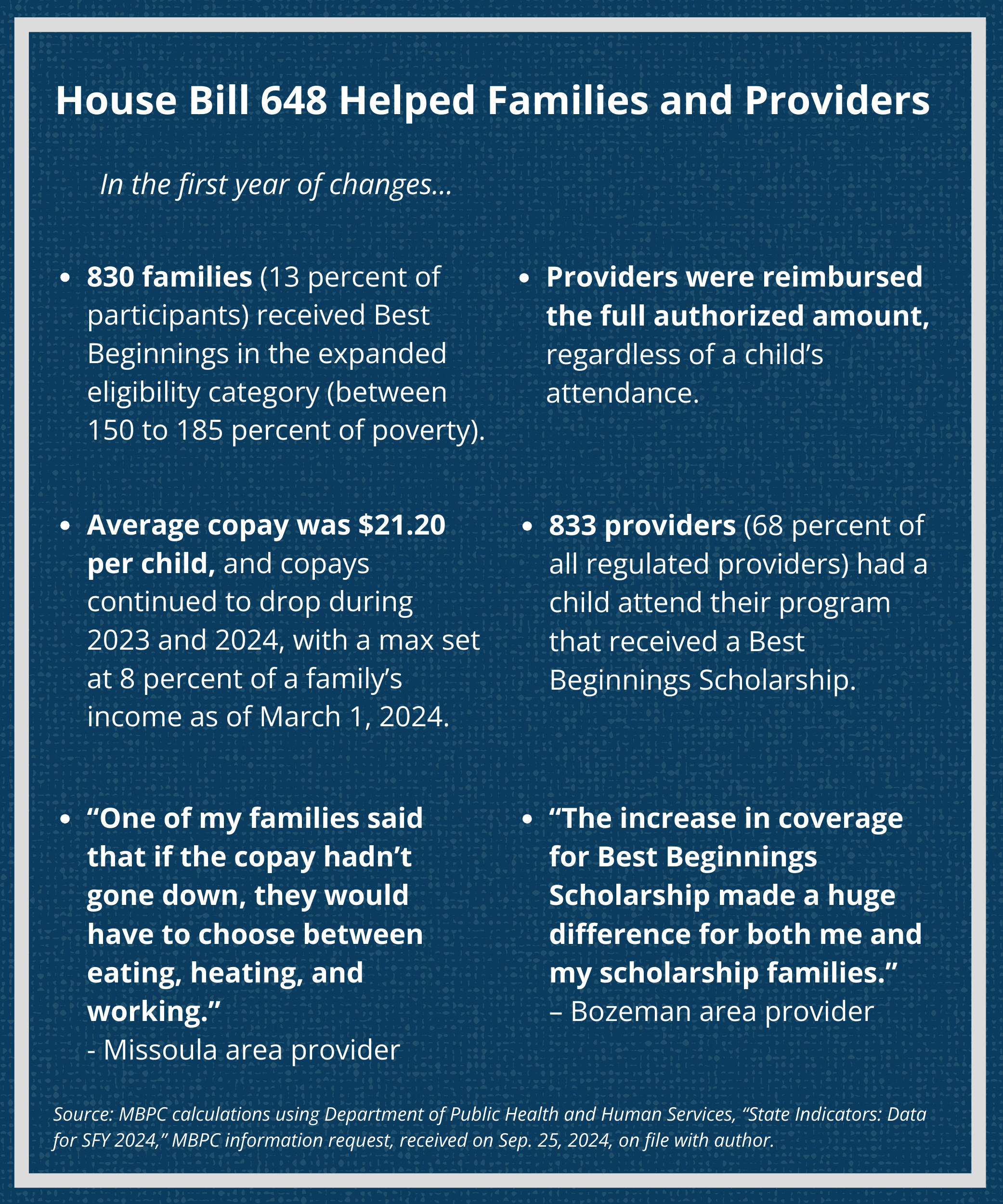

The Best Beginnings program is a key opportunity to improve Montana’s child care system. Best Beginnings is primarily funded through a federal block grant, with most funds going directly to providers to cover the cost of child care for families living on low incomes. The same block grant supports child care regulation, promotes program quality, and provides services to help support providers. In addition to federal funding, the state provides matching dollars and committed an additional $7 million per year as part of changes from House Bill 648.[16]

Child care assistance, like the Best Beginnings program, looks different across states, with a lot of flexibility given to state policymakers to set eligibility requirements, copayment amounts, and other participation details. In Montana, a family is eligible for Best Beginnings if they:[17]

1. Have a child, age 12 or younger, or an older child with special needs;

2. Need child care to work, attend school, or participate in job training activities;

3. Earn at or below 185 percent of the federal poverty level, or less than about $47,700 per year for a family of three;[18] and

4. Meet child support requirements, if applicable.

Families receiving Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) are also  eligible for Best Beginnings. Children in foster care are eligible for Best Beginnings through age 17, even without their family meeting the income or work criteria. To access the Best Beginnings program, a child must attend a regulated childcare program, and the provider receives a reimbursement from the state for the care provided. Some families pay a copay that is less than 8 percent of a family’s income.[18] For example, a family of three with an income at the highest eligibility level pays a $318 copay each month.

eligible for Best Beginnings. Children in foster care are eligible for Best Beginnings through age 17, even without their family meeting the income or work criteria. To access the Best Beginnings program, a child must attend a regulated childcare program, and the provider receives a reimbursement from the state for the care provided. Some families pay a copay that is less than 8 percent of a family’s income.[18] For example, a family of three with an income at the highest eligibility level pays a $318 copay each month.

The income guidelines for eligibility have shifted over time in Montana, with eligibility currently set at 185 percent of the federal poverty level (after House Bill 648 directed an increase from 150 percent).[19] A family already receiving Best Beginnings can remain on the program up to 200 percent of the federal poverty level (or $51,636 for a family of three) for a 12-month window after their initial approval; this graduated eligibility lessens the cliff a family faces with small boosts in wages.[18] Federal guidelines limit the use of block grant funds for families above 85 percent of the state median income, which is about 260 percent of the federal poverty level in Montana.[20],[21] North Dakota (75 percent of the state median income or about 280 percent of the poverty level) and South Dakota (209 percent of poverty) both have eligibility set higher than Montana.[22],[23] Ultimately, families above Montana’s current eligibility still struggle to afford child care. For example, a family of three making 85 percent of the state median income (about $68,000 per year) pays 17 percent of their income for the average cost of infant care at a center ($11,700).[9]

Similar to eligibility, copays have also shifted over time in Montana. Copays in the last few years have ranged from a max of $10 during certain time periods up to 13 percent of a family’s income. As of March 2024, copays are no more than 8 percent of a family’s income.[18] New federal guidelines for child care assistance require states to cap copays at 7 percent of a family’s income, with Montana requesting a waiver for two years to meet this new requirement.[24]

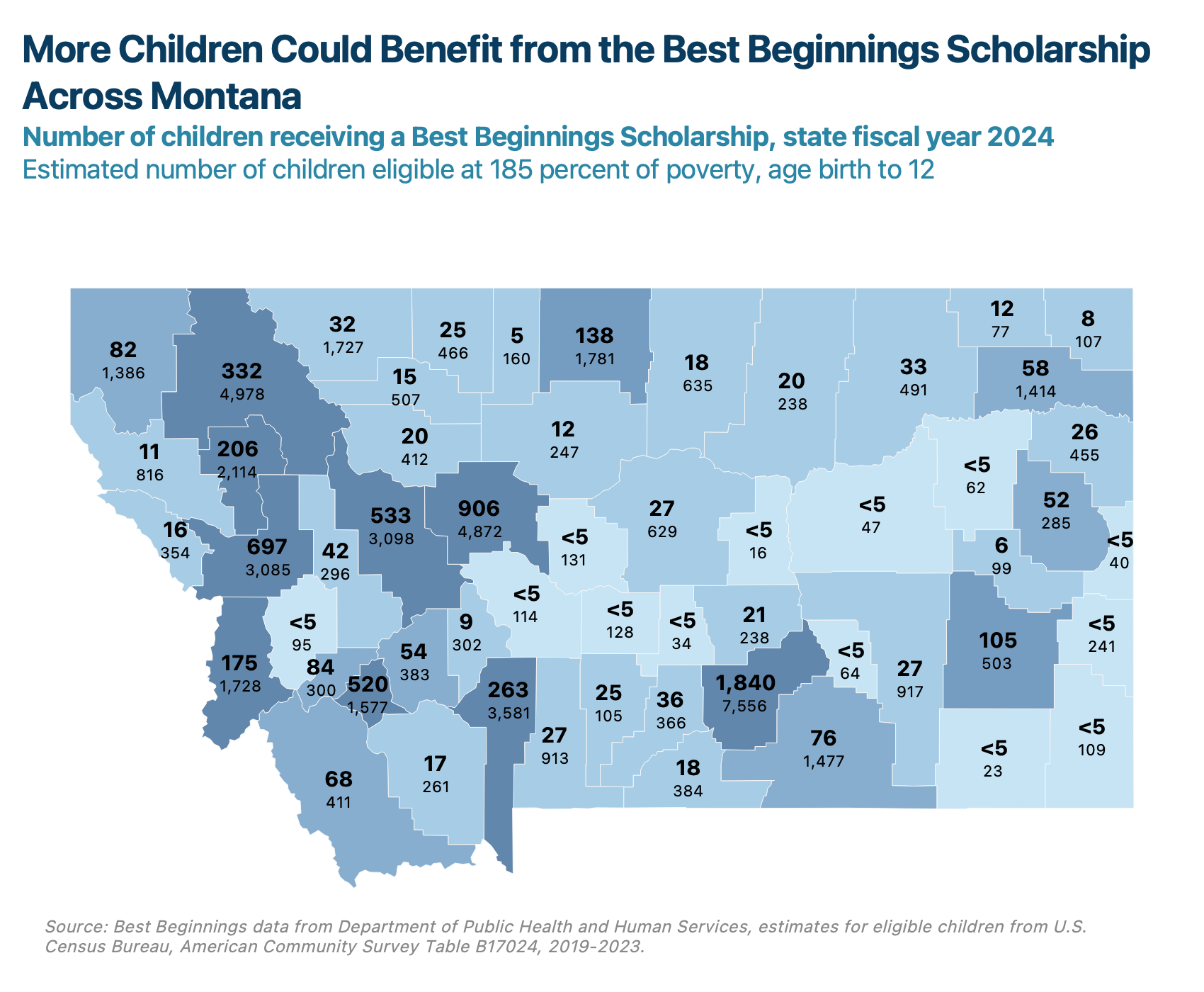

In the state fiscal year 2024, 6,554 children participated in Best Beginnings.[25] Many more families are eligible to receive Best Beginnings than participate. Approximately 53,000 children age birth to 12 lived in families below the current income guidelines, yet only 12 percent received child care assistance.[26] Low participation rates for child care assistance are a common trend nationwide. However, Montana falls below the national average of 22 percent.[27] Removing barriers and improving access to Best Beginnings is an important strategy for addressing child care challenges across the state.

Many more families are eligible to receive Best Beginnings than participate. Approximately 53,000 children age birth to 12 lived in families below the current income guidelines, yet only 12 percent received child care assistance.[26] Low participation rates for child care assistance are a common trend nationwide. However, Montana falls below the national average of 22 percent.[27] Removing barriers and improving access to Best Beginnings is an important strategy for addressing child care challenges across the state.

Families face barriers when applying for the Best Beginnings program. Of the 4,380 applications received for Best Beginnings during the state fiscal year 2024, about half were eligible for assistance or still in progress. Of the remaining applications denied, the majority (73 percent) encountered administrative barriers and had missing documentation needed as part of the application. This indicates the state needs a better understanding of the barriers families face in completing their applications timely and accurately and then implementing strategies to minimize those barriers. Of the remaining applications that were denied, the most common reasons included a family being over income (50 percent), eligibility could not be determined even though some documentation was turned in (20 percent), other state eligibility guidelines were unmet like age of child or the minimum work or education hours (12 percent), and failure to meet the child support requirement (7 percent).[28]

Improving the Best Beginnings program is a key strategy to improve the child care system in Montana and help more families access and afford high-quality child care across the state.

Key Strategies Can Help Improve Best Beginnings for Families and Providers

Strategy#1: Reach More Families and Child Care Staff Through the Best Beginnings Program

Expanding eligibility to the maximum federal level (85 percent of the state median income) would benefit more families struggling to afford child care. For example, a family of three at 85 percent of the state median income (about $68,000 per year) is not currently eligible but spends 17 percent of their income on infant child care at a center or 13 percent of infant child care in a home-based program.[9] Expanding eligibility to all child care staff, regardless of income, is another strategy to reach more families struggling to pay for child care. This eligibility expansion also serves as a recruitment and retention tool by boosting benefits for child care workers with young children. Three states (Iowa, Kentucky, and Maine) invested state dollars to expand eligibility to child care staff regardless of income.[29] Many other states have expanded eligibility for child care workers up to the federal maximum, similar to Montana’s program that provides eligibility up to 250 percent of the poverty level for child care staff.[30]

Strategy #2: Make It Easier for Families to Access Best Beginnings

Removing the child support requirement would allow more families to access Best Beginnings. Montana requires families to cooperate with child support as an eligibility condition, if applicable to the family. Meeting child support guidelines creates more barriers for vulnerable families, including single-parent families and teen parents. States have the flexibility to remove child support enforcement as an eligibility requirement.

Strategy #3: Support Child Care Providers

Restructure the licensing framework to create a category for school-age programs. Having a more inclusive licensing framework benefits both families and providers. School-age programs that become licensed can take advantage of training programs and additional funding opportunities and accept Best Beginnings. Reimburse providers at the maximum state rate for Best Beginnings, regardless of what they charge other families. Currently, providers are reimbursed only up to the amount they charge private-pay families, creating another impossible decision for providers: raise rates for families not eligible for Best Beginnings that struggle to afford the cost or accept a lower rate for their Best Beginnings participants. Federal guidelines encourage paying at the full rate stating that “because child care providers’ price for services reflects what private-pay families enrolling in their programs can afford and not necessarily the (higher) cost of providing services, payment rates are artificially constrained by affordability, particularly in low-income neighborhoods.”[24]

Moving the Needle on Child Care Requires a Growing State Investment

More state investment in child care is needed to significantly shift child care access and affordability in Montana. Continued investment is critical to maintaining the improvements gained in the last two years, and a growing investment is needed to truly move the needle on child care challenges across the state. Other neighboring states have made significant investments to expand child care assistance and support higher pay and benefits for child care workers:

A state investment should accompany policy strategies identified in this report to improve access and affordability of child care in Montana. Without additional state funding, child care businesses and workers will continue to bear the impact of the cost imbalance, earning only poverty-level wages in exchange for the valuable work of caring for children. Montana policymakers who value supporting the youngest Montanans, families, child care providers, and businesses should work together to pass child care funding in 2025 and implement policies to improve child care access and affordability.

[1] KIDS COUNT Data Center, “Regulated Child Care Facilities by STAR Level in Montana,” 2024.

[2] KIDS COUNT Data Center, “Regulated Child Care Capacity by STAR Level in Montana,” 2024.

[3] KIDS COUNT Data Center, “Percent of Children Under Age 6 With All Parents Working that Can Be Served by Regulated Child Care Capacity in Montana,” 2024.

[4] KIDS COUNT Data Center, “Regulated Child Care Capacity for Infants and Toddlers (Age Birth to 1) by STAR Level in Montana,” 2024.

[5] KIDS COUNT Data Center, “Percent of Infants and Toddlers With All Parents Working That Can Be Served By Regulated Child Care in Montana,” 2024.

[6] Afterschool Alliance, “Afterschool in Montana,” accessed on Aug. 5, 2024.

[7] Department of Public Health and Human Services, “2023 Montana Child Care Market Rate Survey: Final Report.”

[8] Watson, A., “Childcare and the Montana Workforce,” Montana Department of Labor & Industry, Jan. 9, 2024.

[9] Child Care Aware of America, “Child Care Affordability in Montana,” accessed on Aug. 5, 2024.

[10] Montana State University, “Estimated Expenses, 2024/2025 Montana State University Undergraduate Cost of Attendance,” accessed on Sep. 16, 2024.

[11] Department of Public Health and Human Services, “Child Care Resource and Referral Agencies and Regions,” accessed on Aug. 5, 2024.

[12] Median family income by race is from table B19113A-B19113I. U.S. Census Bureau, “Median Family Income in the Past 12 Months (in 2022 Inflation-Adjusted Dollars), 2018-2022 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table B19112,” accessed on July 26, 2024.

[13] Lloyd, C., Carlson, J., Barnett, H., Shaw, S., Logan, D., “Mary Pauper: A Historical Exploration of Early Care and Education Compensation, Policy, and Solutions,” Child Trends, Sep. 2021.

[14] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “May 2023 State Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates.”

[15] Population Reference Bureau analysis of U.S. Census Burea, American Community Survey Public Use Microdata Sample, 5-year estimates for 2018-2022, on file with author.

[16] O’Loughlin, H., “HB 648: Bridging the Gap to Childcare,” Montana Budget & Policy Center, June 27, 2023.

[17] Department of Public Health and Human Services, “Child Care Policy Manual,” accessed on Aug. 5, 2024.

[18] Department of Public Health and Human Services, “Montana Best Beginnings Child Care Scholarship Child Care Sliding Fee Scale,” Mar. 1, 2024.

[19] Department of Public Health and Human Services, “Department Updates: Best Beginnings Childcare Subsidies,” presentation to the Children, Families, Health, and Human Services Interim Committee, Mar. 12, 2024.

[20] Congressional Research Service, “The Child Care and Development Block Grant: In Brief,” Nov. 18, 2022.

[21] The State Median Income (SMI) depends on household size. When converting the federal max of 85 percent of SMI to the poverty level, it ranges from 255 percent for a family of six, to 270 percent for a family of two. State Median Income data: The Administration for Children and Families, “State Median Income (SMI) by Household Size for Mandatory Use in LIHWAP for FY 2024 – Households of Size 1 through 6.”

[22] North Dakota Department of Health and Human Services, “Child Care Assistance Program,” accessed on Aug. 5, 2024. As of July 1, 2024 North Dakota changed eligibility to 75 percent of the state median income, down from the max of 85 percent prior. Similar to Montana, converting state median income to poverty ranges from 270 percent to 285 percent of poverty.

[23] South Dakota Department of Social Services, “Am I Eligible for Assistance,” accessed on Aug. 5, 2024.

[24] Administration for Children and Families, “Improving Child Care Access, Affordability, and Stability in the Child Care Development Fund (CCDF),” published Mar. 1, 2024.

[25] KIDS COUNT Data Center, “Children Receiving Best Beginnings Child Care Scholarship in Montana,” 2024.

[26] Eligible children (denominator of percentage) is calculated as the number of children aged birth to 12 based on 2023 population estimates multiplied by the percent of children living below 200 percent of the federal poverty level from table B17024. KIDS COUNT Data Center, “Child Population by Single Year of Age in Montana,” 2023. U.S. Census Bureau, “Age by Ratio of Income to Poverty Level in the Past 12 Months, 2019-2023 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table B17024,” accessed on Aug. 5, 2024.

[27] Chien, N. “Estimates of Child Care Subsidy Eligibility & Receipt for Fiscal Year 2021,” Office of the Assistance Secretary for Planning & Evaluation, Sep. 2022.

[28] MBPC calculations using Department of Public Health and Human Services, “Indicator 8. Number of Best Beginnings applications that were denied,” MBPC information request, received on Sep. 25, 2024, on file with author.

[29] Spinetti, M., “Child Care Subsidies for Child Care Workers,” prenatal-to-3 policy impact center, July 8, 2024, on file with author.

[30] Department of Public Health and Human Services, “Childcare Assistance for Childcare Workers,” on file with author.

[31] North Dakota KIDS COUNT, “2023 Legislative Session: Children’s Well-Being Bills,” Aug. 2023.

[32] Minnesota’s Children’s Cabinet, “2023 Legislative Wins for Children and Families,” accessed on Aug. 5, 2024.

MBPC is a nonprofit organization focused on providing credible and timely research and analysis on budget, tax, and economic issues that impact low- and moderate-income Montana families.