Congress has a chance to begin to dismantle long-standing racial inequities that federal policies helped create by passing Build Back Better (BBB) policies. BBB policies will help families, children, and workers by making child care, housing, tribal colleges, and worker training programs accessible and affordable. We can have a more equitable economic recovery by funding these critical reforms with revenue generated from the wealthiest who continually avoid paying what they owe.

The policies in Build Back Better will make a meaningful difference in narrowing racial disparities and stem the decades-long lack of investments in communities. Throughout our history, state and federal decision makers, who are majority white, have advanced racist and discriminatory policies. The result is Black, Indigenous, and other people of color (BIPOC) are more likely to experience poverty and food insecurity and work in industries with lower wages than white people. Through historic investments in child care, health care, housing, and the caregiving workforce, we address the racial and ethnic inequities built into poverty rates, health coverage, and education.

The Child Tax Credit Lifts Children Out of Poverty

Due to a long history of racist public policies, ongoing settler colonialism, and underinvestment, American Indian Montanans, on average, earn lower incomes than white Montanans.[1] Lower incomes, in addition to discrimination in housing and employment, also result in fewer opportunities for children of color more broadly.[2] The COVID-19 pandemic and economic recession added to these disparities by disproportionately impacting American Indians and other families of color and exacerbating growing inequities.

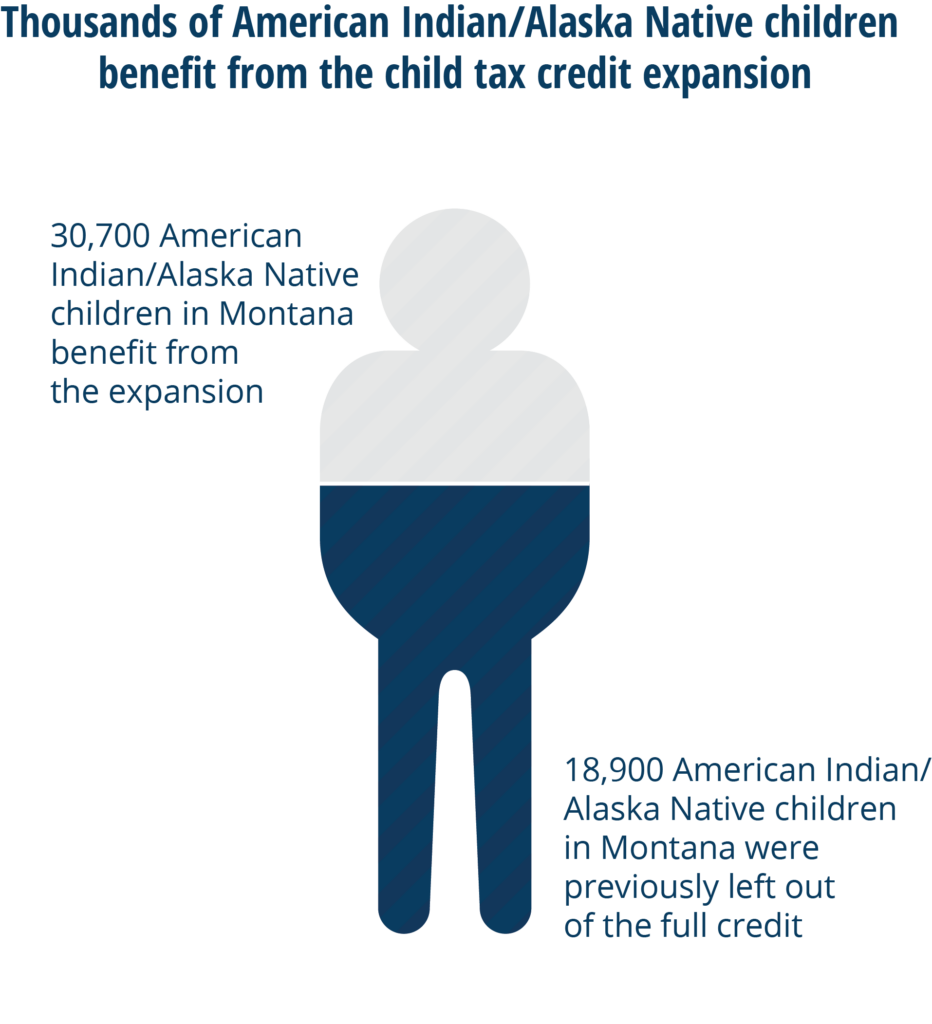

Expanding the child tax credit (CTC) for an additional year and permanently making it fully refundable will reduce childhood poverty and racial inequities. Continuing the CTC expansion will support 209,000 Montana children, of whom 30,700 are American Indian, providing a critical boost in income for things like food, utilities, child care, and housing.[3],[4],[5] The full first year expansion would help lift 45 percent of all Montana children and 59 percent of American Indian/Alaska Native children in Montana out of poverty, compared to before the expansion.

The child tax credit increased from $2,000 to $3,600 per child under six and $3,000 for older children. To qualify for the entire expanded credit, heads of households may earn up to $112,500 or $150,000 for married couples before the credit begins to phase out. The BBB extends the increased credit amounts for one additional year and permanently makes the CTC fully refundable, meaning families will receive the total amount of the CTC, even if they owe less than the credit amount. Without a refundable CTC, one-third of children in Montana do not receive the full benefit of the CTC because their families earn too little.[6]

Child Care and Pre-K Benefit Children, Families, and Care Workers

Due to hundreds of years of the federal government’s underinvestment in education, employment discrimination, settler colonialism, and other systemic barriers, American Indians experience more impediments to employment and difficulty making ends meet than white Montanans. Currently, a lack of child care is a crucial dilemma for many families looking to get back on their feet from the pandemic. Nationally, prior to the pandemic, only 54 percent of American Indian children age five and younger had child care arrangements other than their parents.[7] Even before the pandemic, lack of child care created barriers to work for American Indian families at higher rates than white families, meaning American Indian caretakers more often had to quit their job, decline a job or promotion, or significantly change their job to care for children.[8]

Low wages among child care workers are a racial justice, gender justice, and economic justice issue. Because of employer discrimination, racism, and the perceptions of caregiving responsibilities, women, and women of color specifically, are overrepresented in child care work and are often paid poverty wages. In Montana, there are 11,023 frontline workers in the child care and social services industry, a disproportionately high share of whom are American Indian (8.8 percent), compared to 5.4 percent of all workers.[9] More than eight out of every ten people in this industry are women.

Education does not insulate child care workers from low wages. Many of these workers are highly educated. More than 35 percent have completed a college or advanced degree, and 33 percent have completed some college.[10] Despite these educational levels, a child care worker makes less than half the wage of a Kindergarten teacher, and 37.6 percent of child care workers live on incomes less than 200 percent of the poverty line (an annual income of $34,840 a year for a household of two) compared to 24 percent of all workers.[11],[12]

BBB seeks to improve many of the issues in the child care industry by expanding child care assistance, child care supply, and guaranteeing support for nearly all families in Montana. Eligibility for child care assistance would be phased up over three years, starting with families at 100 percent of the state median income ($54,970 in 2019) and phasing up to 250 percent of the state median income by the third year.[13],[14] In Montana, roughly 63,000 children would become eligible for assistance, which is more than 85 percent of all children. Montana is slated to receive $67 million in 2022, $95 million in 2023, and $118 million in 2024.[15] The program will cap copays for families at 7 percent of family income, and families at lower incomes would not be subject to copays. To receive funding, states must establish a plan to use the federal investment to expand child care assistance, increase supply, and ensure child care professionals are paid living wages. Federal funds cover the entire program in the first three years as states expand their programs and build capacity. After that, the program guarantees child care assistance for all eligible families, with federal funding covering 90 percent of the cost and states matching 10 percent.

In addition, BBB includes funding to states and tribal nations to establish universal preschool for 3 and 4-year-old children. States must establish a hybrid delivery system, allowing licensed child care providers, Head Starts, and school districts to provide preschool slots in their communities. States must ensure preschool teachers receive a living wage comparable to what elementary school teachers earn.

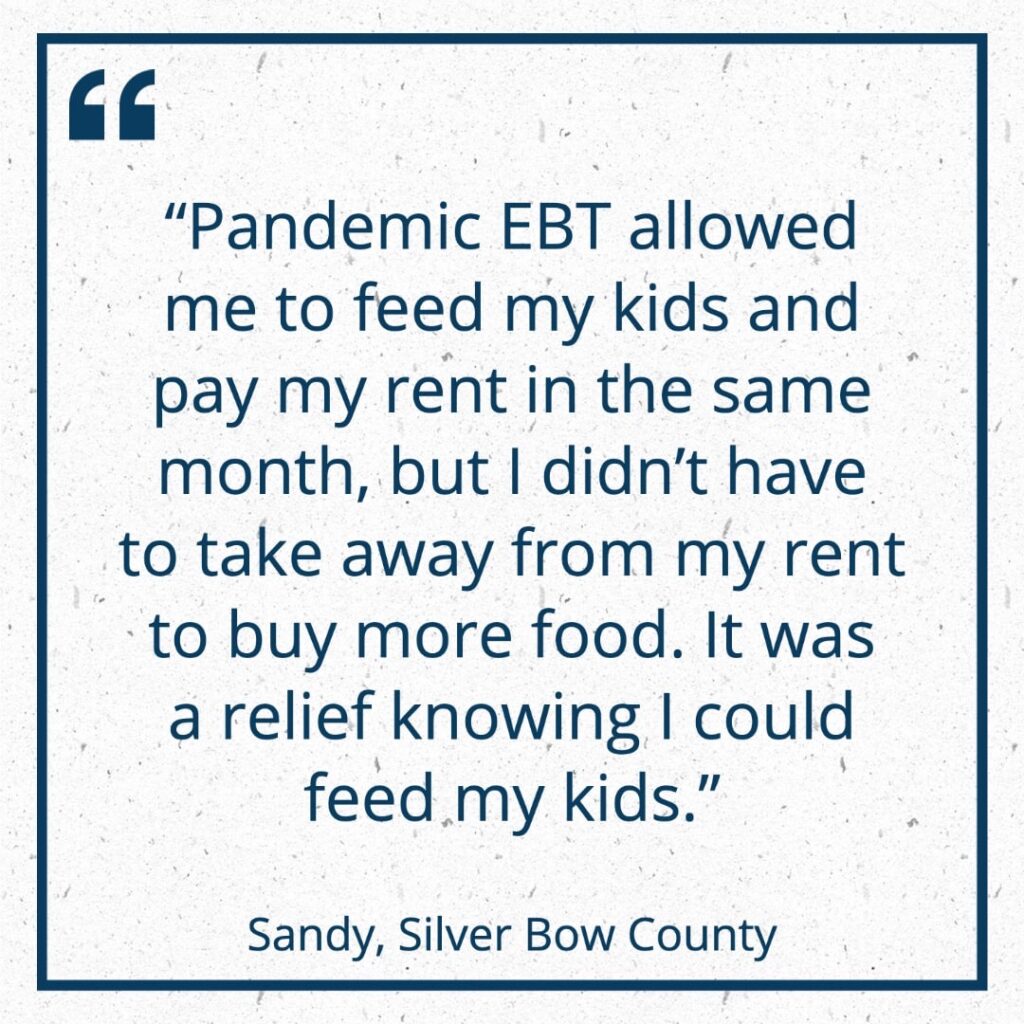

Provide Healthy Food for Children

All families should have enough nutritious, culturally appropriate food. However, one in 10 Montanans do not have reliable access to healthy, affordable food.[16]Food insecurity is often connected to low incomes, which are influenced employment discrimination, barriers to accessing education, and other structural racism.

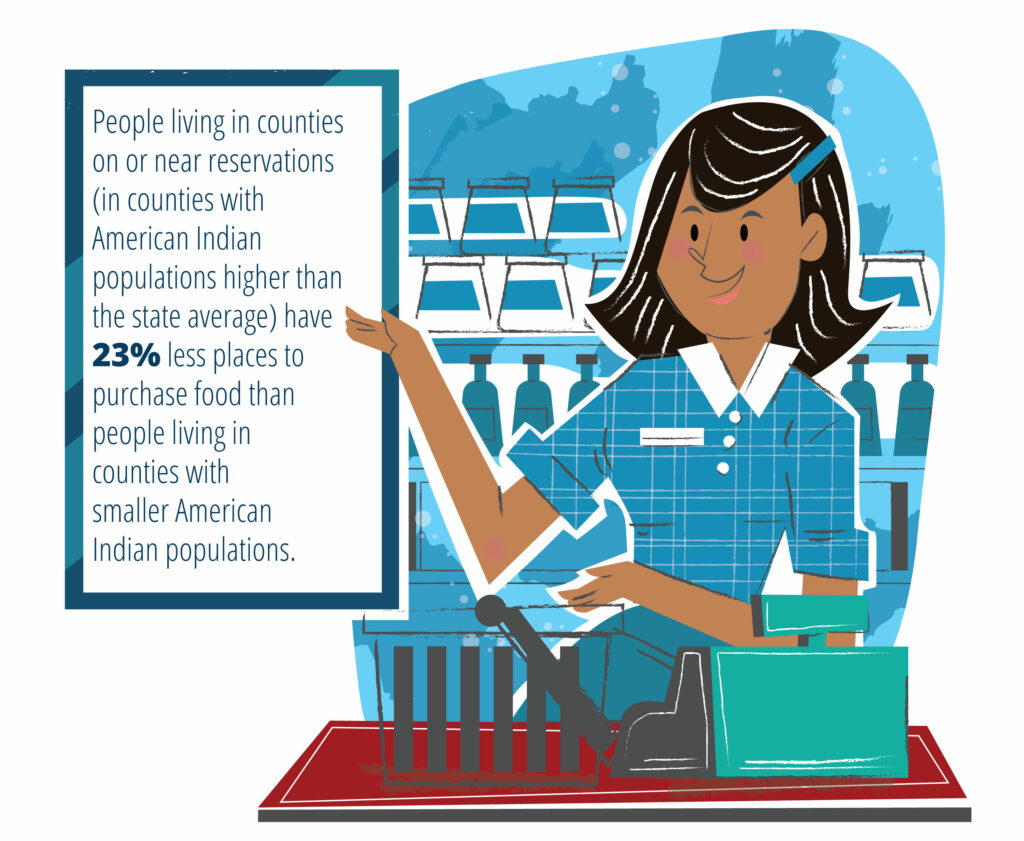

Food insecurity is even more of a concern for American Indians, who often see higher costs and less access to food and experience lower incomes. This is partly the result of a settler-colonial agenda that displaced and isolated tribal communities away from traditional food sources. In many instances, tribal nations today face significant barriers to economic development and subsequently face limited access to grocery stores and higher costs of food.[17] People of color other than American Indians also experience increased food insecurity rates, and these long-standing racial and ethnic disparities in food insecurity widened during the pandemic.[18] While the share of white families with children experiencing food insecurity declined in 2020, the share of Black and Latinx families with children experiencing food insecurity rose to be more than twice the rate of white families.[19]

More than 65,000 Montana children who receive free or reduced-price school meals will also receive summer grocery supports to address food insecurity when children are not in school.[20] BBB will expand access to free school meals during the school year for 11,000 Montana children. It provides increased funding to improve the quality of food served and allows for fresh, local, regional, and culturally appropriate food. These changes improve health and prospects for success for children who currently live without food security.[21]

Reduce Racial Disparities and Improves Stability of Housing

For so many families, safe and stable housing is out of reach. This issue is heightened for families of color due to a long history of housing segregation, redlining, and disinvestment in neighborhoods, along with ongoing discrimination, overcrowding, and evictions that force many families into unstable housing or homelessness.[22] Nationwide, nearly 8 million children in families with low incomes struggle to afford housing. More than 1.3 million children experienced homelessness during the 2018-2019 school year.[23] More than half of all families with children experiencing homelessness on a single night in January 2020 were Black, representing housing challenges that have resulted from ongoing racism and discrimination. In addition, for American Indians, the United States’ failure to honor treaty obligations to provide tribal communities with services and programs, like housing, has resulted in a lack of housing supply and severe physical housing problems in the existing housing stock located in tribal communities.[24]

The policies within BBB offer a comprehensive approach to tackling our nation’s housing crisis. By providing funding for rental assistance for people living on poverty-level incomes, people experiencing homelessness, and survivors of domestic violence, BBB will help more people afford a secure, stable place to live. In areas where the undersupply of housing is a significant issue, investments in construction and rehabilitation of public housing will allow communities to build and preserve more affordable homes for people living on poverty level incomes.

BBB’s expansion of the housing voucher program will reduce racial disparities and improve housing stability. In Montana, 1,500 people will benefit from the expanded access to housing vouchers.[25] Of those 1,500 people, 19 percent are American Indian, 1 percent are Asian/Pacific Islander, 1 percent are Black, 6 percent are Latinx, 3 percent are multiracial, and 69 percent are white, meaning that the program would target racial inequities.

Investments in Indian Country

The United States is what it is today because tribal nations ceded control of millions of acres of land through treaties. In exchange, the federal government guaranteed the continued inherent right of tribal nations to self-govern on their own lands.[26] The United States also declared tribal nations to be domestic dependent nations to whom the federal government has a trust responsibility. This federal trust responsibility stems from treaties and provides federal assistance, such as health care and education, to tribal nations to ensure the success of tribal communities in perpetuity. The federal government has never fully honored its trust responsibility.

Build Back Better will help the federal government meet its trust and treaty obligations to tribal nations through provisions that serve tribal nations and Indigenous people. For example, it would invest more than $700 million in tribal colleges across the country, which are critical to providing American Indians and non-Indians with higher education and workforce preparation.13 BBB also includes funding for child care, infrastructure, and health care for American Indians. For more information on BBB’s investments in Indian Country, see “Build Back Better Would Invest in Tribal and Urban Indian Communities.”

How We Pay for Build Back Better

Congress has set out a plan to pay for these investments. The revenue framework for BBB will raise around $2 trillion over the next decade by asking the wealthiest Americans and large, profitable corporations to pay their share.[27]

Many large, highly profitable corporations pay no federal income tax.[28] Build Back Better would ensure that corporations with profits above $1 billion pay a minimum tax of 15 percent on the profits they report to their shareholders. It also imposes a 1 percent surcharge when a corporation buys back its stock; a scheme often used to shift profits to shareholders without paying dividends.[29] Unfair tax laws related to offshore corporate profits, which have provided an uneven playing field for local businesses, are also addressed.

America’s wealthiest individuals, who are disproportionately white, pay far less than they should in federal taxes.[30] A much-needed high wealth tax will help ensure those with the most begin to pay their share with a surtax on incomes above $10 million. The racial wealth gap results from systemic racism and is directly affected by the impact of taxes on income across race. In the nation, the wealthiest 10 percent of white households hold two-thirds of U.S. wealth, and their wealth is increasing all the time. [31] In 2019, a white family at the median income level had over $188,000 in net worth while a Black family at the median income level had just over $24,000 in net worth.[32] Asking those with extremely high levels of wealth, who are disproportionately white, to pay their fair share in taxes, begins to address the historical unfairness of our tax system and the resulting racial wealth gap.

The policies in BBB will make transformational investments in children, families, workers, and communities. Let’s start 2022 off right, with a commitment to improving racial inequities, meeting trust and treaty obligations to tribal nations, and helping families afford child care, housing, and healthy food.

MBPC is a nonprofit organization focused on providing credible and timely research and analysis on budget, tax, and economic issues that impact low- and moderate-income Montana families.