Montana is currently undertaking a significant criminal justice reform effort, making this an ideal time to incorporate important changes that will benefit American Indians. Criminal justice reinvestment is a comprehensive, data-driven reform approach aimed at safely reducing corrections spending through initial investments and subsequent reinvestments of savings in evidenced-based strategies designed to reduce recidivism and increase public safety. While Montana has made significant efforts to reform its criminal justice system, it should make a more concerted effort to improve outcomes for American Indians.

American Indians are arrested and incarcerated at a disproportionately higher rate than white Montanans; however, there are an array of changes the state can make to combat this. This includes working to ensure that substance use and mental health treatment is more readily accessible both inside and outside of the justice system. Integrating culturally-based, trauma-informed therapies into treatment programs is also crucial, as is making these services available to incarcerated American Indians and those on community supervision. Likewise, providing cultural awareness training to corrections staff is also important for creating supportive environments conducive to positive change for American Indians.

The value of holistic defense and tribally-focused reentry programs cannot be overstated. These programs assist individuals in obtaining driver’s licenses, education/GEDs, legal assistance, transportation, employment, housing, food, cultural mentoring and peer support groups, as well as medical, mental, and behavioral health care, all of which has been proven to significantly reduce recidivism.

By making the changes outlined in this report, Montana can make its criminal justice reinvestment initiative more impactful for American Indians.

Montana Takes Important Steps in Addressing Criminal Justice Reforms

Montana’s criminal justice reinvestment initiative is a three-phase plan (analyze data, adopt policies, measure outcomes) to address the crisis-level increase in criminal justice system activity and associated state spending in a way that ultimately addresses root causes and makes our communities safer.[1]

Despite an overall decline in Montana’s crime rate, the arrest rate increased by 12 percent and the state prison population increased by six percent between FY 2009 and FY 2015.[2] As a result, law enforcement, district courts, and public defenders have experienced a significant increase in workloads, prisons and jails are overcrowded, and the state is spending more than ever on corrections.[3]

To address these serious issues, the 2015 Montana legislature created a fifteen-member Commission on Sentencing to study the situation and propose evidence-based policy solutions.[4] The Commission, comprised of state legislators, judiciary members, corrections officials, county and defense attorneys, local law enforcement executives, and tribal community representatives, requested intensive technical assistance from the Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center, a national nonpartisan, non-profit organization that had successfully conducted the justice reinvestment process in 21 other states.[5]

The Commission found that Montana prisons are currently over capacity with prison populations expected to increase an additional 13 percent by FY 2023, requiring $51 million in new spending for additional supervision staff and contract prison beds and/or building new correctional facilities.[6] Likewise, county jail populations across Montana increased 67 percent between 2011 and 2013, leading to overcrowding in many jails.[7] Additionally, statewide arrests by local law enforcement increased 12 percent between 2009 and 2015 and a majority of these were driven by supervision violations. During this period, bail/bond revocation arrests increased 109 percent, failure to appear arrests increased 189 percent, and parole violations increased 241 percent.[8]

Based on these findings, the Commission developed a series of bills presented to the 2017 Montana legislature.[9] With broad bipartisan support, the 2017 legislature enacted nine of the 12 Commission recommendations. Senate Bills 59, 60, 62, 63, 64, 65, 67, Senate Resolution 3, and House Bill 133 significantly reform the state criminal code and codify the justice reinvestment framework developed by the Commission on Sentencing. Altogether, this legislation aims to “ease capacity issues by focusing prison space and supervision resources on people who are most likely to reoffend and reducing recidivism by improving access to treatment” and “increasing public safety.”[10] (See Appendix A for an overview of each bill.)

To assist with implementation, Senate Bill 59 created a 15-member Criminal Justice Oversight Council to monitor the effects of the criminal justice reform package with the ongoing assistance of the CSG Justice Center. The legislature also made an upfront investment of $3 million dollars to hire additional probation and parole officers in FY 2017 and FY 2018 and to create the local government grant program to enable local governments to create pretrial service programs, establish diversion programs, create supportive housing programs, adopt assurance measures, and to professionalize the parole board.[11]

By enacting these policies, the state is expected to save $69 million between FY 2018 and FY 2023 on contract beds and supervision staff and hundreds of millions more on constructing new correctional facilities.[12]

American Indians in Montana’s Criminal Justice System

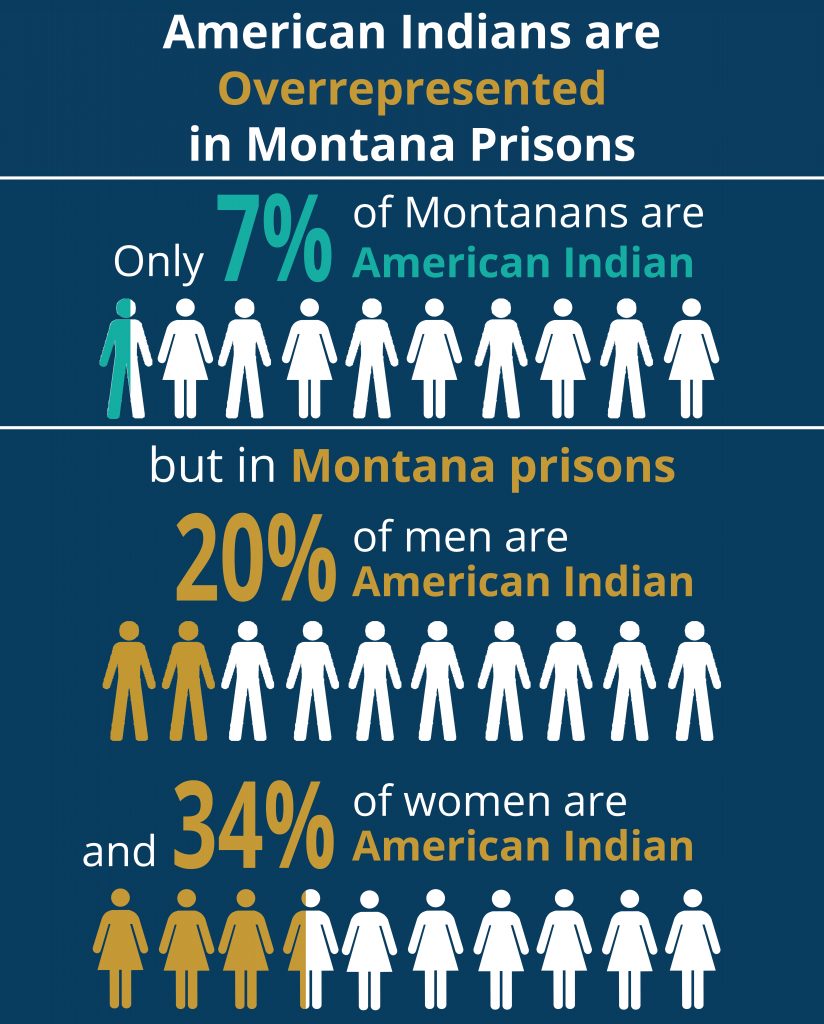

American Indians have long been disproportionately represented in the mainstream criminal justice systems across the nation. It is no different in Montana where, in 2015, American Indians comprised nearly seven percent of the state population but accounted for 19 percent of total Montana Department of Justice arrests, 13 percent of drug arrests, 16 percent of felony arrests, 18 percent of misdemeanor arrests, and 27 percent of arrests for failure to appear and supervision violations.[13]

These numbers for arrests directly translate into a disproportionately high incarceration rate as well. In 2016, American Indians comprised 17 percent of the overall adult state corrections population, where one in five male inmates was an American Indian man and one in three female inmates were American Indian women.[14] Clearly, there is a need for more innovative interventions that can reduce these rates.

Table 1. American Indians (AI) as a Percentage of Various State Populations, June 30, 2017

| % AI Females | % AI Males | |

| Total Montana | 3.28% | 3.32% |

| Total state custody, by gender | 22% | 16% |

| State prison | 33% | 20% |

| Alternative state corrections locations* | 31% | 22% |

| State parole and probation | 20.5% | 14.5% |

| Other jurisdiction custody or supervision** | 9% | 8% |

*Pre-release, chemical dependency/alcohol treatment, assessment/revocation center, county jail

**Interstate compact supervision, federal custody, other state jail or prison

Note: The numbers in Table 1 do not include American Indians incarcerated in tribal or federal corrections facilities. In 2016, the total number of adult American Indians in tribal jails in Montana was 257. Of this, 64 percent were male and 36 percent were female.[15]

Source: Montana State-Tribal Relations Committee, “Facts and Figures: American Indian Offenders in Montana’s Correctional System” (March 15, 2018)

Creating Access to Treatment Should Be Prioritized

Outside the criminal justice system, an estimated one in ten Montanans has a substance use disorder, but only ten percent receive any form of treatment due partly to a documented shortage of treatment providers.[16] Currently, state substance use treatment services are provided in all prisons, the single state-operated inpatient residential treatment center, seven state-contracted private treatment facilities, seven state-contracted pre-release centers, and through 32 state approved community-based substance use treatment providers. Additionally, there are currently two state-approved jail-based treatment programs, one in Butte and one on the Rocky Boy’s Reservation.[17]

Tribal substance use treatment services are provided on each of the seven reservations, typically through contracts with the Indian Health Service. Each reservation-based treatment program includes outpatient treatment and two (Blackfeet and Rocky Boy’s) offer short- and long-term residential treatment. Three of the tribal treatment programs are state-approved. The four urban Indian Health Clinics in Montana (Butte, Great Falls, Helena, and Missoula) also provide outpatient treatment.[18]

Despite these existing options, accessing treatment remains a problem—and this matters because there is a proven link between substance abuse and criminal activity.

In Montana, nearly a third of all rape offenses involve a perpetrator under the influence of drugs or alcohol, and crimes such as theft, burglary, and criminal endangerment are highly correlated with addiction.[19] In fact, drug charges are currently the leading categories for both misdemeanor and felony arrests in the state.[20] Furthermore:

Source: U.S. DHHS, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, “Emerging Issues in Behavioral Health and the Criminal Justice System” (2017)

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has found that a majority of people with substance abuse issues who are involved in the criminal justice system have significant histories of trauma and exposure to personal and community violence—and involvement with the criminal justice system exacerbates this trauma for these individuals.[22] SAMHSA states that “increasing the understanding of traumatic responses enables not only behavioral health providers, but also justice system personnel—from frontline workers to probation and parole officers, judges, lawyers and court administrators—to better respond and develop more effective treatment programs for both adults and juveniles in the justice system.”[23]

SAMHSA also underscores the critical importance of culturally relevant services, asserting that positive change happens when justice system personnel and behavioral and mental health practitioners understand and work within the cultural and linguistic context of the individuals and communities they serve. Thus, they maintain that in order to be most effective, professionals must incorporate community-based values, traditions, and customs into their work—both inside and outside the criminal justice system.[24] For American Indians, this means developing culturally-relevant, trauma-informed therapies and programming.

Culturally-Relevant, Trauma-Informed Services in Practice

The Missoula County Native Outreach Project, a unique grant-funded pilot program with a total budget of $50,000, provided the opportunity for the delivery, as well as the development and implementation of this type of programming in the Missoula County Detention Facility (MCDF). Although American Indians constitute only about four percent of Missoula County residents, they make up 14 percent of the population at MCDF.[25] Project facilitators met weekly with 22 American Indian inmates who volunteered to participate in the four-month long pilot, which took place from October 2017 to January 2018. Inmates were interviewed on a range of topics with the goal of gaging their experiences with and the availability of culturally-relevant services and programming in MCDF, the ways they are un/able to develop or maintain their cultural identity while incarcerated, and whether they believed MCDF had helped prepare them for successful reentry into their communities.[26]

In addition to the interviews, American Indian facilitators offered weekly culturally-relevant, trauma-informed programming, including Mending Broken Hearts and Wellbriety classes, as well as Regaining the Warrior, which were all developed by and for American Indians. Facilitators also provided a cultural awareness training to 80 detention officers. In the end, facilitators compiled a series of inmate recommendations, which offer critical insights into ways the state justice system can better serve its American Indian inmates during and post-incarceration. Among these were the need for:

Many of these echo recommendations from an earlier American Indian inmate focus group held on the Flathead Reservation, where the largest number of American Indian offenders are under community supervision. The focus group was facilitated by the CSG Justice Center in 2016. Here, inmates spoke of the need for corrections staff to be better trained on American Indian culture, reporting that they were prohibited from speaking their tribal (or “foreign”) languages and were required to save up their two-hour faith passes in order to attend a single four-six hour long sweat. Likewise, they reported their desire for more culturally-relevant programming in addition to current Christian-based models like Alcoholics Anonymous. They also noted that many felt overwhelmed by the conditions of their probation and the expense of fines, fees, and treatment costs.[28]

Participants in the CSG Justice Center focus group also identified peer mentoring and support, and assistance with securing housing, employment, and transportation as crucial for successful reentry. This type of support, which both groups identified as needed, is a fundamental component of holistic defense, which has been shown to reduce recidivism by facilitating successful reentry.

Successful Reentry Through Holistic Defense

Holistic defense is an innovative, client-centered model of public defense that achieves better outcomes for clients, their families, and communities. It combines strong legal advocacy with a concerted effort to address the fundamental issues that bring people into the criminal justice system, as well as the collateral consequences of their convictions. The four tenets of holistic defense are: (1) seamless access to services that meet offenders’ legal and social support needs; (2) dynamic, interdisciplinary communication among support team staff; (3) advocates with an interdisciplinary skill set; and (4) a robust understanding of, and connection to, the community served.[29]

Recognizing that a critical component of reducing recidivism lies in the concept behind holistic defense programs, the 2017 Montana legislature passed HB 89 to establish a holistic defense pilot project to reduce recidivism by helping repeat offenders stay out of the criminal justice system by “drawing human support services into the criminal justice system.”[30] (The legislature passed five additional bills outside those in the justice reinvestment package. These bills are closely related, however, in their goal of reducing recidivism related to substance use disorder and include House Bills 95, 278, 333, Senate Bill 228, and House Joint Resolution 6. See Appendix B for an overview of each bill.)

Source: Montana State-Tribal Relations Committee meeting, Presentation by Ann Miller, March 29, 2018.

Holistic defense, which has proven to be highly successful around the country, has also made a significant positive impact in the state of Montana where the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribal Defenders Office has had a holistic defense program since 2011. The program employs case managers who assist clients in obtaining driver’s licenses, education/GEDs, transportation, job training, employment, housing, food, as well as medical, mental, and behavioral health care, and applying for social security and/or other benefits.[31] Reentry attorneys help with parole planning and advocate for tribal members during the presentencing process. The program also partners with tribal behavioral health to ensure seamless access to mental health and chemical dependency services in addition to the clinical psychology services offered in-house at the reentry program office. Finally, the program coordinates an important type of peer support, or cultural mentoring program that assists tribal members in reconnecting to their tribal community by meeting with volunteer mentors approved by the culture committees. Mentoring can take the form of individual counseling with mentors, mediations with persons wronged, or meeting with tribal elders.[32] As a result of these efforts, after the first year, recidivism among these chronic reoffenders went from 100 percent to an astonishing 35.5 percent.[33]

Coordinating Tribal and State Supervision Services

As stated earlier, American Indians accounted for 27 percent of all arrests for failure to appear and supervision violations in 2015.[34] About half of American Indians on state supervision reside off reservations in or near the five major urban areas of the state. The other half reside on reservations or in towns immediately boarding the reservations.[35] The CSG Justice Center found that American Indians on supervision who live on or near reservations “face particular challenges within the criminal justice system, including difficulty accessing state programs and meeting with supervision officers as a result of prohibitive physical distance between the officers and reservations.”[36] Likewise, cellular phone service is oftentimes unavailable or intermittent at best in these rural parts of the state, and many residents do not have landlines.[37] This also contributes to the difficulty people experience in maintaining regular communication with probation and parole officers. Although some probation and parole officers will travel to reservations to meet with people, more is needed—and utilizing tribal supervision services may be part of the solution.[38]

Currently, all reservations offer probation and parole supervision services through their tribal courts. Advisory members of the CSJ Justice Center team suggested that the state should consider entering into cooperative agreements with tribes to utilize these and other reservation-based services to satisfy state probation requirements and monitoring. They also recommended that the state could further prevent supervision violations by accepting reservation-based evaluations, treatment, and urinalysis and invest in re-entry efforts in reservation communities.[39] If the state determines to explore this approach, they should compensate tribes for any of the work tribes do on the state’s behalf, as well as actively investigate new funding streams that might be made available through these types of intergovernmental agreements with tribes.

Conclusion

Despite the fact that American Indians are arrested and incarcerated at a disproportionately higher rate than white Montanans, there are an array of changes the state can make to combat this—and now is the time to make them, as significant changes are already underway as a result of the justice reinvestment efforts.

Making substance use and mental health treatment more readily available inside and outside of the justice system is an important first step. Additionally, focusing on integrating culturally-based, trauma-informed therapies into treatment programs is crucial, as is making these services available to incarcerated American Indians and those on community supervision. Likewise, providing cultural awareness training to corrections staff is important for creating supportive environments conducive to positive change for American Indians. Finally, the value of holistic defense and tribally-focused reentry programs cannot be overstated in assisting individuals with obtaining driver’s licenses, education/GEDs, legal assistance, transportation, employment, housing, food, cultural mentoring and peer support groups, as well as medical, mental, and behavioral health care to reduce recidivism rates.

By making the changes outlined in this report, Montana can make its criminal justice reinvestment initiative more impactful for American Indians.

Policy Recommendations

Appendix A: Overview of Commission on Sentencing Bills, 2017

(Source: Excerpted from Montana Department of Justice, “Substance Use in Montana: A summary of state level initiatives for the Department of Justice,” 2017.)

| Bill Number | Purpose | Effect on offenders with SUD |

| Senate Bill 59 | Requires the Montana Board of Crime Control to develop a prosecution diversion grant program to support the development of local diversion programs.

Codifies the Montana Incentive and Intervention Grid (MIIG) outlining specific incentives and interventions that should be utilized by DOC to respond systematically to a variety of offender behaviors, including drug and alcohol use and treatment program participation. Requires the DOC Quality Assurance Unit to measure program effectiveness and adherence to evidence-based standards. Creates a Criminal Justice Oversight Council to monitor the effects of the criminal justice reform package with the assistance of CSG. |

Local jurisdictions which receive funding may develop programs that divert offenders with SUD to treatment.

DOC-supervised offenders with SUD who relapse or do not comply with treatment will be provided with a series of stepwise interventions that offer access to treatment and monitoring as a first-line response instead of revocation. DOC may increase its monitoring of contracted treatment programs to ensure use of evidence-based standards. Data will be collected and analyzed on the effects of these bills.

|

| Senate Bill 60 | Creates a 30-day limit for pre-sentence investigation (PSI) reports and funds a pre-sentence investigation unit within the Division of Probation and Parole to dedicate resources to generate PSIs.

Funds a pre-sentence investigation unit within the Division of Probation and Parole to dedicate resources to generate PSIs. Requires DOC to validate its risk and needs assessment tool. |

Individuals will receive a timely PSI using a validated risk and need assessment score to identify offenders who are well suited for drug court, treatment and/or other diversion programs. |

| Senate Bill 62 | Creates certification for behavioral health peer support specialists by the Board of Behavioral Health. | Treatment, recovery and justice system programs like Drug Courts can use paid peer support specialists working under a licensed clinician, into their services and behavioral health workforce. |

| Senate Bill 63 | Requires that DOC use the MIIG and exhaust and document violation responses before revoking a deferred or suspended sentence.

Limits imprisonment for probation compliance violations to nine months once the appropriate violation responses under DOC’s incentives and interventions grid have been exhausted. Defines a compliance violation, ensuring that the violation of the conditions of supervision is not a new criminal offense. Allows DOC hearings officers to impose up to 30-day sanctions, or recommend up to 90 days of electronic monitoring, day reporting, or placement in a community corrections facility for probation compliance violations without resorting to a petition to the court. Requires probation and parole officers to recommend conditional discharge for probationers who are compliant with supervision conditions after specific amounts of time. |

Offenders with SUD violations will be provided treatment, monitoring and other progressive, step-wise interventions before their sentences are revoked or suspended.

Offenders with SUD who relapse will be less likely to be charged with a new criminal offense. Offenders with SUD who successfully complete treatment and remain drug and alcohol free may be rewarded with reduced periods of probation and parole.

|

| Senate Bill 64 | Establishes a full-time, five-member parole board to increase opportunities for training and skill development that will enable the board to make more informed and efficient parole decisions

Requires the Board of Pardons and Parole to use a structured grid for decision making to increase consistency, transparency and predictability for victims. Allows DOC hearings officers to impose up to 30-day sanctions, or recommend up to 90 days of electronic monitoring, day reporting, or placement in a community corrections facility for parole compliance violations without resorting to a petition to the parole board. Limits imprisonment for parole compliance violations to nine months once the violation responses under DOC’s incentives and interventions grid have been exhausted. |

Offenders with SUD being considered for parole will be treated with consistency. |

| Senate Bill 65 | Creates a supportive housing grant program in the Montana Board of Crime Control.

Allows DOC to provide housing vouchers for up to three months for those in need being released from prison |

Offenders with SUD being released from prison will be more likely to have supportive housing, which should aid in their continued recovery and connection to needed services. |

| Senate Joint Resolution 3 | Designates an interim committee to explore how Montana could increase access to tribal resources for tribal members who are involved in the state’s criminal justice system. | Because tribal members are more likely to be incarcerated, this committee will help the Legislature to better understand issues that effect this population, including SUDs. |

| House Bill 133 | Provides a lesser penalty for sharing drugs versus selling drugs.

Removes jail time for first time possession of minor amounts of marijuana. Mandatory minimum sentence for possession of marijuana with the intent to distribute removed and cap reduced from 20 years to five years. Mandatory minimum for a conviction of criminal production or manufacture of dangerous drugs removed. Allows judges to sentence offenders to evidence-based treatment and treatment-based supervision. Allows inmates to be released to chemical dependency programs, not just pre-release programs. Allows judges the option of sentencing felony DUI offenders to placement in a drug treatment court program. |

Individuals who are sharing, not selling, drugs will not be prosecuted as dealers.

Fewer low-level drug offenders will sit in Montana’s overcrowded jails. Mandatory minimum sentences, which take away judicial discretion and have been shown to contribute to prison and jail overcrowding, are now eliminated for some drug offenses. More individuals charged with substance use-related crimes may be sentenced to treatment and treatment-based supervision. Some felony DUI offenders may receive community-based treatment and monitoring in drug treatment court instead of placement at the DOC residential treatment WATCH program. |

Appendix B: Overview of Other Substance Use Related Bills, 2017

(Source: Excerpted from Montana Department of Justice, “Substance Use in Montana: A summary of state level initiatives for the Department of Justice,” 2017.)

| Bill Number | Purpose | Effect on offenders with SUD |

| House Bill 278 | Amends MCA 46-18-201 to allow judges deferring a sentence to send offenders directly to chemical treatment so long as they have the approval of the program and confirmation by the DOC that space is available. | Offenders with an SUD may now be sent directly to DOC chemical treatment programs instead of first being committed to the DOC for assessment. |

| House Bill 89 | Establishes a “holistic defense” pilot project in four locations within the Montana Office of the Public Defender which will address chemical dependency and mental health issues for indigent clients. | Low income clients with substance use issues will be able to access support for treatment while they receive legal defense through the Office of the Public Defender in four pilot locations. |

| House Bill 95 | Removes geographic limitations on the number of state-approved substance use treatment providers in Montana. | Access to treatment may increase as providers will no longer be prohibited from opening a treatment facility or practice in an area where there is already a state-approved provider. |

| Senate Bill 228 | Exempts non-profits and public health departments which provide needle exchange services from drug paraphernalia laws. | Increases access to harm reduction programs for injection drug users. |

| House Joint Resolution 6 | Creates an interim study on the effects of methamphetamine and opioid use on state and local services. | The Legislature will be more informed on the impacts of substance use in Montana. |

MBPC is a nonprofit organization focused on providing credible and timely research and analysis on budget, tax, and economic issues that impact low- and moderate-income Montana families.