Having a safe, stable place to call home can determine our success in life. Montana must invest in the critical resources that all families need, like good homes that people can afford. Families without access to a safe and affordable place to live are at higher risk of becoming involved with the child protection system. Furthermore, housing problems can be a barrier for family reunification when living conditions are considered a threat to child safety.

Keeping families safely together is possible if caregivers can provide the essentials. Addressing housing needs is one strategy to prevent children from being placed in foster care or achieve timely reunification. Montana should take these steps to stabilize families and, ultimately, reduce the number of children living in foster care.

A Home Is the Foundation for Healthy Children and Families

The importance of stable housing for children is well-documented. Children living in owned or affordably rented homes fare better in health, in academics, and in their adult lives than children who are precariously housed. For many families on low incomes, finding an affordable, safe, right-sized home is a challenge.

| Those earning the state minimum wage would need to work 75 hours a week to afford two-bedroom home. |

The Department of Housing and Urban Development defines affordable housing as costing no more than 30 percent of a household’s monthly income. As of 2017, 45 percent of Montana children in families on low incomes lived in housing where expenses, including rent, mortgage payments, and utilities, surpassed this threshold.[1] The gap between wages and the cost of housing places working families under immense strain. In Montana, the Fair Market Rent for a two-bedroom apartment is $830 a month. A parent working full time must earn $15.97 an hour to afford this level of rent and utilities. Those earning the state minimum wage would need to work 75 hours a week to spend no more than 30 percent of their monthly income on a two-bedroom home.[2] The current shortage of affordable and available rental homes for households living in poverty means that only 45 such homes exist for every 100 households at this income level.[3]

While the majority of families living in poverty do not come to the attention of child protective services, poverty and economic disadvantages make families more vulnerable to a child protection intervention due to charges of neglect.[4] In some cases, a family becomes involved with child protective services because their substandard housing conditions (e.g. overly crowded household, environmental hazards, homelessness) can risk the health and safety of their children. In other cases, housing plays an indirect role. A parent’s struggles to pay the rent can have negative impacts on a child’s health and cognitive development, likely because their families are left with fewer resources to meet other essential needs. Toxic stress caused by living in poverty can compromise parenting capabilities and a parent’s ability to meet their children’s basic needs, leading to neglect.[5] Being insecurely housed can also worsen other problems, including behavioral health and substance use disorders.

Inadequate housing is pervasive in child neglect cases and a major factor contributing to the placement of children in foster care. For 10 percent of children currently in the nation’s foster care system, inadequate housing was reported as a reason associated with removal.[6] Families involved in a child and family services case often experience hardships including struggling to afford food, housing, and utilities.[7] Nearly half (47 percent) of families who have a child removed from the home report having trouble paying for basic necessities.[8]

Safe reunification of families can be delayed or prevented altogether by a family’s inability to secure affordable and safe housing. Children spend more time in foster care despite their parents being ready to care for them, even if housing problems were not what brought them to the attention of child protective services in the first place. One estimate finds that 30 percent of families fail to reunify because parents lack safe housing and child protection agencies cannot provide access to the housing needed to return a child home from foster care.[9] A reason for this is that many states prohibit removing children due solely to inadequate housing or homelessness but are less likely to return a child if their family is seen as unable to provide a stable place to live.

Yet, child protection workers are provided few options to provide the housing and material supports families need to achieve well-being and permanence. Research investigating the intersection between housing and child wellbeing has noted that, “for many years, the child welfare system has been bearing the burden of America’s affordable housing crisis most often using the only tool afforded it by current federal financing constraints, foster care placement.”[10]

| Timeline for Reunification

When a child is removed from their family and placed in foster care, working towards reunification is the goal in nearly every case. The federal Adoption and Safe Family Act, however, sets a timeline for reunification efforts. When a child has lived in foster care for 15 of the most recent 22 months, reunification efforts cease, and states are required to initiate proceedings to terminate parental rights. The strict time frame is intended to protect the best interests of the child by limiting their time spent in foster care and securing a permanent living situation as soon as possible. This requires parents, child welfare professionals, and family courts to resolve cases in a timely way or risk permanent removal of a child from their family. |

The Link Between Foster Care and Housing

Much of what is known about the relationship between inadequate housing and child well-being involvement comes from national studies. Unfortunately, there are many gaps in knowledge as to how this relationship impacts families and foster care rates in Montana. Montana’s Department of Child and Family Services completes detailed assessments but does not consistently track related factors like housing needs and homelessness of families in its care. Thus, the prevalence of severe housing problems among families in the state is not only difficult to quantify but likely underrepresented. Likewise, the extent to which a family’s housing circumstance indirectly contributes to foster care placement, directly delays, or prevents reunification efforts is unknown.

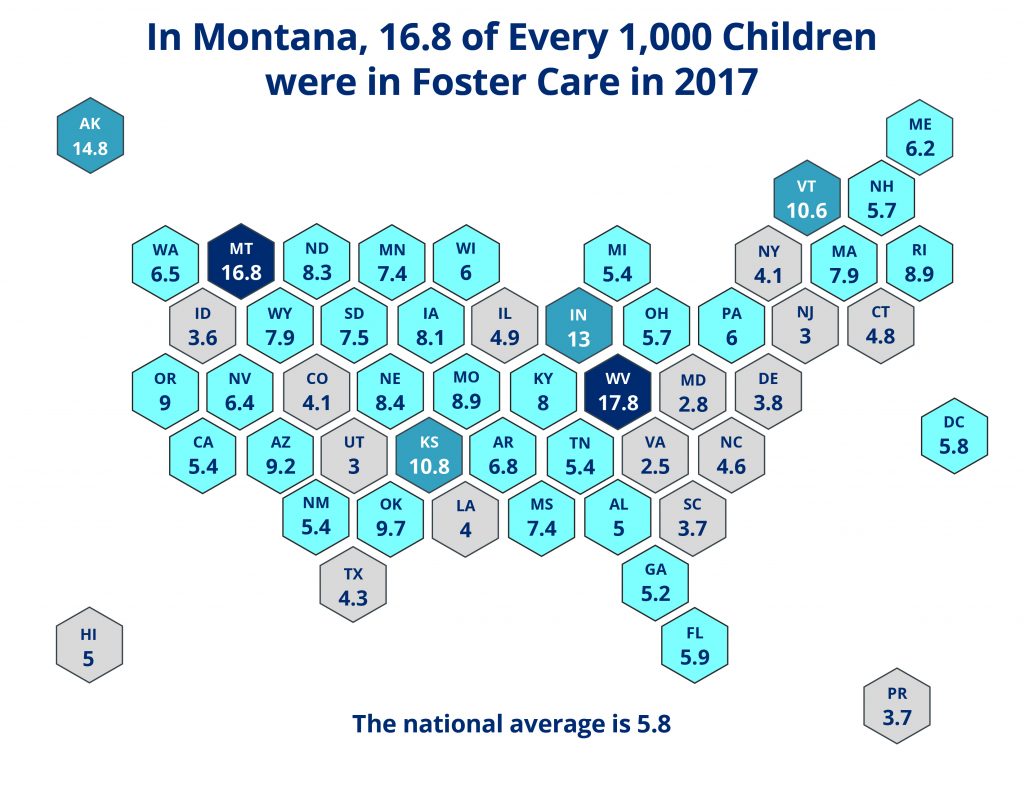

The number of Montana children in foster care has more than doubled in the last 10 years.[11] Montana has the second highest rate of child removal to foster care in the nation. In 2017, 16.8 of every 1,000 children were in state foster care, compared to the national average of 5.8, according to analysis by Child Trends.[12] Neglect is by far the most common allegation prompting an investigation by Child and Family Services (CFS), the division of DPHHS that provides state and federally mandated protective services to children who are abused, neglected, or abandoned; these cases comprise 93 percent of all child abuse and neglect cases in Montana.[13] Neglect is the primary reason children enter foster care, and inadequate housing is one of the main causes of neglect.[14] Half of these substantiated cases result in foster care placement for the children involved.[15]

Much policy and media attention focus on parental drug use as the primary driver of foster care placements in Montana. Indeed, substance abuse poses a severe and urgent problem: of the 3,934 children in the state foster care system in 2018, 65 percent of those cases attributed parental drug use or involvement as a circumstance for their removal.[16] While parental substance use disorders may be why families come to the attention of CFS, many also face multiple, interconnected challenges that are extremely difficult to overcome — such as social isolation, poverty, housing and food insecurity, and domestic violence.[17]

Montana defines child neglect as a failure to provide needed food, clothing, shelter, and medical care to the degree that the child’s health and safety is harmed; yet, the circumstances under which a failure to provide is attributed to neglect versus poverty are not well-defined.[18] Interviews conducted by the author with social workers, family law attorneys, court-appointed special advocate volunteers (CASA), volunteers, and officials with CFS affirm that inadequate housing is not the primary reason for a child protection investigation or foster care placement.[19] However, all agree that a real problem facing Montana is that many parents struggle to regain custody of their children because they cannot find a safe and affordable place to live. Family court judges and social workers cannot guarantee the safe reunification of a child with their family if that family is not stably housed, even if housing is not what brought families to the attention of protective services to begin with.

The consensus opinion among the child protection professionals interviewed is that not being able to secure adequate housing presents the real possibility that parents can permanently lose their parental rights after the timeline for reunification expires. The shortage of available housing for households on low incomes means that parents are often unable to find a home in their community, even if they qualify and receive financial assistance to help pay the rent. The removal of a child can lead to other compounding challenges that make reunification even harder to achieve. For example, eligibility for certain assistance programs, like the Special Supplement Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) is tied to the child. Other programs, like the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP) and Housing Choice vouchers, provide benefits based on the number of people in the household. A change in family composition can result in losing assistance. Without these supports, a parent can lose the housing and financial benefits they need to provide the basics for their children. In most separation cases, parents are ordered to participate in counseling, treatment programs, and find regular work. If a parent cannot manage to spend the many hours necessary to complete multiple programs, meet work requirements, and do not have the financial means to meet their own basic needs, they can be judged to not adequately care for their children and fail to reunify.

Housing Solutions Are Key to Success

Children deserve to grow up in stable home. Their parents provide for a child’s basic needs and offer a safe and secure bond that children need in order to develop healthy attachments. Secure attachments come from the child’s perception of their primary caregiver’s availability and physical access. When children experience separation, their sense of safety and security is disrupted, and they cannot understand the reasons for the absence.[20]

It is widely demonstrated that foster care placement creates emotional distress and leads to long-lasting trauma for children.[21] The longer they remain in foster care, the worse the outlook becomes for their health and well-being. Furthermore, the longer children remain in foster care, the longer they are likely to wait for a permanent family. Many children living in foster care do not need to be there. Their families can successfully and safely care for them when they have the necessary supports.[22] When possible, children are better protected from trauma by living at home while their parents receive the services they need to stabilize the family.

Supportive Housing Keeps Families Together

It is extremely difficult for parents to overcome the problems that contributed to a child protection investigation unless they and their children have a safe and stable home. A subset of families need more intensive support to stay intact. Supportive housing is a type of therapeutic program that combines structured, subsidized housing with on-site services for residents. Case managers work with families living in the home to coordinate delivery of services and supports for parents. This intervention model allows parents to concentrate on their health and stability, rather than worrying about where they will spend the night, while living together with their children. There is promising evidence from supportive housing pilot programs across the country that combining housing with services results in positive childhood outcomes and offers an effective alternative to foster care.[23]

One example of a supportive housing program that is funded and administered by state-level child protective agencies and public housing authorities is the Supportive Housing for Families Program in Connecticut. This program is a partnership between Connecticut State Department of Children and Families, the state housing authority, and The Connections, Inc., a state-wide nonprofit. This program provides residential-based service interventions for families at risk of, or who have already had a child placed in, foster care. Families are referred to the program through the Connecticut Department of Children and Families. Evaluation of the Supportive Housing for Families Program showed that over 90 percent of families in this program maintained permanent housing and that 88 percent of families remained intact. Research also showed that using state dollars to subsidize housing saved the state between $14-$21 million a year by avoiding foster care placements.[24]

Serving American Indian Families

There is no single approach that is appropriate for all families, and interventions must recognize the family connections and culture in which parents raise their children. In responding to the needs of American Indian children and families, it is essential that supportive services are available, culturally-responsive, and accessible. Interventions must account for intergenerational trauma endured by American Indian communities and today’s overrepresentation of their children in foster care. From 1880 to the mid-1960s, federal government policy ripped generations of American Indian children from their home and culture, placing them in government-run boarding schools and homes that forced assimilation into white culture. The effect of child removal and the destruction of traditional family and community systems threatened cultural genocide for American Indians. This legacy is a cause of intergenerational trauma felt by tribal communities today and persistent inequity in child removal practices today.

Congress passed the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) of 1978 to address both the abusive removal practices targeting American Indian children and respect their political status and cultural values. ICWA’s intent is to protect the best interests of American Indian children and to promote the stability and security of American Indian tribes and families. It sets federal regulations that apply to state child custody cases involving children who are members, or eligible for membership in a federally recognized tribe. ICWA requires a higher burden of proof to remove children from their home and, in cases where a child is placed in foster care, applies a preference for placing them with extended family or other members of their tribe.[25] The child’s tribe has the right to intervene or request that state child protection proceedings be transferred to tribal jurisdiction. Although the law has been in place for 40 years, noncompliance with ICWA is still widespread. State child protection systems routinely do not identify tribal membership or notify tribes of child protection proceedings and adopt children away even if relatives are available.[26]

In Montana, foster care placement remains highly disproportionate for American Indian children who currently make up 34 percent of the foster care population.[27] This does not include children living in tribally-run foster care. To correct this disparity and improve implementation of ICWA, Yellowstone County established the Indian Child Welfare Act court to handle all family court cases involving Northern Cheyenne, Assiniboine, Crow, and Sioux children. Montana is the fifth in the nation to offer a specialty court dedicated to ICWA.[28] Tribal governments, family members, and the state court system work together to offer a better informed and culturally sensitive approach for families during child protective proceedings and keep decision-making within the tribe. Families have better access to resources like summer camps and education enrichment, and services like substance use recovery and behavioral health treatment that promote healing through connection to culture.

In the first year of the court, there were fewer re-removals in Yellowstone County's ICWA cases (12 percent) than in non-ICWA cases (16 percent). American Indian parents last year were less likely to lose their children a second time when they worked through the specialized ICWA process.[29] This approach to keeping American Indian families together shows early promise. Expanding ICWA specialty courts and its resources available for families can be a strategy to repair the disparities in foster care system.

Housing Is a Smart Investment in Children and Saves Resources

One of the best proxies for estimating the cost of inadequate housing to the child protection services system is spending on foster care versus services to prevent removal in the first place. On average, foster care placement costs the federal government $56,892 a year, according to the Department of Housing and Urban Development. By comparison, rental assistance combined with supportive services for families costs $14,000 per family.[30]

Investing in proactive and preventative measures on the front end is the most effective strategy to improve childhood outcomes. It is also the most cost-effective. Public expenditures for in-home interventions and material supports like housing assistance can be offset by reduced spending in other systems like foster care. In a recent survey of child protection agencies, 60 percent of states and 62 percent of counties surveyed reported cost savings as a result of caseload reductions.[31] Of responding states and counties, 44 percent and 40 percent respectively reported that they reinvested these savings in prevention and permanency services. Finally, when respondents reinvested in prevention, 75 percent of states and 59 percent of counties reported fewer children entering and reentering the foster care system.

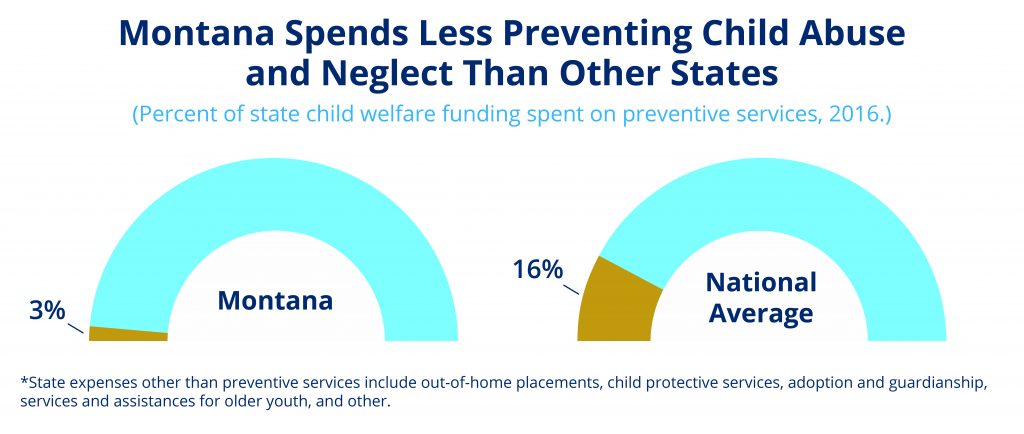

State protective agencies and nonprofit childhood service providers use several major funding sources to administer their programs and deliver services, each with their own specific purpose and usage limitations. In Montana, funding for child protective services provided by CFS comes from a combination of federal and state dollars. In fiscal year 2016, Montana’s total child welfare expenditures was $81 million, but Montana uses its federal and state funds differently than the national pattern.[32] Montana spends 41 percent of federal funds and 37 percent of state funds on foster care placements. Montana spends 2 percent of federal funds and 3 percent of state funding on prevention services, as compared to the 13 percent and 16 percent spent on average by other states.

The largest federal source of funding is Title IV-E funding that until recently only covered the cost of foster care, adoption, and guardianship, but not the cost of family preservation and reunification services. The Families First Prevention Act passed by Congress in 2018 changes how foster care is funded by giving states and tribes the ability to use Title IV-E funding to prevent children from entering foster care.[33] Staring in 2019, states are able to direct Title IV-E funds for prevention services like treatment for temporary substance abuse, supportive housing, and home visiting programs to help keep families together. Since the introduction of Families First in 2018, 25 states have introduced bills dealing with aspects of the legislation, including expanding in-home parenting programs and supportive housing for families recovering from substance use or mental health disorders. Montana will not be ready to access Title IV-E funding for prevention until 2021. As Montana develops its implementation plan, the state must consider the role housing insecurity plays in destabilizing families and delaying family reunification. Using Family First to invest in front-end services and housing resources will help keep families safely together and reduce the number of children living in foster care. Furthermore, one estimate shows that Montana could save over $2 millions a year in foster care spending if it instead uses federal funds to subsidize housing and provide services to reunify families.[34]

A Plan for Moving Forward

Identify families for housing need. A lack of statewide data makes it difficult to measure how common inadequate housing is among families and how housing affects family reunification. Child and Family Services should include “inadequate housing” as a data element in its assessment tools. This data element must specify the nature of the housing problem, including cost burden, substandard housing, living in overly crowded housing, or homelessness. With this data in hand, caseworkers can identify the subset of families for which housing is a barrier, identify obstacles to finding housing, and incorporate housing stability plans as part of the services offered.

Build partnerships between child protection advocates and housing providers. Meeting the housing needs of families requires cross-system collaboration. Child protection agencies should formalize relationships with affordable housing providers (such as public housing authorities and local nonprofit housing providers) through which families can be referred for subsidized housing, rent assistance programs, and encourage public housing agencies to provide a local preference for families involved with the state agencies seeking public housing or housing choice vouchers.

Invest in prevention and supportive housing programs. Successful prevention strategies require helping the entire family, focusing both on the child’s safety and well-being and the parents’ emotional and economic well-being. Investing in housing supports and meeting other material needs is less costly than foster care and improves family functioning in the long term. The Montana Legislature should invest in resources and programs aimed at preventing child neglect before it occurs. Montana should also provide families assistance directly by using its federal Title IV-E waiver funds for housing supports.

Ensure child protection professionals inform state budget decisions. Child protection professionals should be actively involved in forming state budget decisions and policies that impact at-risk families. Where Montana allocates its dollars reflects the state’s values and priorities. If we are to protect children, improve long-term child outcomes, reduce rates of foster care placement, and keep families safely together, we must build up the resources, technology, and maintain manageable caseloads that allow professionals to effectively serve families.

MBPC is a nonprofit organization focused on providing credible and timely research and analysis on budget, tax, and economic issues that impact low- and moderate-income Montana families.