On November 3, 2015, the state of Montana began enrolling individuals in newly expanded Medicaid, called the HELP (Health and Economic Livelihood Partnership) Plan. In conjunction with the open enrollment period for health insurance on the Marketplace, Montana successfully enrolled thousands into Montana’s Medicaid expansion plan. However, Medicaid enrollment is open year-round, and the state should consider additional steps to reach newly eligible Montanans and continue the successful efforts to enroll individuals in affordable health care coverage.

As of March 1, 2016,36,320 Montanans have enrolled for affordable health care coverage.

Early Enrollment Levels Shows the Need for Affordable Health Care Insurance

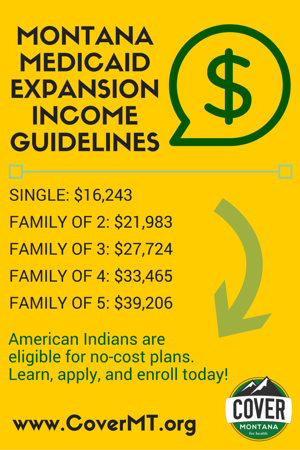

On November 2, 2015, the state of Montana received approval from the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to expand health care coverage under the bipartisan HELP Act. Already, over 36,000 Montanans have enrolled.[1] This plan expands Medicaid coverage to individuals making less than 138 percent of the federal poverty level (an income of $16,200 for an individual and $27,700 for a family of three).[2] Montana contracted with a third-party administrator (Blue Cross Blue Shield) to provide new enrollees’ benefits using its existing network of doctors and providers, process claims, and make payments on behalf of the state. CMS approved the HELP Act’s requirement that those enrolled in the HELP Plan will pay modest premiums.

The plan also exempts certain individuals from the HELP Plan who will be enrolled in the state Medicaid plan and exempt from premiums (though may be subject to copays).[3] These exempt populations include: American Indians, those with exceptional health needs, and eligible individuals with family incomes below 50 percent of the federal poverty line (ex., individual with annual income less than $5,990, or $490/month). Pursuant to federal law, American Indians are exempt from all cost sharing.

The majority of those who enrolled in the first two months were those at very low incomes. To date, over 22,000 (or 61 percent) of the newly enrolled are living with incomes below 50 percent of the federal poverty line (FPL), or those with annual income less than $5,800 for a single individual.[4] The state has enrolled a far greater portion of uninsured individuals below 50 percent due, in part, to extensive pre-enrollment work in November and December.[5] The state and enrollment advocates should focus upcoming outreach efforts on populations between 50 and 138 percent of FPL. Most of this population will be subject to premiums, so it will be important to include detailed information on premiums and why it is important to have health insurance.

The state and enrollment assisters have also successfully enrolled over 4,300 previously uninsured American Indians.[6] However, while American Indians represent nearly 20 percent of the eligible uninsured population, to date, American Indians encompass only 12 percent of the newly enrolled.[7] Thousands more American Indians are eligible for coverage but have not signed up, emphasizing the importance of outreach to Indian Country and urban Indians.

Recently released county data also shows differences in enrollment levels among larger population counties. For example, when comparing enrollment in the five largest counties in the state (Cascade, Flathead, Gallatin, Lewis & Clark, Missoula, and Yellowstone counties), Gallatin County is lagging behind enrollment levels compared to the other four largest counties.[8] Consistent with statewide numbers, enrollment of American Indians in these counties is below the overall proportion of American Indians eligible.[9]

In addition to efforts by the Montana Department of Health and Human Services, community health centers and other entities in the state have joined forces to help increase awareness and enrollment outreach. Cover Montana (www.covermt.org) provides detailed information on who is eligible for Medicaid expansion coverage, as well as coverage in the open Marketplace. The website includes detailed information on why having health insurance is important, a calculator for individuals to determine eligibility, and how to find enrollment assistance in their communities.

Lessons Learned from Other States on Effective Outreach Strategies

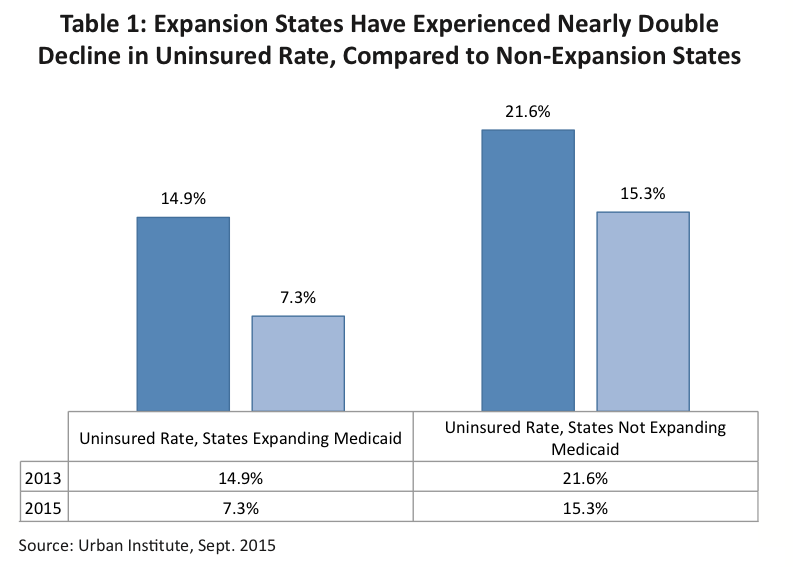

Montana has become the 31st state to expand Medicaid, and we now have the opportunity to learn from other states on continuing outreach and enrollment efforts beyond the open enrollment period for the Marketplace. The expansion of Medicaid has had a significant impact on reducing the number of uninsured adults in the country, with states expanding Medicaid experiencing nearly double the decline compared to those states that have not expanded (see Table 1).[10]

Many states that expanded Medicaid have seen higher enrollment levels than originally anticipated.[11] For example, the Commonwealth of Kentucky experienced nearly double the enrollment in the first year than previously expected, with over 310,000 individuals enrolling.[12] A comprehensive study in 2014 on the impact of Kentucky enrollment shows greater economic benefits, including dramatic decline in the uninsured rate and lower uncompensated care costs.[13]

Increased coverage for adults has also resulted in greater enrollment levels for children, as parents discover their children are eligible for the state’s children’s health insurance program (CHIP). For example, the state of Washington experienced record enrollment for CHIP during the first year of Medicaid expansion.[14] Most states that expanded Medicaid witnessed high enrollment levels during the first open enrollment process. Since then, enrollment continues to grow but at a slower pace.[15]

While many states are in their third year of Medicaid expansion enrollment, we can learn from some of the initial challenges and how better to coordinate enrollment here in Montana. The remainder of this report provides “lessons learned” and some examples of effective strategies in other states.

Outreach Materials

Outreach materials should include information on why it is important to obtain and maintain health insurance coverage. For example, in a national survey of low-income adults about the Medicaid program, individuals cited several reasons that motivated them to enroll, including the ability to access care when a health emergency occurs, protection against expensive medical bills, and the ability to access preventative care and regular check-ups.[16] Outreach advocates can emphasize that those with health care coverage experience more efficient use of health care services, have lower medical debt, and report better overall health.[17]

Many states have utilized a variety of messages to encourage enrollment in Medicaid. The states that have been most effective incorporated Medicaid expansion enrollment into their Marketplace open enrollment outreach materials, but states have also acknowledged that Medicaid enrollment outreach must continue beyond the open enrollment period. States have seen successes where they have allowed navigators and others engaged in enrollment to tailor the enrollment materials to local conditions.[18] For example, the state of Washington provided local navigators flexibility in modifying enrollment materials for different regions of the state.

The state should continuously collect and analyze outreach and enrollment data to better target future efforts. The Colorado Health Institute conducted a detailed analysis of uninsured levels based on zip code. It found that uninsured levels dropped across the state from 2013 to 2015, particularly in the Denver area, but more work remained in neighborhoods with high concentration of low-income families, renters, and Spanish-speaking communities dispersed throughout the state.[19] Colorado also targeted rural areas through direct mail cards with details on who qualifies and how to apply.[20] Outreach coordinators sent these cards to rural mailing routes in the highest uninsured zip codes and explained that consumers may qualify for low cost health insurance. The cards also included supporting organizations’ contact information and the nearest place to find assistance.

Lessons Learned: Outreach Materials

1. Include why it’s important to have health insurance - it motivates people to enroll.

2. Ensure that Medicaid-eligible individuals understand that enrollment is year round and continues after the Marketplace enrollment period ends.

3. Tailor outreach materials to fit local communities and continuously analyze where best to target outreach.

4. Highlight and promote personal stories of those who have accessed coverage.

Some states have also highlighted individual stories about accessing affordable coverage to show the positive impact of enrollment.[21] For example, Colorado’s marketplace and Medicaid enrollment website includes specific testimonials from individuals who have benefited from coverage.[22] The state of Washington has included on its Facebook page short video testimonials on how accessing coverage has impacted individual enrollees.

Utilizing Community Health Centers and Trusted Community Partners

Community health centers continue to be a critical partner in outreach and enrollment. Nationally, 60 percent of health center patients are adults under age 64, many of whom fall in the Medicaid coverage gap.[23] In those states that have expanded Medicaid, community health centers have seen the percentage of those seeking services that are uninsured fall by 29 percent, as newly eligible adults enroll in Medicaid coverage.[24] Community health centers are often trusted messengers to uninsured patients. The state should consider detailed outreach and enrollment trainings for all providers, including mental health, pediatric, dental, and vision providers.

In Colorado, community health centers used creative ways to engage current uninsured patients, including: (1) writing “prescriptions” for coverage or creating a referral in the electronic health record to an enrollment assister; (2) attaching fact sheets on importance of coverage on patient prescription sheets; and (3) playing educational videos in waiting rooms so patients can learn more while they are waiting for health services.[25]

States have also successfully utilized community locations, such as shopping malls, libraries, and schools, to educate the public about affordable health coverage and enroll individuals in Medicaid. For example, Kentucky outreach coordinators utilized local festivals to conduct “kynect”-branded giveaways and answer questions about enrollment.[26] The state of Washington set up kiosks at local malls and tied its marketing campaign to the idea of “shopping” for affordable health insurance.[27]

The state should also consider additional outreach at locations serving families experiencing poverty, including food banks, soup kitchens, public transit, and income tax assistance programs. Colorado enrollment assisters engaged for-profit entities, including pizza delivery companies and supermarkets, to include enrollment information during delivery or checkout.[28] Kentucky has utilized community leaders, including faith leaders, to help spread the word of health insurance opportunities.[29]

States have also established actual enrollment sites in communities with high eligible populations. Kentucky created a permanent storefront that housed enrollment assisters and its health agency staff.[30] In the second open enrollment period, Colorado established temporary enrollment sites, including in rural areas. Other states emphasized that it was important for assisters to go into the community rather than stay in one office location.[31] This could be particularly important in rural and tribal areas.

Lessons Learned: Utilizing Trusted Community Partners

1. Utilize local physicians and community health centers to stress the importance of accessing health coverage.

2. Providing detailed trainings to health providers, including vision and dental facilities, to help encourage enrollment.

3. Community organizations, including tribal entities, churches, low-income advocates, and food banks, can be key partners in reaching certain populations.

4. Partnering with private businesses, including food delivery services, grocery stores, and utility companies.

States have utilized trusted community groups to engage minority populations, including American Indians. Colorado Community Health Network worked with IHS to request referrals, particularly for clients living in rural areas without immediate access to an IHS facility.[32]

Health Literacy: Explaining How Insurance Works

Because Montana’s HELP Plan includes provisions that are outside of the traditional Medicaid plan, it is important for the state to provide additional information on things like premiums, copays, and the risk of disenrollment. This will ensure newly eligible individuals understand what requirements they may have to meet and provide as much detail as possible on whether a new enrollee will be subject to premiums and copays, and if so, how much. Imposing premiums on individuals enrolling in the new plan could have a detrimental impact on enrollment, so it is important for those engaged in outreach to educate newly eligible adults on the exemptions and the benefits of having health care.[33]

In many instances, newly eligible individuals will be exempt from the HELP Plan and enrolled in the state Medicaid plan. These individuals will include American Indians, those with exceptional health needs, and individuals with family incomes below 50 percent of the federal poverty line. It is important that these individuals understand they are exempt from premiums (and, for American Indians, also exempt from copays).

Other states have included specific health services that an enrollee can access in their materials to explain the benefits of having health care, even with the cost of modest premiums. For example, Indiana launched a public information campaign to educate new enrollees, including the potential costs of not having insurance, such as out-of-pocket costs to deal with emergency health issues.[34] Indiana has also provided detailed “Frequently Asked Questions” section on its website to help newly enrollees understand the required contributions and copays, the risks of disenrollment, and when and how an individual can reenroll.[35] Indiana’s Medicaid enrollment website also provides an online chat platform, so individuals can ask questions and receive real time responses. Montana could also consider developing short videos, similar to those created by the Consumer Reports Health, to provide easy to understand explanations of premiums and copays for newly enrolled individuals.[36]

Health Care Coverage for American Indians

With Montana’s expansion of Medicaid, tens of thousands of American Indians in the state will now have access to health insurance, but it is critical for outreach efforts to take into consideration the unique dynamics of American Indians accessing health care through Indian Health Service (IHS).

During the 18th century, the federal government made agreements with American Indian and Alaska Native tribes in exchange for land and natural resource ownership. As part of these agreements, the federal government assumed responsibility for the provision of heath care to American Indians.[37] Consistent with these federal obligations, newly eligible American Indians will be enrolled in traditional Medicaid and are not subject to premiums or copays.[38]

Depending on location, American Indians can access health care services at IHS, tribal, and Urban Indian health clinics, often abbreviated as I/T/U health programs. In Montana, there are three tribal hospitals, ten health centers for outpatient care, and five urban Indian health programs located in Billings, Great Falls, Helena, Missoula, and Butte.[39] While American Indians receive health services through I/T/U facilities, the federal government has not met its treaty and legal agreements to provide adequate funding.[40] The federal government has funded IHS at approximately 60 percent of the actual need.[41]

If an American Indian has health care insurance – whether it is Medicaid, Medicare, or private insurance – the I/T/U has the ability to bill the insurance provider for health services. This third-party billing allows I/T/Us to preserve its limited federal resources. For American Indians enrolled in Medicaid, the federal government pays 100 percent of the billed cost (with no fiscal impact on the state).[42]

Indian Health Service (IHS): Federal agency responsible for providing health services to American Indian and Alaska Natives.

I/T/U: Health care providers operated by IHS facilities, tribes, or urban health clinics.

Purchased/Referred (PRC) Care: Funds provided to cover the cost of services not available at IHS clinics or tribal health care facilities and purchased from private health care providers.

Bill: Process by which health care providers submit claims to health insurance companies in order to receive reimbursement for services provided.

Third-party billing: An intermediary processes claims, invoices, and payments between health care providers and health insurance companies.

If an individual (without insurance) is unable to receive services at an IHS or tribal health facility due to limited capacity, unavailable equipment, or professional expertise, and needs to receive services from a private health care provider, IHS and tribal clinics can receive a limited allocation of funds to refer this patient for care. This care is known as Purchased/Referred (PRC) Care - formerly known as contract services.[43] Congress provides very limited PRC Care funds, and in order to prioritize the most critical medical conditions, IHS uses a strict medical priority system in which requirements often constitute a “life-or-limb” litmus test.

Further, urban Indian health clinics are not eligible for PRC Care funds, and American Indians living away from their contract health service delivery area may no longer qualify for PRC Care through their home reservations, IHS facilities, or tribal clinics.[44]

This lack of funding has left many American Indians without access to services they need to stay healthy. As a result, IHS covers only a limited range of basic and triage services in specific communities. In fact, even when American Indians have access to health care, they often report experiences of dealing with stereotypes, disrespectful and dismissive treatment, lack of understanding and respect for one’s traditions and practices, substandard care, and even turned away from care.[45] And while American Indians face significant health disparities, partly as a result of historic inequities and structural racism, “they often must seek treatment from a health care system similarly characterized by racial inequity.”[46] It is critical that outreach efforts to enroll American Indians in Medicaid recognize the challenges that Americans Indians face in accessing health services.

Because of the dynamics surrounding health care coverage in Indian Country, outreach efforts need to emphasize how having health insurance relates to accessing care through I/T/Us, both for the recipients’ own care and for the ability of IHS facilities to increase their capacity and improve their health care services generally. Outreach efforts should continue to inform current and newly enrolled American Indians about their ability to access care at IHS, tribal, and urban Indian clinics. Outreach should emphasize that enrollment allows clinics to access reimbursements for services through Medicaid, which frees up IHS funds to increase and improve health services for their communities. Additionally, when American Indians have access to Medicaid, they can seek services outside of IHS and tribal health clinics, which relieves pressure on IHS’s limited PRC Care funds.

Lessons Learned: Outreach in Indian Country

1. Utilize staff and expertise at IHS clinics and urban Indian clinics to refer customers who may be uninsured to apply online or visit a health navigator.

2. Ensure community enrollment activities are coordinated with I/T/Us.

3. Outreach materials must incorporate information about continuing to access care at I/T/Us as well as the additional benefits of having health insurance coverage.

The state of Montana and health navigators should continue to partner with IHS and tribal clinics, including coordinated outreach events. For example, the Blackfeet Community Hospital in Browning has coordinated outreach efforts with Benefis Health in Great Falls, and community health centers in Shelby and Cutbank. By including I/T/Us at the table from the beginning, outreach efforts can more successfully tailor information for American Indians and target uninsured individuals already accessing services.

Conclusion

Montana has experienced successful initial enrollment levels in its Medicaid Expansion plan, validating the need for access to affordable health care coverage for tens of thousands of Montanans. As the state moves forward outside of the Open Enrollment period on the Marketplace, it should continue to utilize existing community partners to expand outreach and enrollment. Other states have successfully deployed outreach strategies that should be considered in Montana. Furthermore, the state can and should increase its efforts to target specific populations, including American Indians, to emphasize the importance of health care coverage.

Acknowledgement

The work upon which this report is based was funded, in part, through support from the Montana Healthcare Foundation. The statements and conclusions of this report are those of the Montana Budget and Policy Center.

MBPC is a nonprofit organization focused on providing credible and timely research and analysis on budget, tax, and economic issues that impact low- and moderate-income Montana families.