The novel coronavirus pandemic lays bare deep inequities across Montana. Due to a long history of racist public policies, ongoing settler colonialism, and underinvestment, Montanans who are American Indian disproportionately experience underlying health conditions and economic challenges that heighten the risk of the pandemic. That same history continues today by denying tribal nations the resources needed to respond to and recover from emergencies of this scale.

Given the impact of the pandemic and the federal government’s chronic underfunding of Indian Country, the $10 billion in tribal funding provisions included in the federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act is not enough. Tribal nations are underfunded and overextended but continue to take steps that prioritize the health and well-being of communities. For example, at the time of the writing of this report, the Blackfeet Nation maintains its COVID-19 ordinance that includes the closure of entrances to Glacier National Park located within the reservation.[1] On May 13, the Crow Tribe of Indians extended its emergency orders to June 15 and helped coordinate COVID-19 testing available to all residents of Big Horn County.[2],[3] However, they could do more with additional resources. Now, the state must act on its opportunities to effect change in Indian Country.

Montana has a tremendous opportunity to create the change the state has always needed. Without action, the coronavirus could take a serious toll on Indian Country and Montana. This report outlines why the state must target its response in Indian Country and offers the following recommendations:

The novel coronavirus and COVID-19, the disease the virus causes, present serious public health concerns for Indian Country. This is no coincidence. Because of racist public policies and ongoing settler colonialism, indigenous peoples across the United States experience disproportionate underlying health conditions and economic challenges, circumstances that heighten the risk and severity of the virus.[4] While the number of confirmed cases on reservations in Montana is low at the time of this report, an outbreak could be severe.

Research shows that, by April 10, 2020, the rate of COVID-19 cases per 100,000 was more than four times higher for people living on reservations than it was for the United States as a whole.[5] As of May 14, available data shows that the five highest case rates in the country are in tribal nations, with the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians having the highest rate (4,741 cases per 100,000 people). For comparison, the Navajo Nation ranks fifth (2,764 cases per 100,000), and the state of New York ranks sixth (1,858 cases per 100,000).[6]

While documented cases do not show that the novel coronavirus has disproportionately infected Montanans who are American Indian, the data does tell us that Montanans who are American Indian suffer more severe complications as a result of COVID-19 than do white Montanans. As of May 1, 2020, nearly one-third of American Indians with COVID-19 have needed hospitalization, versus 13 percent of white Montanans.[7]

This is consistent with national data. Nationally, 34 percent of American Indian adults age 18 through 64 are at a higher risk of serious illness if infected with the coronavirus. This is greater than all other racial and ethnic groups. Among the total adult population age 18 through 64, 21 percent are high-risk.[8]

Underlying health conditions are part of the problem. Montanans who are American Indian are more likely than white Montanans to experience health conditions, such as diabetes and respiratory diseases. These are complications that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has determined to put people at high risk for severe illness from COVID-19.[9],[10] Montanans who are American Indian already live a generation shorter than white Montanans. The median age at death is 63 for American Indian women and 82 for white women, while it is 60 for American Indian men and 75 for white men.[11]

The novel coronavirus pandemic highlights inequities that present us with opportunities to emerge as a state where all Montanans can thrive. The following sections discuss just some of the factors that could worsen the spread and impact of the coronavirus in Indian Country. To be clear, many of the issues Indian Country faces today are the result of discriminatory policies that non-tribal governments enacted that continue to deny tribal communities access to resources and opportunity.

Housing

Access to safe housing is critical to practice social distancing, one measure to help prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus. However, overcrowded housing, or having more than one person per room, disproportionately impacts Indian Country. Estimates for overcrowded households in tribal areas range from roughly 16 percent to nearly 33 percent, as compared to 2.2 percent of all U.S. households.[12],[13] Given the higher rates of underlying health conditions and the way in which the virus spreads, overcrowded housing in Indian Country is of particular concern.

Water Infrastructure

Handwashing is crucial to staying healthy during the coronavirus pandemic. However, American Indian households are more likely to lack access to adequate plumbing. This is in part due to the federal government’s failure to adequately fund tribal housing and infrastructure programs. According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 5.6 percent of American Indian households and 1.3 percent of all U.S. households have plumbing problems, such as lacking piped hot water.[14] This creates barriers to taking simple measures, such as handwashing, to stay healthy.

Access to Health Care

Access to quality health care is key to respond to a coronavirus infection. The Indian health system needs resources to ensure that Montanans who are American Indian can access that care. Treaties between tribal nations and the federal government provide the legal obligation for the federal government to provide health care for American Indians.[15] However, the federal government chronically underfunds the Indian Health Service (IHS), as current funding levels meet just 60 percent of IHS needs.[16] In 2016, IHS health-care expenditures per person amounted to $2,834, while federal health-care spending nationwide was $9,990.[17] This means American Indians are less likely to get the care they need.

Funding shortfalls do not only impact reservation communities. Less than 1 percent of IHS funding accounts for urban Indian health programs.[18] Yet, nearly 7 out of every 10 American Indians and Alaska Natives live in urban settings.[19] Roughly 40 percent of Montanans who are American Indian live off reservations.[20] This matters because urban Indians tend to experience even lower health outcomes than American Indians living on reservations and are more likely to seek health care from urban Indian health programs than from non-Indian clinics.[21],[22] To serve their patients, urban Indian health programs must find funding outside IHS.[23]

Because Montanans who are American Indian are disproportionately uninsured, accessing health care outside of the Indian health system can be challenging. Some 25 percent of nonelderly Montanans who are American Indian are uninsured, as compared to 9 percent of nonelderly white Montanans.[24]

While reservation communities in Montana have seen low case counts so far, they are not insulated from the consequences of the pandemic. Tribal governments and reservation economies face unique challenges that do not position them well to respond to and recover from the coronavirus pandemic.

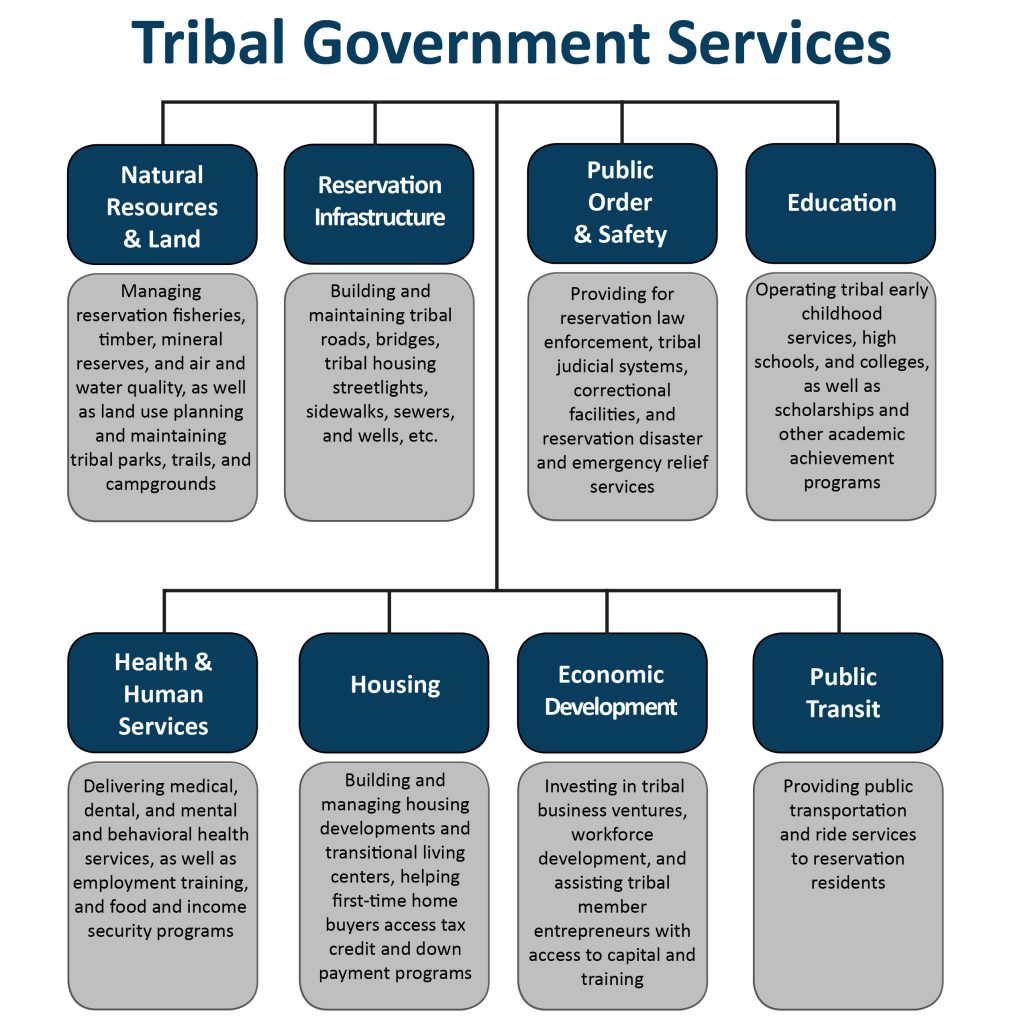

As with any other government, tribal governments need revenue to perform government functions and provide essential services, such as public health, education, public safety, and more (see the graphic for a list of tribal government services). However, non-tribal taxing jurisdictions deny tribal governments the ability to fully operate government programs, services, and functions. Over time, state and local governments have successfully challenged in court tribal governments’ exclusive right to levy taxes within their reservation boundaries to the point that tribal taxation authority is greatly diminished today. As a result, tribal governments must provide many of the same services as other levels of government without the usual tax revenue on which other governments rely.[25]

Instead, many tribal nations must rely on natural resources, leases, and tribally owned enterprises as their only source of revenue outside of federal dollars.[26] As exampled above with IHS funding, federal funding of Indian Country is inadequate. Despite this, states have fought for the ability to co-tax certain economic activities involving non-Indians in Indian Country, extracting wealth from tribal communities and creating a system that can hamstring reservation economic growth.[27]

This limited revenue foundation has serious consequences for tribal nations. As of April 10, 2020, more than half of tribal governments expected large drops in revenue from tribal enterprises, which often fund tribal government activities. Nearly 40 percent of tribal governments projected those decreases would continue for at least six months.[28] That means tribal governments are less able to support government operations that benefit Montanans. Tribal governments anticipate growing financial need as time passes, with 25 percent indicating they need more than $1 million now and 42 percent indicating they will need more than $1 million in six months.[29] Now is the time for non-tribal taxing jurisdictions to allow tribal governments to generate the revenue needed to provide services that benefit all Montanans.

The consequences of the novel coronavirus will reach beyond Indian Country. According to the Department of Commerce, tribal nations in Montana contribute roughly $1 billion annually to the state economy in public-sector dollars alone.[30] That number is based on data from years 2003 through 2009 and is not adjusted for inflation. Therefore, it is likely that $1 billion is a low figure. Strained tribal revenues could mean a lower economic stimulus and reduced government operations that keep Montanans healthy and safe. State inaction now hamstrings the strength of tribal nations.

Not only do tribal governments provide economic contributions and services that benefit Montanans, tribal governments play an important role in the ecosystem of employment in the state. They are often one of the largest employers in their regions and provide employment opportunities to both American Indians and non-Indians. As of April 10, 2020, nearly half (47 percent) of tribal governments across the country had already cut staff, and 50 percent anticipated needing to make cuts in six months. Only 16 percent of tribal governments expected no negative changes in staffing in six months.[31]

The consequences of the pandemic are not limited to tribal public sectors. The novel coronavirus has already hit the private sector in Indian Country. According to one April 2020 survey of private-sector tribal businesses in a four-state region that includes Montana, 38 percent of businesses had already closed, 89 percent projected they would close by June 8, and 100 percent expected to close by October. Of those still in operation, businesses had laid off 26 percent of their employees, cut hours for 83 percent of employees, and placed 86 percent of employees on leave without pay[32]

This has real consequences for real people. At the time of the survey mentioned above, lost wages for employees had already amounted to as much as $1.4 million and could grow to as much as $8.3 million in six months.[33] That means greater economic challenges for individuals and families, less economic activity in local and regional economies, and less tax revenue for governments to provide services that keep Montanans safe and healthy.

Tribal governments are taking steps to keep Montanans healthy and safe. Now, the state must act on its opportunities to better position all communities to respond to and recover from emergencies.

MBPC is a nonprofit organization focused on providing credible and timely research and analysis on budget, tax, and economic issues that impact low- and moderate-income Montana families.