Nearly half of American renters are cost burdened and households of all incomes struggle with rising housing costs and limited affordable housing options. The need for more affordable homes is most severe for low-income renters, yet only one out of four households eligible for federal rental assistance receives it due to limited funding.[1] With 2015 federal spending for housing assistance $2.9 billion (6 percent) below 2004 levels, there are fewer resources to meet the nation’s spiking affordable housing needs.[2] The Department of Housing and Urban Development’s “Worst Case Housing Needs 2017 Report” reported that between 2001-2016 the number of very low-income households (those making less than 50 percent of the area median income) receiving rental assistance grew by 600,000; however, during that same period the number of very low-income households grew by 4.3 million.[3] In addition, households struggling with “worst case needs,” defined as spending more than half of income on rent and/or living in severely substandard housing conditions, spiked from 34 to 43 percent.

The affordability crisis has put more pressure on states and local jurisdictions to close the funding gap and produce the housing their residents need. In response, state and municipal governments are finding innovative ways to leverage local resources and build capacity to provide housing for residents, apart from federal funds.

Despite the growing need for affordable housing, Montana does not spend any state money on housing assistance. Housing assistance programs in Montana are supported through federal dollars and private donations.[4] Montana currently offers one state-supported affordable rental housing program called the “Elderly Homeowner or Renter Credit,” that offers a tax credit up to $1,000 for lower income seniors who rent or own their homes.[5] In 1999, Montana’s legislature created the “Montana housing revolving loan fund” to provide direct assistance for low- and moderate- income residents struggling to meet basic housing needs.[6] However, this fund has not received any funding since it was established.

State, county, and city governments play a major role in setting the regulations that impact housing and are well positioned to bring together stakeholders from the private sector, nonprofits, and community as partners in comprehensive housing policy. In order to expand its affordable housing supply and assist our lowest income households, Montana policymakers can look to how other states and cities across the country, and right here in Montana, are implementing policies that address housing needs and draw on best practices to design programs that meet our own needs and priorities.

This report discusses innovative strategies used by states and local jurisdictions across the country and in Montana to promote affordable housing and provides case studies to highlight best practices.

Montana Summary

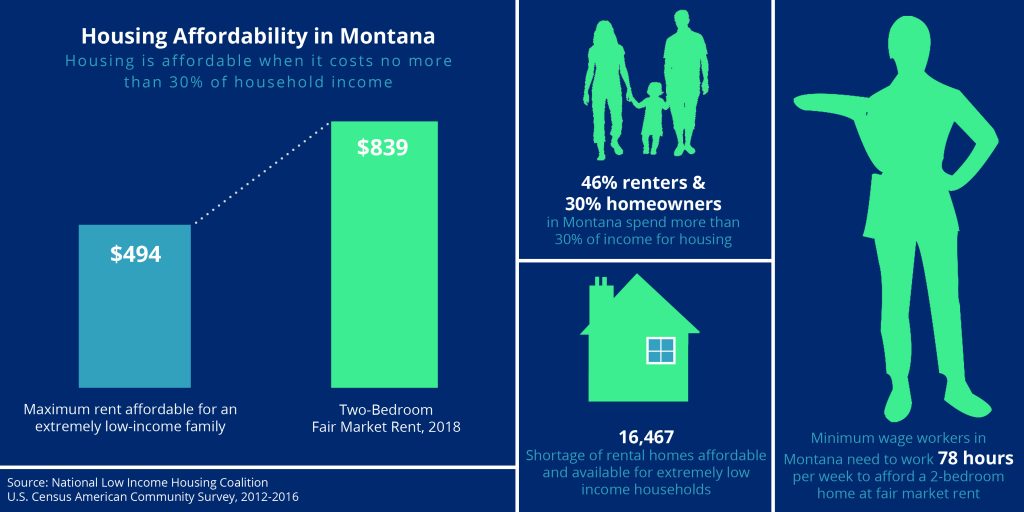

In Montana, 46 percent of all renters are cost burdened - paying more than 30 percent of their household income towards housing costs.[7] One in four renters are considered extremely low-income, and the majority (68 percent) of these households pay rents that are unaffordable.[8]

Although Montana’s average housing costs are lower relative to the rest of the county, they have skyrocketed in recent years, ranking Montana’s rent costs the 11th fastest growing in the nation.[9] Wages in Montana remain very low, the 45th lowest nationwide, and workers in minimum and low wage occupations now make up more than a third of extremely low-income, cost burdened renter households. Exacerbating the housing crisis is the fact that there are only 52 affordable homes for every 100 extremely low-income renters.[10] As a result, minimum and low wage earners are left with few housing options that do not consume an excessive portion of their income; in fact, low-income Montanans now spend ten percentage points more of their income on housing compared to what they spent two decades ago.[11]

For the lowest income households, the lack of affordable housing options forces many renters to either spend a higher portion of their incomes on shelter, to settle for poor quality housing, or, in the most extreme cases, to be unable to secure any housing, leading to homelessness.

Local strategies to build and preserve affordable housing

With federal funding levels at its lowest in a decade, more states, counties, and cities are using their own resources to fund affordable housing projects, ranging from rental assistance to capital support for housing development. In addition to creating local funding streams through public revenues and private- public partnerships, states are looking at policies that leverage existing federal programs and funding. For example, there are 242 active state programs and 71 city programs across the country that fund low-income housing rental programs, separate and apart from any federal dollars they receive.[12]

The following section describes three strategies that state and local jurisdictions can use to create and preserve affordable housing and provide housing assistance to low-income community members.

Housing Trust Funds

Housing trust funds are distinct funds that collect public revenues to provide a stable source of funding reserved for affordable housing. Housing trust funds help guarantee that revenues are available each year for states and localities to support their critical housing needs. Because these trust funds are designed at the state, county, and local level, policymakers have considerable control over securing a dedicated revenue source that is tailored to local conditions. They also have flexibility in determining how to use these funds and in establishing eligibility requirements and program activities based on particular local needs and priorities.

According to the Center for Community Change, more than 770 housing trust funds in cities, counties, and states generate more than $1 billion a year to support critical housing needs, making this model a well-established part of affordable housing policy.[13] Real estate transfer taxes are the most commonly used revenue source for state housing trust funds.[14] Other revenue sources commonly used include interest from state-held funds (such as unclaimed document recording fees).

On average, a state housing trust fund leverages about $7 dollars from other public (including federal dollars) and private sources for every $1 dollar of state public revenues the fund commits to an activity.[15] A city level trust fund leverages about $6 for every dollar spent.

Trust funds that focus on renter and homeownership stipulate that funded activities must be affordable to low- and extremely low-income households. In addition, there are often long-term affordability requirements attached to housing developments supported by trust funds. As the model evolves and housing needs grow, states are becoming more creative in how they expand the reach of these funds and in making them more sustainable, including: passing legislation allowing local jurisdictions to create housing trust funds; sharing a new public revenue source with local funds; and providing matching funds to support local funds.

In 2013, Nashville-Davidson County created the first metro area affordable housing trust. The Barnes Fund for Affordable Housing was initially funded by a combination of federal dollars, grants, and donations, and now has $10 million in county general funds committed annually. The trust also receives funding by collecting one cent from the tax Nashville assess on short term rentals such as Airbnb or VRBO. The trust funds the renovation and construction of affordable rental and homeowner properties and donated city owned property to nonprofit developers on which to build affordable housing, an arrangement known as a Community Land Trust.

Since the program began, the Barnes Housing Trust Fund has invested over $27 million of county dollars, leveraged over $127 million from other sources, and developed over 1,300 affordable housing units.

Source: National Association of Counties

Lessons Learned

A housing trust fund is most productive when the funding sources are sustainable, generate predictable levels of revenue, and are tailored to local conditions. Finding and securing a stable revenue source is often the largest barrier to creating a housing trust fund. Some states impose more control over municipal activities, restricting local governments' ability to develop affordable housing policies and generate financial resources. State law and regulations can prohibit a particular type of revenue source, or from establishing a dedicated funding stream.

As previously noted, the most common revenue sources for housing trust funds are real estate transfer taxes and fees. However, a 2010 Montana constitutional amendment specifically prohibits taxing real estate transfers, thus, this revenue source cannot be used to fund a housing trust fund in the state. Despite this, Montana can look to revenue sources related to tourism (e.g. the resort tax) or lodging facilities taxes as a potential funding stream for communities that are experiencing a booming housing market, or for smaller communities whose economy is driven by tourism. For example, Montana state law allows incorporated towns with populations below 5,500, or below 2,500 for unincorporated towns, and whose economy is based on tourism to apply a resort tax up to three percent on hotels, restaurants, and luxury goods. Big Sky is one of 10 designated “resort areas” in the state that levies a sales tax on tourism-related goods and services and, in 2018, used $1.9 million of its resort tax revenues to finance the Big Sky Community Housing Trust.[16]

State Low-Income Housing Tax Credits

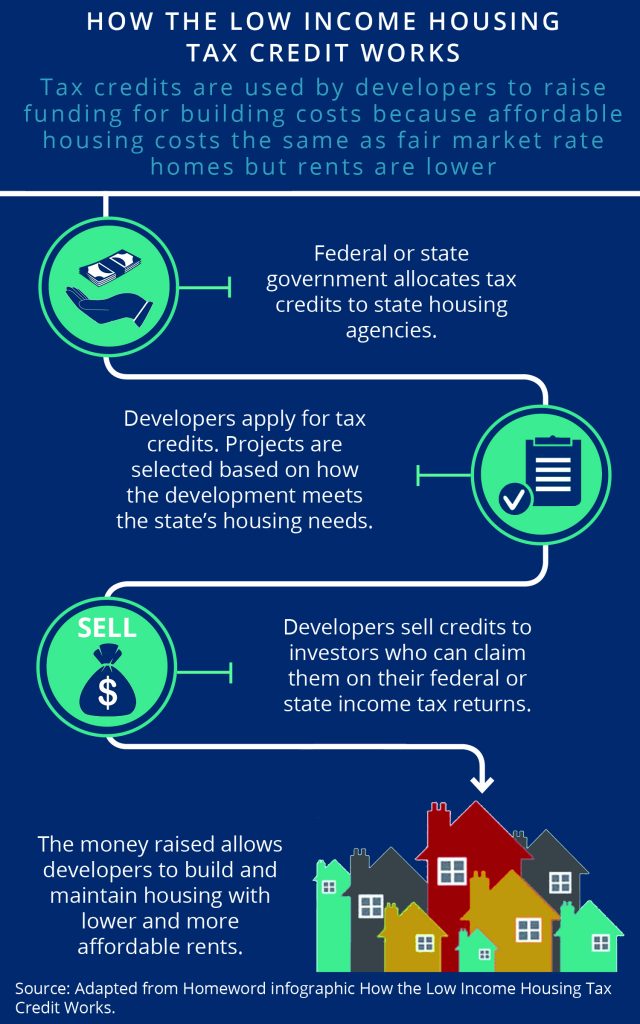

Montana’s Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) is modeled on the federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program. The federal LIHTC is the largest source of new affordable rental housing in the nation and has financed the construction and preservation of more than 2.8 million affordable apartments since the program was created in 1986.[17] The LIHTC program provides income tax credits to developers of affordable (costing no more than 30 percent of income) rental housing to tenants with incomes 60 percent or less of the area median income.

Low-income housing tax credits make it financially feasible to complete the construction of an affordable housing project and to offer rent priced below the area’s fair market rent for qualified residents.

The LIHTC program provides 9 percent tax credits, which are allocated to state housing finance agencies annually based on population, and 4 percent tax credits, which are available to qualifying rental housing developments funded with tax-exempt bonds.

The 9 percent tax credit subsidizes 70 percent of an affordable housing development’s cost and the 4 percent tax credit subsidizes 30 percent of development costs. States receive a limited number of 9 percent credits each year and award these credits to developers through a competitive selection process, whereas the number of 4 percent credits are unlimited and there is no competitive process to use them.

Housing developers apply in a competitive process for these tax credits and those who are awarded sell the credits to an investor. The investor can claim the tax credit and receive a reduction in their taxes. Under the federal LIHTC program, an investor receives a dollar-for-dollar reduction on their federal taxes for ten years. Under a state LIHTC program, an investor receives a reduction on their state taxes, but the number of years an investor can claim the credit varies by state program. Developers use the proceeds from selling tax credits to fund the affordable housing development project.

The Colorado LIHTC provides state tax credits to support acquisition, rehabilitation, and new construction and expand the state’s supply of affordable housing. The Colorado Housing and Finance Agency (CHFA) is budgeted $5 million annually in state tax credits and is granted a total of $150 million in tax credits until the program sunsets in 2024. The recipient of the state tax credit can claim the credit for six years, unlike the federal LIHTC that allows ten years.

Colorado’s LIHTC program primarily focuses on financing the development of housing. While residents living in housing supported by the program must be at a certain low-income level to qualify for housing, the communities and specific populations served vary by development. Housing directly supported by the state LIHTC serves families, veterans, formerly homeless households, and seniors. Certain developments provide simply housing, while others partner with local nonprofits to integrate supportive services for residents.

By 2017, the sale of combined state and federal LIHTCs directly supported 1,299 affordable rental units and leveraged $11.3 million in federal credits, nearly doubling the number of 4 percent deals completed annually since the program began. The addition of the state LIHTC program also enabled Colorado to attract higher levels of private sector investment, with over $168.3 million in equity raised for affordable housing projects. The economic impact of this program is evident- although it has been in place for only three years, the development of the 1,229 affordable rental units generated over $525 in economic impact and supported 3,289 jobs.

Source: SB 18-007 Affordable Housing Tax Credit bill and Colorado State LIHTC 2017 allocation report.

Lessons Learned

As demand for rental housing grows, the amount of housing tax credits available to states have not kept pace. Developers requested more than $2.4 billion in 9 percent tax credits in 2013, over three times the number of credits available.[18] However, the federal 4 percent credit is among the most underutilized sources of federal funding because the equity generated by 4 percent credits is often too low to cover the cost of development, compared with the 9 percent credit. State housing tax credits are designed to leverage the federal 4 percent credit by pairing an additional subsidy to housing projects supported by the 4 percent tax credit. The additional financing offered by the state tax credits provides developers the gap resources needed to make federal 4 percent credit deals financially feasible and helps ensure that federal dollars for housing do not go unused.

The state housing tax credit program provides an opportunity for states to reserve their limited allocation of 9 percent tax credits for lower density housing projects that are more expensive to build and require deeper levels of subsidies. Housing developers working in sparsely populated and remote areas typical of rural America are unable to tap into the economies of scale available in more densely populated areas, making materials, labor, and transportation costs more expensive and overall construction often not financially viable. State tax credits help alleviate overall demand for the federal 9 percent credits and free up deeper subsidies for the most expensive housing projects.

Tax Increment Financing

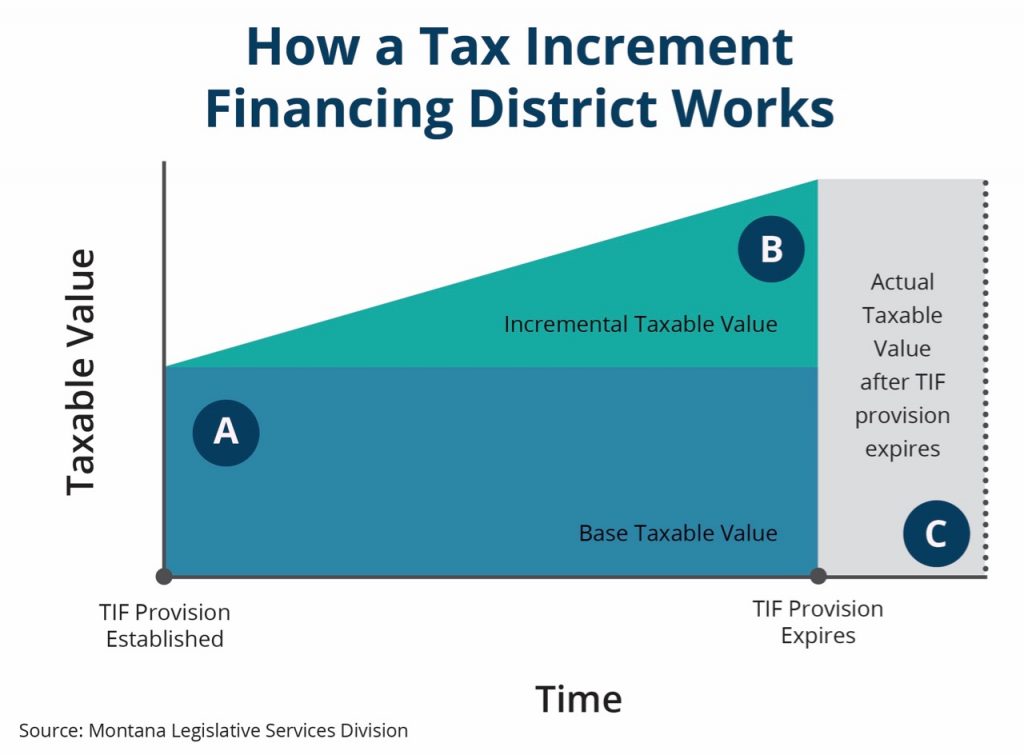

Tax increment financing (TIF) is a funding tool that allows cities and counties to generate money for a group of blighted properties or a neighborhood targeted for improvement, known as a TIF district. As improvements are made within the TIF district, the increases in its property tax revenue are used to pay for economic and community development projects within the district.[19] Targeted districts must meet certain criteria for blight and infrastructure deficiencies that have discouraged or prohibited new investment. Development projects can range from utility upgrades, parks and trails development, cleaning contaminated sites, and housing development.

When a TIF district is created, the district measures the current value of all its taxable property, known as the base taxable value. Over the life of the TIF, typically 15 years, property taxes remain frozen at the base rate for existing taxpayers located in the district, and the amount of property tax revenue received by schools and other public services in the district is frozen at their base rate amount.[20] Meanwhile, new investments and improved public amenities increase the value of property in the area. Taxes collected on the growth in property values above the base amount is redirected as tax increment revenue to pay for improvements within the TIF area. At the end of the TIF provision, the entire value of the property is returned to the city or county, and the municipality will benefit from a much higher property tax base than it would have without the investments.

TIF is widely used to revitalize distressed areas and is a demonstrated way to create jobs, expand the tax base, and increase an area’s property values.[21] As of 2016, there were 55 active TIF districts in 24 local governments.[22] To date, TIF districts in Montana added more than $10.5 million in taxable value to the state’s tax base and this amount is expected to reach $22.2 million in 2018.[23]

The SweetGrass Commons in Missoula’s Old Sawmill District provides 27 apartments for low- to moderate-income residents. The building was developed by Homeword, a nonprofit affordable housing developer, and financed by public and private sources, including tax increment financing through the Missoula Redevelopment Agency (MRA). In order to develop SweetGrass Commons into permanently affordable housing, the MRA purchased land owned by Homeword using TIF dollars and then sold the property back to Homeword at half the purchase price. The MRA is the first in the state to use their TIF revenue for affordable housing construction. Extending TIF assistance to Homeword helped both the city and developer finance the construction of the SweetGrass Commons and attach permanent affordability requirements to the property.

Source: “Homeword Looks to Sawmill District for Affordable Housing.” Helena Independent Record. July 19, 2015 and Andrea Davis. Personal communication. June 29, 2018.

Lessons Learned

Traditionally, TIF is a way to finance economic development and municipalities are expanding its use to support affordable housing projects. Because TIF programs increase property tax revenues by way of increasing the value of real-estate, TIF funding can have the effect of gentrifying a neighborhood and making the area unaffordable to existing residents and businesses. Affordable, high quality housing is an essential piece of any community improvement strategy and it is important that TIF-supported development is inclusive.

Furthermore, stakeholders such as small business owners, renters, and elderly or low-income homeowners may feel at-risk by proposals for large scale TIF-funded development, as they may not be prepared for the higher tax burden generated by the intended higher property values. To ensure that TIF does not cause displacement of existing residents, local governments can adopt provisions for using these funds including establishing protections such as property tax deferral programs for groups at risk for displacement or requiring a certain percentage of TIF revenue to be set-aside specifically dedicated to developing affordable housing for low- and moderate-income individuals. For example, the city of Atlanta, Georgia requires that 15 percent of its Beltline TIF dollars be dedicated to affordable housing development and the city of Dallas, Texas requires that 20 percent of all housing receiving TIF funding be affordable to low-income households.[24]

Conclusion

In response to the growing affordability crisis and the diminished federal role in funding housing programs, states and local governments have increasingly had to develop alternatives to federal housing assistance to meet the housing needs of low-income individuals and families. The three programs described in this report can provide a useful tool for communities in Montana seeking to increase their affordable housing options, yet these policy and funding tools are only pieces of a comprehensive housing strategy. Addressing housing affordability requires sustained commitment of state and local public resources and bringing together community stakeholders who best know the needs and capacity in their communities.

MBPC is a nonprofit organization focused on providing credible and timely research and analysis on budget, tax, and economic issues that impact low- and moderate-income Montana families.