Introduction to Individual Income Taxes in Montana

For generations, our tax dollars have served as shared investments in the programs and services that make our state a great place to live, work, and play. Tax dollars enable Montanans to work together for those things which we could not achieve alone, like educating our children, building infrastructure, keeping our air and water clean, and paving the way to a strong economy for everyone.

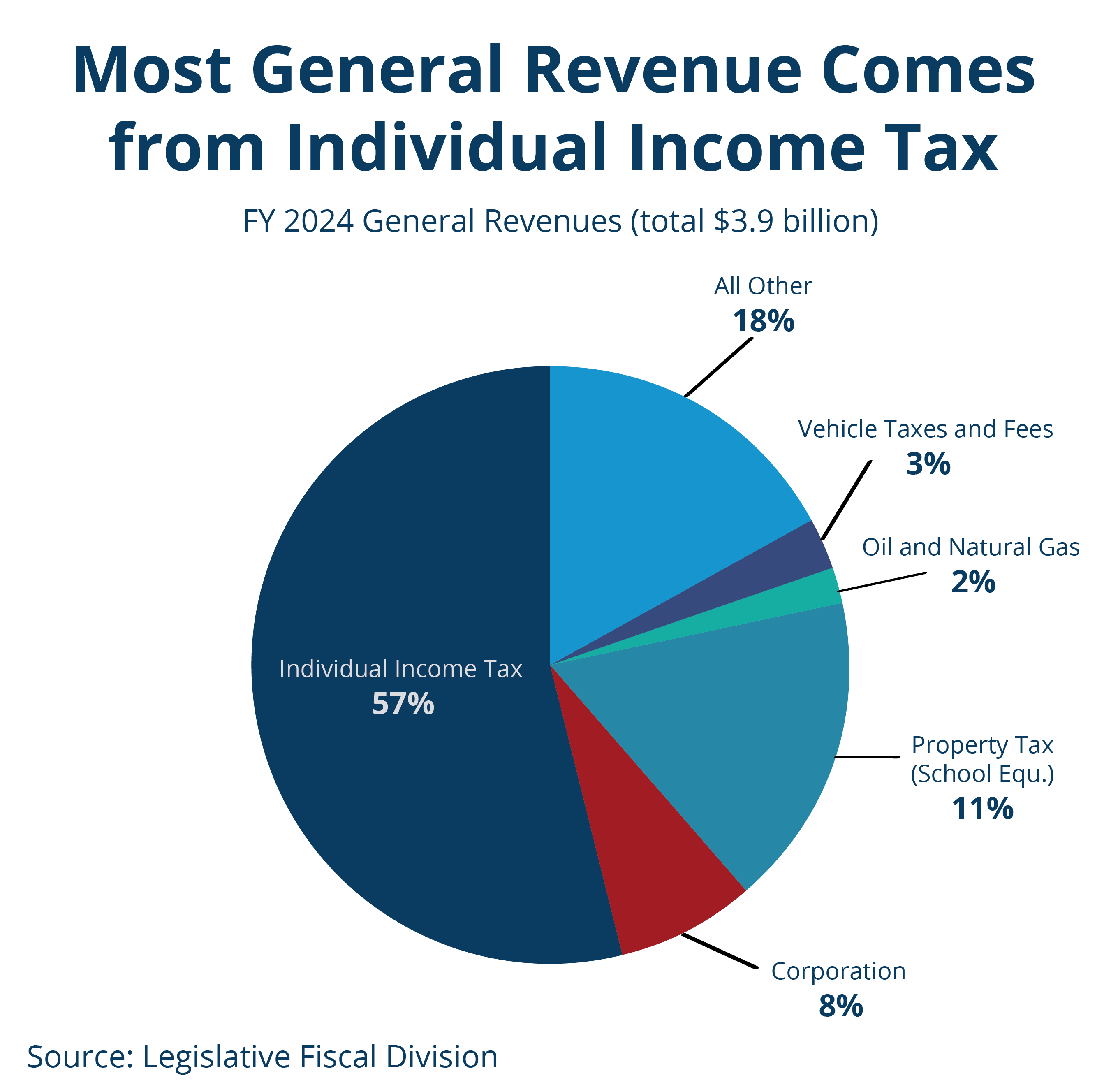

In Montana, these shared investments are managed mostly through the state’s General Fund. Taxes make up the vast majority of the revenue for the General Fund, and the individual income tax is the single largest source of revenue, comprising nearly 60 percent of the state’s General Fund revenue.[1] The 2023 Legislature moved revenue generated from the 95 statewide property tax mills and interest earned on treasury cash to special revenue accounts to be used for specific purposes, instead of into the General Fund. [2] As these revenue sources are quite large and change the makeup of the General Fund, the figure shown refers to general revenue. General revenue includes all revenue sources into the General Fund, property tax revenue from the 95 mills that flows to the state, and interest earned on treasury cash.

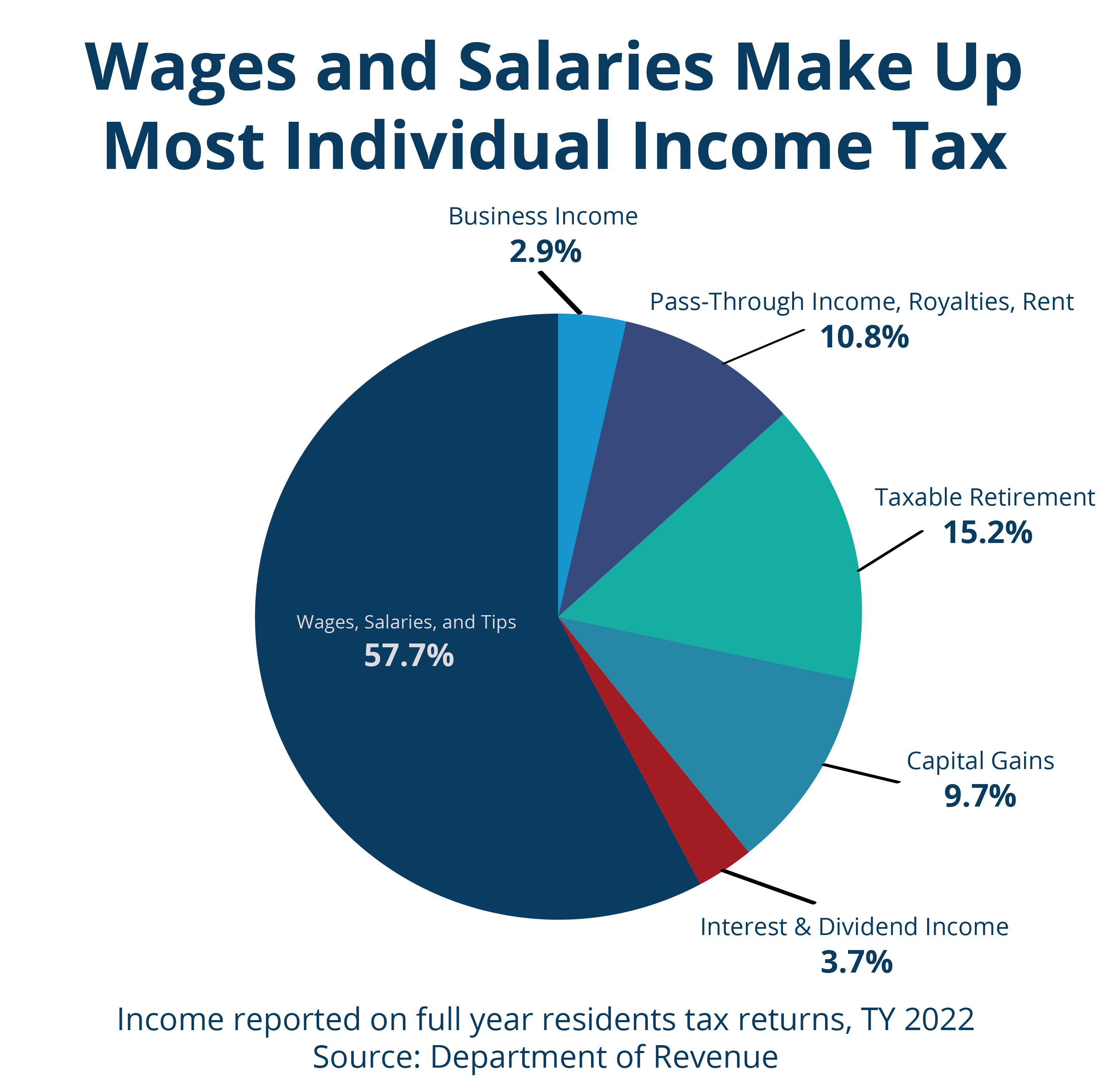

Wages and salaries make up more than half of income subject to individual income tax.[3] In general, taxes paid by corporations are paid through the corporate income tax. However, depending on how the entity is structured, business income may be reported through the individual income tax.

A C-corporation is a business structure where the corporation is taxed separately from the owners, and its taxes are classified as corporate income taxes. All  other businesses, including sole proprietorships, partnerships, limited liability corporations, and S-corporations, report income on individual returns, and this amount is reflected in both pass-through income and business income, which comprise less than 14 percent of total individual income.

other businesses, including sole proprietorships, partnerships, limited liability corporations, and S-corporations, report income on individual returns, and this amount is reflected in both pass-through income and business income, which comprise less than 14 percent of total individual income.

Past Income Tax Cuts Benefitted the Wealthiest

The last few decades in Montana have brought about great change to the tax system, and most of this change benefitted the wealthiest. The most significant piece of this change happened in 2003 when the Montana Legislature passed a bill that seriously altered the state tax system.[5] The changes made in 2003 included collapsing the income tax brackets and creating a tax credit for capital gains income. Both provisions resulted in a big tax cut for the wealthiest residents. These tax cuts cost the state nearly a billion dollars in revenue in the first decade following the change which could have been used to invest in Montanans through education, housing, and health care.[6]

Prior to the tax cuts implemented in 2003, Montana had 10 different income brackets, with each higher income bracket paying a slightly larger share of their income in taxes.[7] The state lowered the top income tax bracket from 11 percent to 6.9 percent.

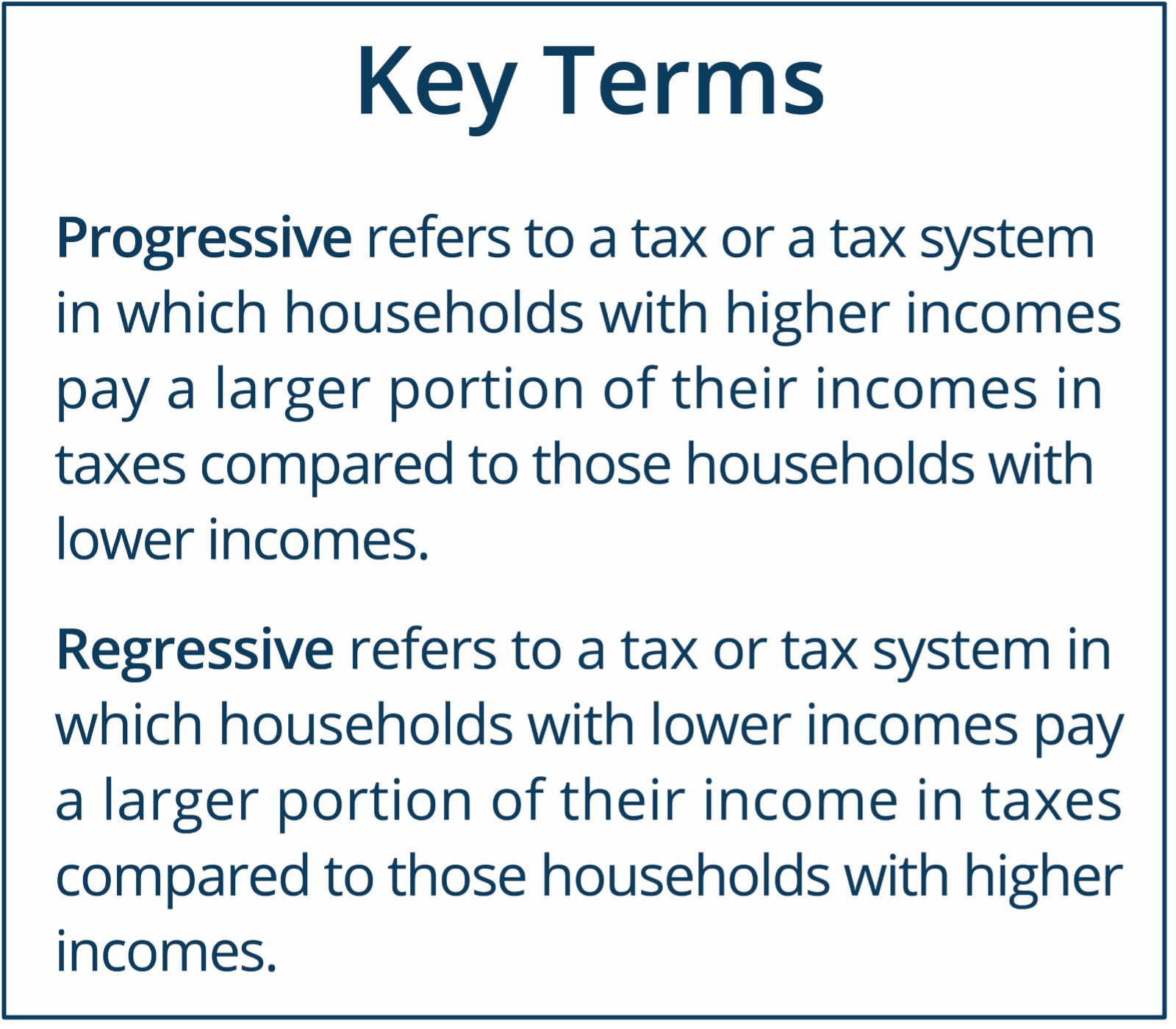

As a whole, these tax cuts have created a more regressive income tax structure. In fact, while our individual  income tax remains slightly progressive, it is not progressive enough to offset the regressivity of our property taxes and selective sales and excise taxes.[10] In other words, when looking at the entire tax system in Montana, taxpayers with lower wages pay a larger portion of their income in taxes compared to those with higher incomes. Regressive taxstructures, like Montana’s, contribute to growing income inequality.

income tax remains slightly progressive, it is not progressive enough to offset the regressivity of our property taxes and selective sales and excise taxes.[10] In other words, when looking at the entire tax system in Montana, taxpayers with lower wages pay a larger portion of their income in taxes compared to those with higher incomes. Regressive taxstructures, like Montana’s, contribute to growing income inequality.

For further information about the income tax bracket collapse, see Montana Budget & Policy Center’s report, The Montana We Could Be: Tax cuts, aimed at the rich, take a toll.

Capital Gains Tax Benefit Favors Wealth Over Work

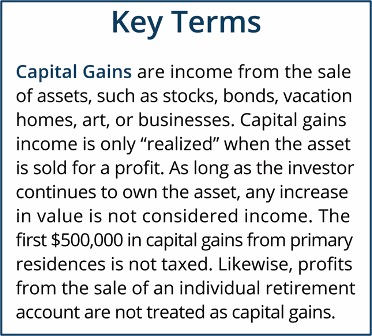

Currently, Montana is one of only nine states that gives significant tax breaks for capital gains.[11] Capital gains tax breaks cost the state millions of dollars and are unfair to Montanans who earn income through wages.

The 2003 Legislature passed a capital gains credit that lowered the effective tax rate for people who earn income through investments compared to those who earn income from wages.[12] The 2023 Legislature changed this tax credit to a lower tax rate for capital gains income.[13] Both policies create a tax system that favors wealth over work. In 2022, over 60 percent of the benefits from the credit went to the wealthiest one percent of taxpayers (just 5,031 households in Montana).[14]

Nearly all Montanans who earn lower and middle incomes do not benefit from capital gains tax benefits because they are much more likely to earn their  income on the job rather than through the sale of large assets. In 2022, 78 percent of Montana taxpayers – more than 470,000 taxpayers – did not receive any benefit from the capital gains credit.[15] In fact, the assets owned by most Montanans – primary residences and retirement funds – are not treated as capital gains income when they are sold.

income on the job rather than through the sale of large assets. In 2022, 78 percent of Montana taxpayers – more than 470,000 taxpayers – did not receive any benefit from the capital gains credit.[15] In fact, the assets owned by most Montanans – primary residences and retirement funds – are not treated as capital gains income when they are sold.

Treating capital gains more favorably than wages will not help the economy. In fact, the lost tax revenue could actually prevent growth by forcing state budget cuts. The capital gains credit cost Montana $89 million in 2022.[16] These vital dollars could have been used to fund growth-oriented services like education, health care, and infrastructure improvements.

Earned Income Tax Credit Makes Work Pay

In 2017, the Montana Legislature passed a state earned income tax credit (EITC), making Montana the 29th state to create a state EITC to help working families make ends meet.[17] Beginning in 2019, Montana started providing a refundable tax credit set at 3 percent of the federal EITC to households working at lower-wage jobs. The 2023 Montana legislature increased Montana’s EITC to 10 percent of the federal, beginning in tax year 2024.[18] In tax year 2022, 61,852 Montana households received the EITC.[19]

A state EITC is an effective tool to help people rise above poverty-level incomes by putting more money in the pockets of families to spend on groceries or catch up on bills. However, Montana can do more to improve the economic security of families living on low incomes by increasing the credit amount. Among the 30 states and District of Columbia that offer a state EITC, Montana’s 10 percent credit is among the lowest.[20] Raising the value of the credit to 25 percent of the federal credit would result in a maximum benefit of $1,958 and will go further in helping families meet the rising costs of their basic needs.[21]

Income Taxes in Indian Country

Generally, all individual Tribal citizens are subject to federal income taxes. The exception to this is income derived directly from allotted trust lands or treaty fishing rights.[22] In Montana, Tribal citizens are also subject to state income taxes if they live or work off the reservation where they are enrolled.[23] About 40 percent of American Indians reside off-reservation in Montana, and many more American Indians living on their reservation work in nearby communities.[24]

Federally recognized Tribal governments do not pay state income taxes because states do not have jurisdiction on Tribal sovereign nations.[25] Thus, federally recognized Tribal nations receive the same income tax exemption as federal and state governments. Income generated through Tribal corporations chartered under state law is subject to federal and state income taxation.[26]

Tribal governments, like federal and state governments, have the right to tax the income of their own citizens, but few, if any, actually do. One reason includes economic challenges, a part of the legacy of settler colonialism. Today, infringement upon Tribal sovereignty, systemic racism, and present-day discrimination play into a system of lower incomes and higher rates of unemployment on many reservations, contributing to the unfeasibility of taxing Tribal citizen income. In Montana, 14 to 37 percent of residents in each Tribal Nation live in households with poverty-level incomes.[27]

For more information, see MBPC’s Policy Basics on Taxation Authority in Indian Country.

Better Tax Choices for Montana

Our income tax system is one of the primary ways that we pool our resources to make investments in public services and infrastructure that help make our communities stronger, safer, healthier, and more prosperous. Montana can make better choices that do not put the greatest weight on those making the least. The following reforms would greatly strengthen Montana’s income tax system:

· Taxing capital gains income at the same rate as wage income;

· Restoring a top marginal bracket limited to highest-income households; and

· Increasing the value of the state EITC.

Montana needs a modern income tax system that makes continued investment in our communities and economy, paving the way for a more prosperous future for our children and grandchildren.

[1] Schaefer, S., “2024 FYE General Revenues,” Legislative Fiscal Division, accessed Sept. 3, 2024.

[2] Montana 68th Legislature, “An Act Generally Revising School Finance Laws,” HB 587, enacted on June 13, 2023.

[3] Department of Revenue, “Montana Individual Income Tax, Income Reported on Full-Year Residents’ Returns, TY 2022,” MBPC information request, received on Sept. 4, 2024, on file with author.

[4] Department of Revenue, “Montana Individual Income Tax, Income Reported on Full-Year Residents’ Returns, TY 2022,” MBPC information request, received on Sept. 4, 2024, on file with author.

[5] Montana 58th Legislature, “Income Tax Reduction with Revenue from Limited Sales Tax,” SB 407, enacted on Apr. 30, 2003.

[6] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “Montana Personal Income Tax Revenue Lost, 2005-2016,” Apr. 2016, on file with author. See also Montana Budget & Policy Center, “The Montana We Could Have Be: Tax cuts, aimed at the rich, take a toll,” July 2016.

[7] These brackets correspond to varying amounts of taxable income. Taxable income is income after deductions and exemptions have been subtracted.

[8] Montana Department of Revenue, “2019 Individual Income Tax Rates,” accessed Oct. 7, 2020.

[9] Department of Revenue, “Individual Income Tax Rates and Tables,” accessed Sept. 4, 2024.

[10] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in all 50 States, Montana: State and Local Taxes,” Jan. 2024.

[11] Only nine states provide a broad preferential tax treatment on capital gains. McNichol, E., “State Taxes on Capital Gains,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 15, 2021.

[12] Montana 58th Legislature, “Income Tax Reduction with Revenue from Limited Sales Tax,” SB 407, enacted on Apr. 30, 2003.

[13] Montana 68th Legislature, “An Act Revising the Tax Rates Applicable to Net Long-Term Capital Gains,” HB 221, enacted on Apr. 28, 2023.

[14] Department of Revenue, “Top 1% of Households, Total Income, Tax, and Capital Gains Income,” Sept. 2024, on file with author.

[15] Department of Revenue, “Income Reported on Full-Year Residents’ Returns,” Sept. 2024, on file with author.

[16] Department of Revenue, “Top 1% of Households, Total Income, Tax, and Capital Gains Income,” Sept. 2024, on file with author.

[17] Montana 65th Legislature, “Provide for Montana Earned Income Tax Credit,” HB 391, enacted on May 11, 2017.

[18] Montana 68th Legislature, “An Act Revising Individual Income Tax Laws,” SB 121, enacted on Apr. 28, 2023.

[19] Department of Revenue, “2022 EITC Filers,” Oct. 3, 2024, on file with author.

[20] Internal Revenue Service, “States and local governments with earned income tax credit,” accessed Oct. 2, 2024.

[21] MBPC calculations using Internal Revenue Service, “Earned Income Tax Credit Income Limits and Maximum Amounts,” Oct. 2024.

[22] Kim, Y., “Federal Taxation of Indian Tribes and Members,” Congressional Research, Apr. 8, 2010.

[23] Montana Legal Services Association, “Low Income Taxpayer Clinic: Tax Q&As for Indians,” Dec. 2016.

[24] Montana Office of Public Instruction, “Essential Understandings Regarding Montana Indians,” 2024.

[25] U.S. Constitution, Article 6, Clause 2; Oklahoma Tax Commission v. Chickasaw Nation, 515 U.S. 450, 458 (1995); Oklahoma Tax Commission v. Sac & Fox Nation, 508 U.S. 114, 126 (1993); Moe v. Confederated Salish & Kootenai Tribes, 425 U.S. 463, 475 (1976); Lummi Indian Tribe v. Whatcom County, 5 F.3d 1355, 1357 (9th Cir. 1993); Standing Rock Sioux Tribe v. Janklow, 103 F. Supp. 2d 1146, 1153-54 (D.S.D. 2000); Montana v. Blackfeet Tribe, 471 U. S. 759, 764 (1985).

[26] U.S. Internal Revenue Service, “Revenue Ruling 94-16.”

[27] U.S. Census, 2018-2022 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, “My Tribal Area,” for each reservation in Montana.

MBPC is a nonprofit organization focused on providing credible and timely research and analysis on budget, tax, and economic issues that impact low- and moderate-income Montana families.