State tax policy is not race-neutral. Decades of lawmaking by majority white decision-makers has resulted in a tax code that disproportionately benefits white, wealthy Montanans. This tax code, which asks more from Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) in Montana, contributes to the persistent racial wealth gap.

Montana’s tax code exacerbates the impacts of historical patterns of racism in Montana and the country by requiring people living on the lowest incomes, who are disproportionately Black, Indigenous, and people of color, to pay 22 percent more of every dollar in state and local taxes than the wealthiest.[1] This pattern is getting worse. During the last legislative session, Montana lawmakers passed tax cuts expected to cost upwards of $100 million over the next biennium that disproportionately benefit the wealthy. [2] These changes further entrench our tax code with laws in service of those who hold power over the rest of us. These laws include cuts to our top income tax rate, property tax cuts for owners of business equipmen t, and tax cuts for other special interests.

t, and tax cuts for other special interests.

To begin to undo a vast history of oppression and discrimination in Montana, we should make our tax code more equitable. Reinstating a top income tax bracket, repealing capital gains tax exemptions that give lower tax rates to income earned from wealth over wages, and eliminating property tax exemptions for big business are good places to start. Montana has a choice to make. Give Montana’s revenue away to the wealthiest and big business with sweetheart deals or begin to invest in communities to help all Montanans prosper. Helping to make housing, child care, education, and health care more affordable for all of us living and working in Montana today will bring about a brighter tomorrow.

Racial Wealth Gap

Income and wealth gaps across lines of race are a product of our country and state’s history of ongoing racist, biased, and discriminatory policies and practices against Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC). Income is money received for work, business profits, rent, etc. Wealth is savings accumulated over time that allows people to invest in the future, like attending higher education or purchasing a house. People can use their wealth to weather challenging times, such as if someone loses a job, and can even generate and create income for people through interest or dividends on stock.

The racial wealth gap in this country has roots in colonization, beginning with the kidnapping and forced enslavement of Black people and the stealing of land from Indigenous people. Our terrible beginnings have continued throughout the United States and individual state histories. As noted below, Montana is no exception. While some look to these policies as stories from the past, the truth is that the legacy of racism continues to exist in our tax code today, continuing this history that has kept BIPOC Montanans from growing wealth and participating in our economy on an even playing field.

Laundry Taxes Targeting Chinese Men

Chinese immigrants began running laundries in San Francisco around 1848, which quickly spread to other growing western mining towns, including those in Montana.[3] From the 1860s into the 1900s in the west, Chinese laundrymen faced great discrimination and violence, including discriminatory laws of excessive taxation and licensing fees. This came at a time when Chinese people were not allowed to be citizens of the United States or vote (in 1943, Congress granted Chinese people the right to become citizens).[4]

In 1869, Montana passed a laundry tax of 25 percent of gross earnings targeted at Chinese laundrymen.[3] The Montana Territory eventually stopped collecting this tax, possibly because of a court ruling. Then in 1895, after Chinese men had more success in the laundry business, Montana passed a license fee of $10 per quarter-year ($25 for laundry businesses with employees). This law exempted steam laundries and women-operated hand laundries, which white people owned. After being challenged unsuccessfully at state courts, the federal district court ruled the law unconstitutional. Then in 1908, Montana passed a $10 tax per quarter-year on laundries, again exempting steam and women-operated laundries. This case was challenged unsuccessfully at the Montana Supreme Court. Once evidence brought forward showed that the law applied to only Chinese men, the law was declared unconstitutional.

Great Falls Exclusion of Chinese People

Great Falls was incorporated in 1888 and from its inception, had a policy of total exclusion of Chinese people.[5],[6] Great Falls’ policy was not in a vacuum, as Congress had passed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 that prohibited the immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years and barred all Chinese immigrants from citizenship.[7] Great Falls’ first Chinese resident did not arrive until 1938.6

Segregation, Discrimination, and Exclusion of African Americans

During the 1920s, Great Falls was home to many Black residents.[6] They experienced pervasive segregation and discrimination and were prohibited from eating at restaurants and going to nightclubs that were not Black-owned. They were also disallowed from joining unions and thus excluded from higher-paying jobs in refineries and repair yards.

Great Falls was one piece of a broader system of discrimination and exclusion of Black residents in Montana, which resulted in the exodus of many. Helena, Montana had a population of 420 African Americans in 1910 (3.4 percent), down to 131 by 1930 and only 45 by 1970.[8] In the late 1890s and early 1900s, African Americans in Helena had an established middle-class community, in addition to laborers for the railroad and mines. Helena had Black newspapers, Black-owned businesses, and Black community groups. Shamefully, in 1906 public attitude shifted, as evidenced by Helena’s prosecuting attorney's statement, “It is time that the respectable white people of this community rise in their might and assert their rights.” The Helena newspaper supported this statement. Strict miscegenation laws followed, going into effect in 1907 and lasting into the 1950s, disallowing marriage across races.[9]

Taking of Land and Forced Assimilation of Indigenous People

Into the 1870s, Indigenous people in Montana survived on game and plants they harvested.[10] By 1880, the U.S. government killed hundreds of thousands of bison, a main food source, to aid in the westward expansion of settlers and to forcibly remove Indigenous people from their land.[11] Despite treaty agreements that required the U.S. government to compensate Indigenous people for their ceded land, Congress did not honor its legally binding treaty obligations and failed to provide enough food, killing many Blackfeet, Assiniboine, Gros Ventre, and Sioux during the “Starvation Winter” of 1883.[10] This event resulted in further land grabs and the forced assimilation of Indigenous people.

Racist History of Montana’s Tax System

Dovetailing off a history of racist policies and practices, the following legislative bills, constitutional initiatives, audit practices, and policies compile a select list of current policies affecting Montana laws and practices that disproportionately impact BIPOC Montanans. This list is by no means exhaustive but provides many examples of how and why policies continue our historical legacy of benefitting white people over BIPOC.

Many of these policies not only disproportionately hurt people of color in Montana but also disproportionately hurt Montanans living on lower and even middle incomes, regardless of race. The purpose of this report is to show that these policies, and likely many others, are currently disenfranchising many Montanans of color and other marginalized communities within Montana. Montana should not be a place where your race or ethnicity determines your income, wealth, profession, or any other factor. Montana’s tax code needs to change to move toward an equitable Montana.

Local government Property Tax Limitation Stems from Racist Limits on Education Funding

Some of the earliest state property tax limitations in the United States stem back to post-Reconstruction Alabama. These property tax limitations were designed to protect white property owners from tax increases to fund the expanded education of Black Americans.[12] During this period, Arkansas, Missouri, and Texas also adopted property tax limits that exist today. While Montana much more recently enacted property tax limitations, the concept of state property tax limitations stems from a desire to withhold resources from Black Americans at the expense of entire communities. With less property tax revenue, all school children see fewer school supplies, and all community members experience the same lower-quality infrastructure.

Today, Montana limits local governments from increasing their property tax levies for existing property to one-half of the rate of inflation averaged over the prior three years.[13] While there are some exceptions to this hard cap on property tax growth, the reality is that many communities lack the ability to maintain adequate government services. These limitations have a disproportionate impact on already marginalized communities.

Like the intention of property tax limitations passed in southern states, post-Reconstruction, Montana’s current limitation on property taxes results in a lack of local government revenue and a corresponding struggle for local governments to provide the infrastructure and other services that residents need.

Individual Income Tax Cuts Benefit the White and Wealthy

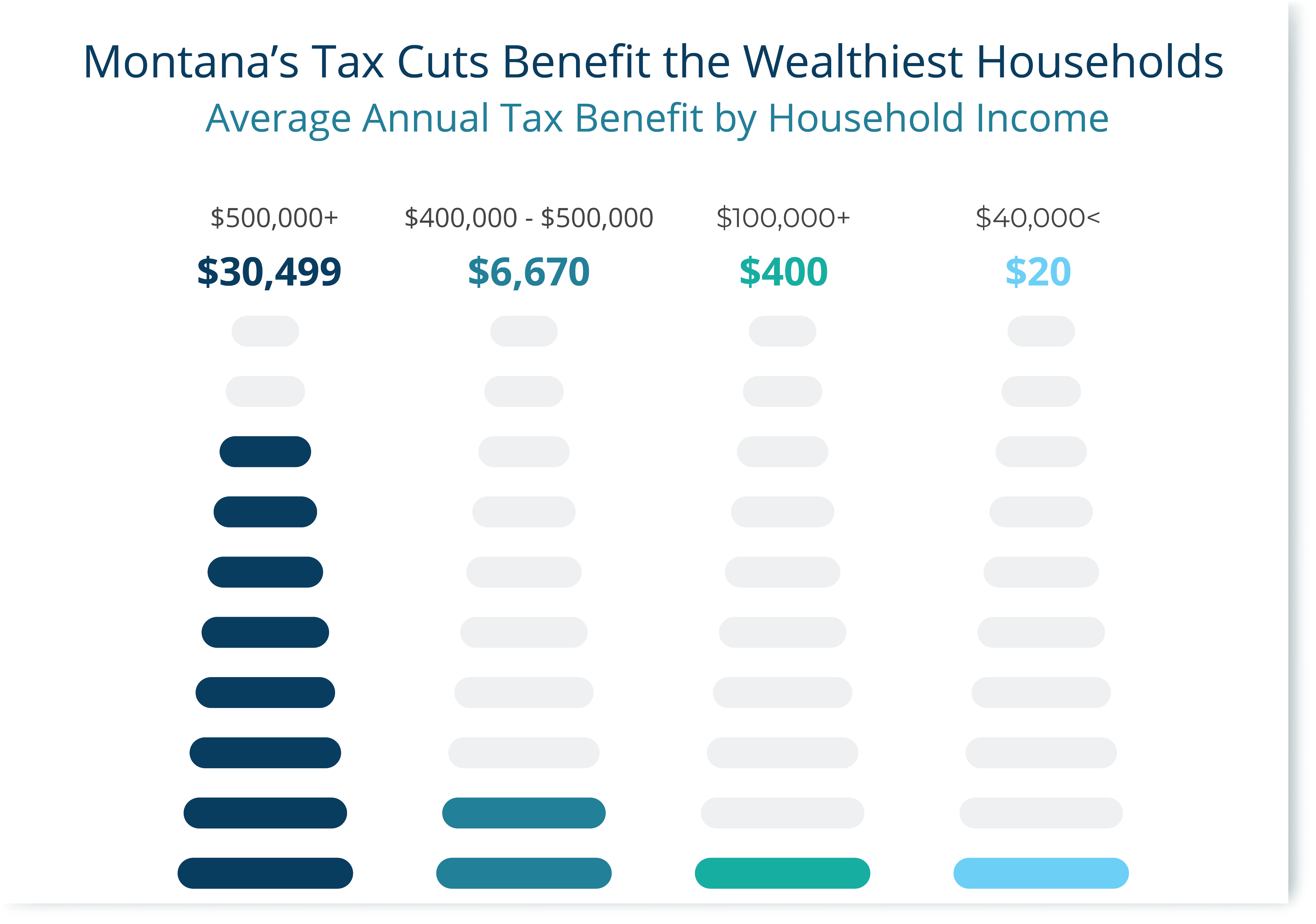

In 2003, the Montana Legislature passed a bill that considerately altered the state tax system by providing a significant cut for the wealthiest households, which are disproportionately white. The changes made in 2003 included collapsing the income tax brackets and creating a tax cut for capital gains income.[14] Both of these provisions made our tax system more regressive, giving a more significant tax cut to high-income households, and costing the state nearly a billion dollars in the decade that followed, which could have been used to invest in our future.[15] This bill provided much larger benefits for the wealthiest Montanans than everyone else. For example, Montanans with incomes over $500,000 received tax benefits in 2005 of $30,499 on average, and those tax benefits dropped with each income level.[16] Even those with incomes between $400,000 and $500,000 received substantially less, at an average tax cut of $6,670 annually. Going down further in income levels, you see those with incomes just over $100,000 had tax cuts of less than $400 annually, and those with incomes just over $40,000 annually received less than $20 on average.

This bill provided much larger benefits for the wealthiest Montanans than everyone else. For example, Montanans with incomes over $500,000 received tax benefits in 2005 of $30,499 on average, and those tax benefits dropped with each income level.[16] Even those with incomes between $400,000 and $500,000 received substantially less, at an average tax cut of $6,670 annually. Going down further in income levels, you see those with incomes just over $100,000 had tax cuts of less than $400 annually, and those with incomes just over $40,000 annually received less than $20 on average.

Today, the capital gains tax credit costs the state $64 million each year, and 90 percent of this benefit goes to the richest 20 percent of households.[17]

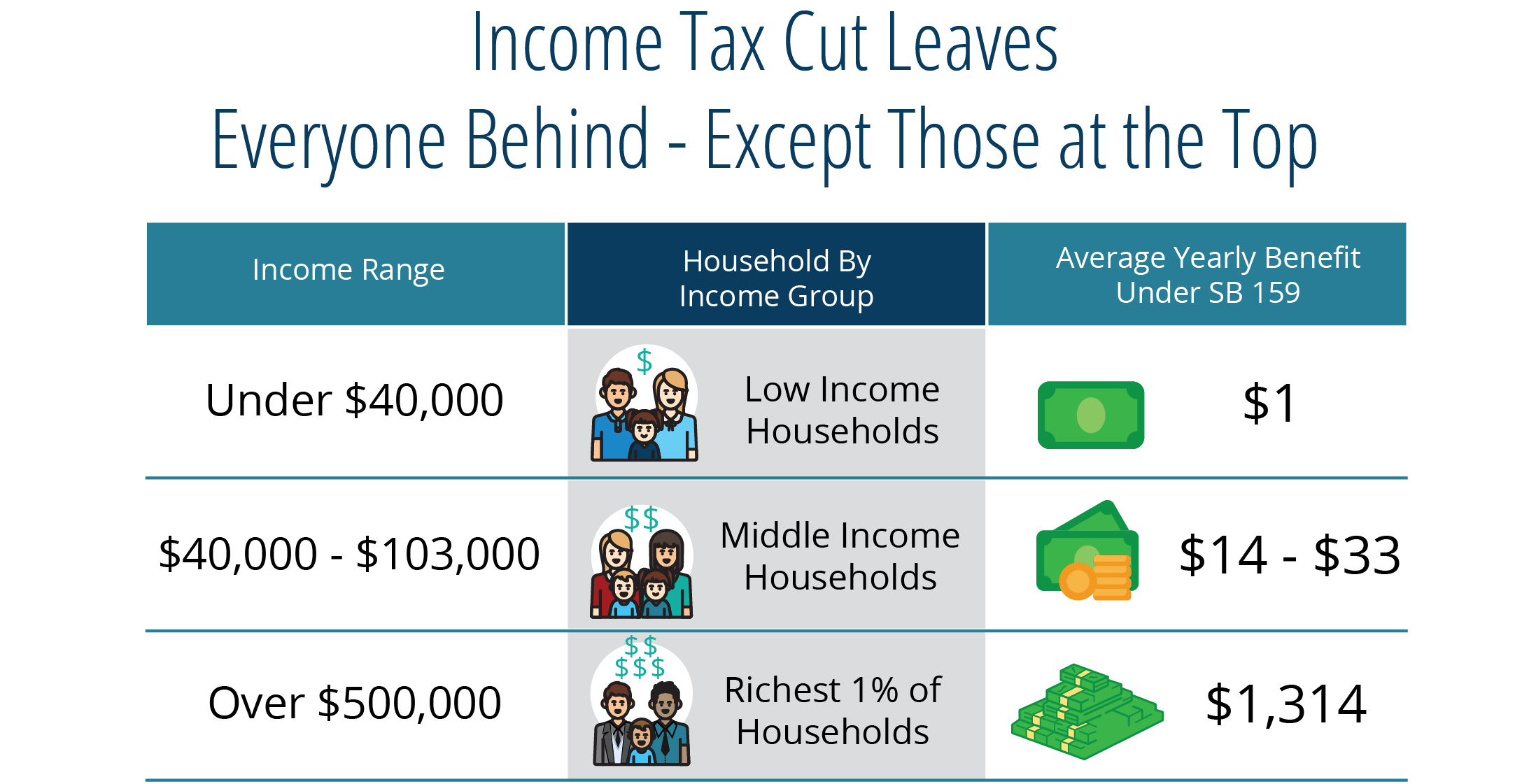

More recently, the 2021 Montana Legislature passed several bills that further cut the top individual income tax rate. The first to go into effect dropped the top tax rate from 6.9 percent to 6.75 percent.[18] Nearly 80 percent of the benefit of this tax cut goes to the wealthiest 20 percent of Montanans, and even starker, more than 96 percent of the tax cut goes to white Montanans. At the same time, Indigenous Montanans see only 0.9 percent, despite holding 1.9 percent of total returns.[19] Data limitations grouped all other individuals into an “other single race” category, making it difficult to know the impact on Black Montanans and other Montanans of color. This category received 3.6 percent of the total tax cut, despite holding 5.6 percent of total returns.

IRS Audits and Racial Bias

Between 2010 and 2017, the IRS enforcement budget dropped precipitously, forcing a reduction in the number of audits. This resulted in an excessive reduction in audits for taxpayers with an adjusted gross income of $500,000 or more (69 percent) and a much smaller audit rate decline for those who claim the earned income tax credit (36 percent).[20] The practices adopted at the time resulted in a shift to a higher reliance on audits from families with low incomes, as opposed to wealthy families. This practice is not only unfair, but it is also unwise in terms of expected gain. Even more egregious, these IRS audits disproportionately target families of color, continuing this country’s legacy of distrust and monitoring of citizens of color.

In the 10 most audited counties in the United States, 51 percent of people claimed the EITC, and 79 percent of the population is BIPOC.[20] In the 10 least audited counties in the United States, only about 10 percent of the people claimed the ETIC, and just 7 percent of the population is BIPOC. Current practices within the IRS have resulted in a racist system of tax auditing, and as the information gleaned from federal tax audits flows through to states, state audits follow the lead of these racist practices.

Mortgage Interest Deduction Benefits Whiteness and Wealth

The mortgage interest deduction was not initially created to promote homeownership. It was passed with the federal income tax in 1913, which allowed some business expenses to be deductible, including interest on loans.[25] Different types of loans were difficult to differentiate at the time, so interest on mortgages was also deductible. As 98 percent of households were exempt from the federal income tax at this time, the mortgage interest deduction only touched the very wealthy and continues to benefit higher-income households disproportionately.

US policies like the New Deal have helped white families, mostly headed by men, to grow wealth through homeownership while at the same time discouraging homeownership from BIPOC families.[21] These policies had their intended effect, and today, homeowners are disproportionately white, and thus, are more likely to benefit from the mortgage interest deduction.[22] Land status in Indian Country sometimes makes it more difficult for the land to be used as collateral for loans.[23]

Montana conforms to the federal mortgage interest deduction, which allows an itemized deduction for home mortgage interest paid during the tax year, costing the state $59 million in 2019.[24] At the national level, white households make up 66 percent of the population, but benefit from 71 percent of the mortgage interest deduction.[25] Over 62 percent of mortgage interest deduction tax benefits go to individuals with incomes over $200,000.[26]

If policymakers eliminated the mortgage interest deduction, half of the additional revenue in Montana would come from households with the highest 20 percent of income.[27] Effective state and local tax rates for households with the lowest 60 percent of incomes would not change, on average. Montana would have an additional $30 million annually in revenue that could help invest in our communities and improve our current inequitable system.

Elimination of the Estate and Inheritance Taxes Benefits Wealth

Household wealth offers financial security and allows for investments in the future, like higher education, home purchases, or saving for retirement. The racial wealth gap, or the difference in wealth by race, is staggering. Because of years of racist policies that have favored white people, Black families in 2019 held, on average, 13 percent of the net worth of white families.[28] As only the very wealthy pay estate and inheritance taxes, these wealth taxes can help address the racial wealth gap and fund investments in our communities.[29]

Prior to the year 2000, Montana collected around $18 million annually in estate and inheritance taxes.[30] Estate and inheritance taxes are two methods for taxing the transfer of wealth after death. An estate tax is a tax on the value of an estate when a person dies, paid by the deceased.[24] An inheritance tax is paid by each heir on the amount received from an estate. Montana’s inheritance tax was repealed in November 2000. Montana’s estate tax, however, held on a bit longer as it was based on the federal estate tax’s credit for state taxes. Beginning in 2005, federal law changes phased out the credit for state taxes, effectively removing Montana’s estate tax. Prior to the elimination of state inheritance and estate taxes, Montana received only 800 to 900 inheritance tax returns with inheritance or estate tax due each year due to the very high-income thresholds.[31] This tells us that estate and inheritance taxes raised state revenue from the wealthiest Montanans, who are disproportionately white, before its elimination.

Wealth transfer taxes like estate and inheritance taxes are tools to help reduce the racial wealth gap and fund equitable schools, access to health care and higher education, and other tools to help make Montana a better place to live and raise families. Montana should consider re-enacting and reworking our estate tax like many other states did after the federal changes in 2005.[29]

Constitutional Prohibition of Property Transfer Taxes Helps the Rich

Another way of taxing wealth is through property transfer taxes or fees. Thirty-five states have these types of taxes, and 7 of those states levy a surcharge on only the highest-value homes or have a progressive bracket structure, meaning higher-value homes get taxed at higher rates.[32]

In 2010, Montana passed CI-105, which prevented any tax on the sale or transfer of property in the state.[33] This policy has prevented Montana from even considering a tax on the transfer of wealth through high-value property, which is one way to reduce the omnipresent racial wealth gap. A wealth tax like this would not only help to improve the fairness of our current tax system, which taxes those living on the least more than the wealthiest Montanans, it would also provide needed revenue to invest in our communities and help provide services like access to higher education, healthy food, housing supports, and more.

Property Tax Shifts to Residential Property Benefits Whiteness and Wealth

Over the last few decades, the Montana Legislature has enacted many property tax cuts that have resulted in an overall shift from business property to residential and other types of property. Property tax at the local level is a zero-sum game, meaning that as legislative decisions to exempt or reduce tax rates for some types of property are passed, other types of property make up the lost taxes. Today, residential property taxes make up more than 50 percent of all property taxes in Montana, compared to 30 percent in 1993. [24],[34]

Tax exemptions that have arisen over the years contributing to the increased reliance on residential property include tax exemptions like the intangible personal property exemption and tax rate reductions and exemptions on business equipment property. In 1999, the Legislature changed the law to exempt certain components of the value of a business in calculated property taxes. Policymakers expanded the law to include larger businesses, including large telecommunications and utility companies. The impact of this policy has resulted in a significant reduction in property taxes for larger companies. In 2020, large companies benefitted from tax reductions of over $96 million from this exemption, over $80 million of which was shifted to other types of property.[24]

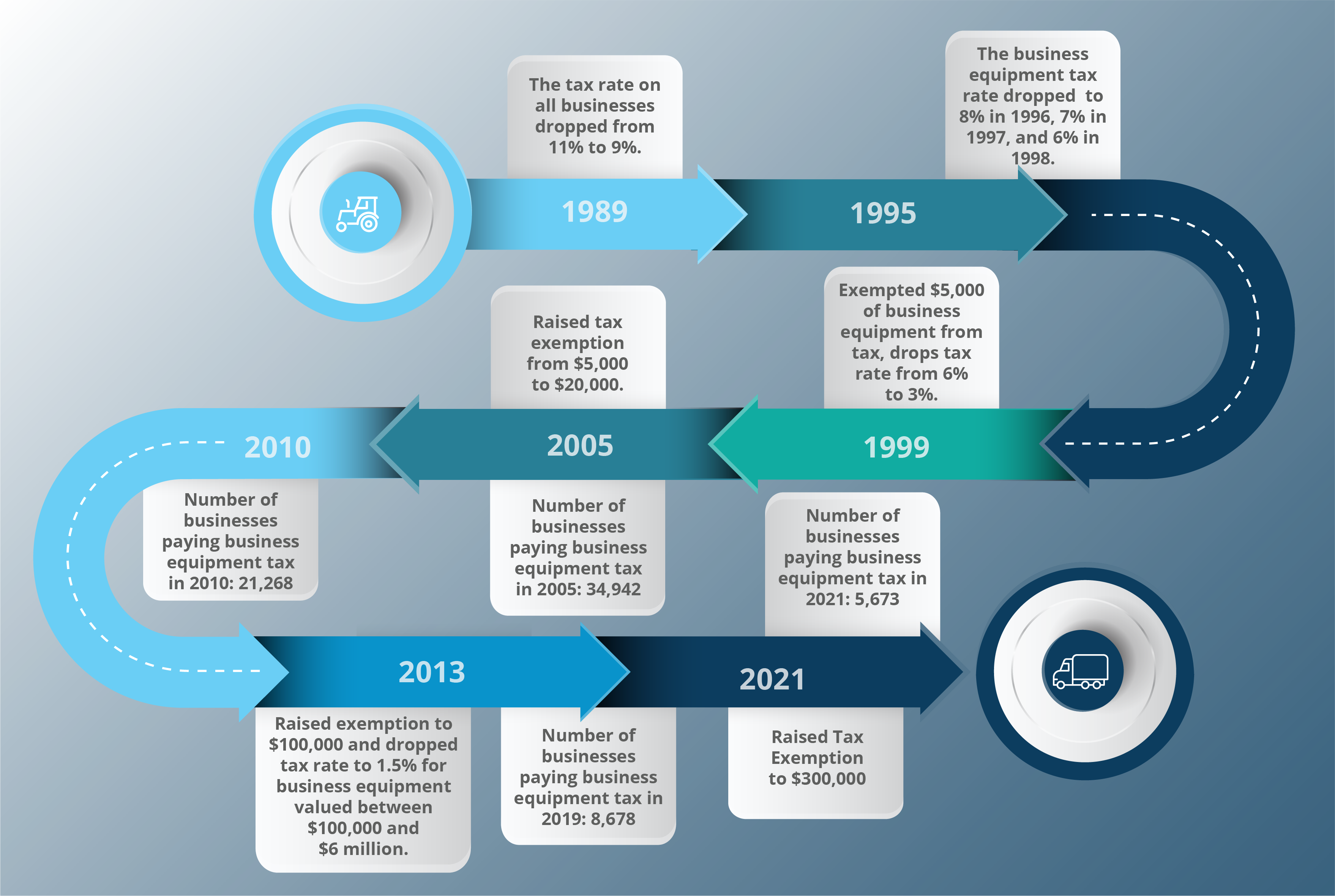

Business equipment is one class of property that has benefitted from tax reductions numerous times in the past few decades. From 1989 to 2021, the Montana Legislature has cut business equipment taxes eight times through reductions in rates and expanded exemptions. Today, the first $300,000 of business equipment is not taxed, business equipment valued between $300,000 and $6 million is taxed at 1.5 percent, and business equipment in excess of $6 million is taxed at just 3 percent.[35] These increasing exemptions have reduced the number of businesses paying business equipment tax from over 18,000 businesses in 2008 to 5,673 in 2021. There were likely many more before the first exemption was passed in 1999.[36] In addition, while property tax is by nature a regressive tax, these tax exemptions and rate reductions for business property exacerbate that regressivity, asking residential property taxpayers to pay more while owners of business property pay less. Some of these specific proposals may not have immediately increased the reliance on residential property because they were coupled with laws requiring state funding to backfill local government budgets. However, they increased the property tax system's reliance on residential property over time and shifted tax responsibility away from business owners and to general fund contributions, much of which is made up of revenue from individual people through individual income tax.

In addition, while property tax is by nature a regressive tax, these tax exemptions and rate reductions for business property exacerbate that regressivity, asking residential property taxpayers to pay more while owners of business property pay less. Some of these specific proposals may not have immediately increased the reliance on residential property because they were coupled with laws requiring state funding to backfill local government budgets. However, they increased the property tax system's reliance on residential property over time and shifted tax responsibility away from business owners and to general fund contributions, much of which is made up of revenue from individual people through individual income tax.

Public and Private School Tax Credits Preferentially Help White Students

Our strong public school system provides opportunities for children across the state and helps create a well-educated workforce. Public and private school tax credits do not enhance our public education system. Instead, they divert funding from an equitable distribution to public schools, are expensive, and ultimately harm students and communities. These tax credits reduce the Legislature’s ability to find state-based solutions for improving our education system and make it more difficult for our public schools to provide quality education to the wider community.

The 2015 Montana Legislature passed the qualified education tax credit for contributions to student scholarship organizations and the innovative educational public school tax credit.[37] The 2021 Legislature drastically increased the effect of these private and public school tax credits by increasing the maximum credit amount from $150 per taxpayer to $200,000.[38]

Over two-thirds ($694,000) of the innovative educational public school tax credit went to Big Sky K-12 school district. Only 23 taxpayers in Montana benefitted from the $1 million loss in state revenue from this credit.[39] Eighty-seven percent of Big Sky K-12 students are white, compared to 78 percent of all Montana K-12 students, and household incomes in Big Sky are higher than average.[40],[41],[42] This creates inequities in school funding across the state, as the school district receiving the large majority of funds designated for innovative educational programs are disproportionately white.

Student scholarship organization donation tax credits provide tax incentives for private education, which reduce the Legislature’s ability to find state-based solutions for improving our education system and make it more difficult for our public schools to provide quality education to the wider community. Private school options do not exist for many rural students and most American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) students.[43],[44] Across the country, 84 percent of school districts with AI/AN enrollment of at least 25 percent have only public schools available. In Montana, 94 percent of school districts with at least 25 percent of AI/AN enrollment have no private school options.[45]

Racist History Behind Sales Taxes

While Montana does not have a general statewide sales tax, past proposals sought to pass a statewide sales tax in exchange for reductions of other tax types.[46] Sales taxes are regressive, meaning that families living on lower incomes, who are disproportionately families of color because of past and ongoing policy choices, pay a larger share of their incomes in sales taxes than wealthier, often white families.

Statewide sales taxes have a racist history. Mississippi adopted the first sales tax in 1932 to reduce property taxes and shift tax responsibility from property owners to consumers.[47] This effectively reduced the taxes owed mostly by white property owners and increased taxes owed by Black households that owned little to no property.

There are ways to mitigate the regressivity of sales taxes, most notably refundable sales tax credits, which provide an income tax credit for taxpayers below certain income levels. Refundable sales tax credits are essential to any good sales tax proposal.

Continual Refusal of State Legislature to Raise Revenue

Raising sufficient revenue by closing tax loopholes and ensuring the wealthiest are paying their fair share is critical to funding high-quality schools in all communities, infrastructure, access to health care, and other programs that are targeted to help overcome racial and ethnic inequities. These investments would help build an economy where benefits are more widely shared. In recent decades, six out of seven major tax reform bills that passed have decreased state revenue.[48] Targeted action today can address inequities created by the past, but only if the state has sufficient revenue to address past harms.

Policy Proposals to Advance an Anti-Racist State Tax Code

There are many options for policymakers to advance an anti-racist state tax code. Montana should reinstate a top income tax bracket on incomes in excess of $250,000. Montana should repeal many racist tax exemptions and credits throughout the tax code, including the school contribution credits, the capital gains tax break, and the mortgage interest deduction, tax breaks that continue to help those with wealth who are disproportionately white. Proceeds from the repeal of the mortgage interest deduction should be reinvested in a housing trust fund that targets housing supports to BIPOC Montanans who are disproportionately struggling in our difficult housing market.

Other proactive solutions Montana can pursue that would help make our tax code less regressive, and more anti-racist include increasing our state earned income tax credit, creating a state child tax credit (CTC), reinstating an estate tax on the transfer of wealth above certain levels, and increasing the inflation factor used to calculate local government budgeting authority. When the federal CTC funded by the American Rescue Plan Act was in effect, 45 percent of Montana kids and 55 percent of Montana kids of color were lifted out of poverty.[49] If we continued this kind of investment through generations, kids would do better in school, complete higher education, and find themselves better prepared for the workforce. That’s the kind of investment Montana policymakers should be making now.

Lastly, collecting and publishing tax statistics by race, whether at the state or federal level, would strengthen our understanding of the effects of our tax system across race. Policymakers need data to make good decisions on how funding should be collected and allocated.

[1] Montana Budget & Policy Center, “Who Pays,” Jan. 14, 2019.

[2] Bender, R., “End of Session Tax Bill Round-Up,” Montana Budget & Policy Center, June 11, 2021.

[3] Bernstein, D., “Lochner, Parity, and the Chinese Laundry Cases,” William & Mary Law Review, Dec. 1999.

[4] The Bancroft Library, “Timeline of Chinese Immigration to the United States,” accessed Sept. 20, 2022.

[5] Montana Historical Society, “Montana: Stories of the Land, Chapter 14 – Towns Have Lives, Too, 1870-1920,” accessed Sept. 20, 2022.

[6] Robison, K., “Great Falls, Montana’s African American Nightclub,” Montana the Magazine of Western History, 2012.

[7] Lee, Erika. “The Chinese Exclusion Example: Race, Immigration, and American Gatekeeping, 1882-1924.” Journal of American Ethnic History 21, no. 3, 2002.

[8] Rothstein, R., “The Color of Law,” Liveright, 2017.

[9] Wood, A., “After the West Was Won,” Montana the Magazine of Western History, 2016.

[10] Montana Historical Society, “Montana: Stories of the Land, Chapter 11 – The Early Reservation Years, 1880-1920,” accessed Sept. 20, 2022.

[11] National Park Service, “History of Bison Management,” accessed Sept. 20, 2022.

[12] Leachman, M. et al, “Advancing Racial Equity with State Tax Policy,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Nov. 15, 2018.

[13] Mont. Code Ann., 15-10-420.

[14] Montana 58th Legislature, “Income tax reductions with revenue from limited sales tax,” SB 407, enacted on April 30, 2003.

[15] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “Montana Personal Income Tax Revenue Lost, 2005-2016,” MBPC information request, on file with author.

[16] Dodds, D., “The Revenue and Taxpayer Impacts of the Income Tax Provisions of SB 407,” Montana Department of Revenue, Dec. 2006.

[17] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy “Capital Gains model,” MBPC information request, received on July 27, 2022, on file with author.

[18] Montana 67th Legislature, “Personal Income Tax Relief Act,” SB 159, enacted on May 12, 2021.

[19] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “MT model SB 159,” MBPC information request, received on July 6, 2021, on file with author.

[20] Bloomquist, K., “Regional Bias in IRS Audit Selection,” Tax Notes, Mar. 19, 2019.

[21] Aibinder, S. et al., “The Roots of Discriminatory Housing Policy: Moving Toward Gender Justice in Our Economy,” National Women’s Law Center, Aug. 2022.

[22] National Equity Atlas, “Homeownership in Montana,” 2019.

[23] Center for Indian Country Development, “Tribal Leaders Handbook on Homeownership,” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, 2018.

[24] Montana Department of Revenue, “Biennial Report July 1, 2018 – June 30, 2020,” Dec. 15, 2020.

[25] Meschede, T., et al., “Misdirected Housing Supports: Why the Mortgage Interest Deduction Unjustly Subsidizes High-Income Households and Expands Racial Disparities,” National Low Income Housing Coalition and The Heller School for Social Policy and Management, May 2021.

[26] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2020-2024,” Nov. 5, 2020.

[27] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “Mortgage Interest Deduction Model,” MBPC information request, received on July 27, 2022, on file with author.

[28] Survey of Consumer Finances, Net worth by race or ethnicity, 1989-2019, accessed May 4, 2022.

[29] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “State Estate and Inheritance Taxes,” Dec. 21, 2016.

[30] Johnson, C., “Voters to Decide Fate of Inheritance Tax,” Missoulian, July 25, 2000.

[31] Montana 56th Legislature, “Minutes from Select Committee on Taxation,” May 11, 2000.

[32] Leachman, M. and Waxman, S., “State ‘Mansion Taxes’ on Very Expensive Homes,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Oct. 1, 2019.

[33] Mont. Const., Article VIII, Part VIII.

[34] Caplis, E., “Historic Property Taxes by Class,” Montana Department of Revenue, Nov. 28, 2016, on file with author.

[35] Mont. Code Ann., 15-6-138.

[36] Cole, D., “Centrally Assessed Taxpayers,” Montana Department of Revenue, May 12, 2022, on file with author.

[37] Montana 64th Legislature, “Provide for tax credits for contributions to public and private schools,” SB 410, enacted on May 8, 2015.

[38] Montana 67th Legislature, “Revise laws related to tax credit scholarship and innovative education programs,” HB 279, enacted on May 12, 2021.

[39] Zammit, T., “Department of Revenue’s HB 279 Donations Portal,” Montana Department of Revenue, Jan. 7. 2022.

[40] Office of Public Instruction, “Race/ethnicity and enrollment by school district,”, MBPC information request, received on May 25, 2022, on file with author.

[41] Office of Public Instruction, “Gems Data,” accessed May 25, 2022.

[42] U.S. Census Bureau, “Income in the Past 12 Months, 2013-2017 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table S1901,” accessed on Sept. 13, 2022.

[43] The vast majority of private schools are located in counties with metropolitan areas – Cascade, Flathead, Gallatin, Lewis and Clark, Missoula, Silver Bow, and Yellowstone. National Center for Education Statistics, “Search for Private Schools,” Dec. 7, 2020.

[44] U.S. Government Accountability Office, “Public School Choice: Limited Options for Many American Indian and Alaska Native Students,” Jan. 2019.

[45] O’Loughlin, H., “Tuition Tax Credits: A Threat to Montana-Based Education Solutions,” Montana Budget & Policy Center, Feb. 2021.

[46] White, K., “Generally revise taxes and the distribution of revenue through sales tax,” HB 300, Montana 66th Legislature, as introduced on Jan. 23, 2019.

[47] Leachman, M., et al, “Advancing Racial Equity with State Tax Policy,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Nov. 15, 2018.

[48] Bender, R., “Tax Overhauls in the Last Two Decades,” Montana Budget & Policy Center, June 25, 2019.

[49] Semmens, J., “What Would Help Families Make Ends Meet? Make the Child Tax Credit Permanent,” Montana Budget & Policy Center, Sept. 14, 2019.

MBPC is a nonprofit organization focused on providing credible and timely research and analysis on budget, tax, and economic issues that impact low- and moderate-income Montana families.